David Myers stood before his Tokyo classroom, and initially ignored the rumble underneath his feet. He kept writing on the board, assuming it was merely the next tremor to shake a nation where minor earthquakes are frequent, and figuring it would soon pass.

When it didn’t, and the shaking lingered longer than usual, the teacher took notice. He stopped writing on the board. He wasn’t yet overly concerned, but the rattling was significant enough that one student asked if she could get under her desk, for safety’s sake.

“I thought that was a little melodramatic,” Myers said. “But sure. If you want.”

It was then the shaking changed. Small tremors began grouping together, causing the building to sway. He had never felt anything like it during his five years of living in Japan – and, as it turned out, neither had natives who’d lived in the country all their lives. Even some 231 miles southwest of its epicenter, Myers, a Boston University online art education student, was feeling the effects of what proved to be one of the most powerful earthquakes to strike the nation in centuries.

“Five seconds after the first student went under her desk,” he said, “I was telling everyone to do the same.”

At the Canadian school where Myers teaches, the damage was small. Plaster art fell off the wall of his classroom. A drink spilled. Books tumbled off the shelves. The power stayed on, but cell phone service went out, so as word arrived that a tsunami was making landfall in other parts of the country, Myers was left pressing redial every couple of minutes in a desperate attempt to reach his wife. She was eight months pregnant with twin boys and was staying with her parents in Chiba. Myers wasn’t sure how close that city was to the coast, but his fears were growing.

Eventually he learned that his family was safe. His students learned the same of their own loved ones, and although he and most of the school spent the night camped out in the gym because the train system needed to be inspected, they were largely unscathed.

Of course, other parts of the country could hardly say the same.

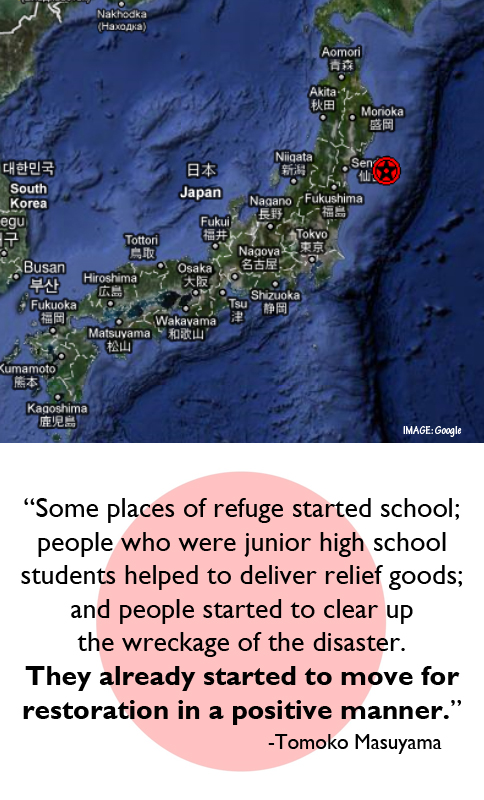

This excerpt was taken from a note written by Tomoko Masuyama, a BU Online criminal justice student who was born, raised, and still lives in Japan. To read the full text of the note, click on the image above.

The earthquake and subsequent tsunami so hammered the nation that officials have estimated the damage at a cost of 25 trillion yen – which equates to $309 billion, or four times as expensive as the destruction left by Hurricane Katrina – and death tolls were still climbing toward 10,000 as the search for missing bodies continued almost two weeks later.

Yet among the things that have most impressed Myers amid the tragedy has been the ability of Japan, and its people, to cope with disaster.

“I am certain not even the worst would change how Japanese people behave toward each other,” he wrote nine days after the earthquake, explaining that part of the reason he loves the country is because of how orderly and safe it is.

“Even in the tsunami shelters people are still sorting their garbage for recycling. Everywhere else is mostly normal. Businesses are running. Trash is still collected. Construction and road work has resumed. Aside from scheduled blackouts, things seem back to normal.”

Where he is located, Myers said people aren’t sure when the blackouts will end, but they “accept it easily now as inconvenient but necessary.” He said most have accepted the energy rationing without complaint, and he hopes that soon the media’s coverage of the catastrophe will begin to focus on how well the Japanese have dealt with the difficult circumstances and duress.

“Grocery stores manage demand and keep people from hoarding. Prices stay the same. People patiently wait in five hour lines for 20 liters of gas,” he said. “Gas and food are not in short supply; it is simply because when the train system is affected, traffic is more congested. It is an issue of transport within Tokyo – not supply. Stores are all open.

“Normalcy is something they want to get as soon as they can.”

Myers said that while the “vast, vast majority” of people are concerned about the Fukushima nuclear plant, where reactors were damaged as a result of the tsunami, and which faced the possibility of a meltdown, “no one is panicking.” Along with the Japanese, he says he has personally accepted the NHK broadcast service’s descriptions and explanations of what is happening at the power plants – and it’s only when watching Western coverage that he becomes worried.

He’s hoping that the coverage will soon change, however. It may be a long time before the cleanup is complete, and the threat isn’t gone even as electricity is restored to the nuclear reactors. But in the meanwhile Myers would like to see the media do a better job of telling the world about the cooperation, the behavior, and the persistent regard for each other that he’s seen in Tokyo. And across the country.

“Never expected such a thing in such a huge city,” he said.

* * * * *

On March 14, Boston University President Robert A. Brown reported that the members of the BU community in Japan are safe, including students in the study abroad programs in Kyoto and Tokyo, employees at the school’s liaison office in Tokyo, and faculty traveling in Japan. He also announced that the University had established a website listing agencies that are providing help to those impacted by the disaster. That site is found here.