By: Katherine Gianni

Dr. Houman Sarshar’s passion for promoting the art, culture, and history of Iran is well in evidence. It leaps off the pages of the books and articles he’s written, the volumes he’s co-edited, and it is embedded in the Kimia Foundation, an independent humanities organization that Dr. Sarshar founded and continues to oversee.

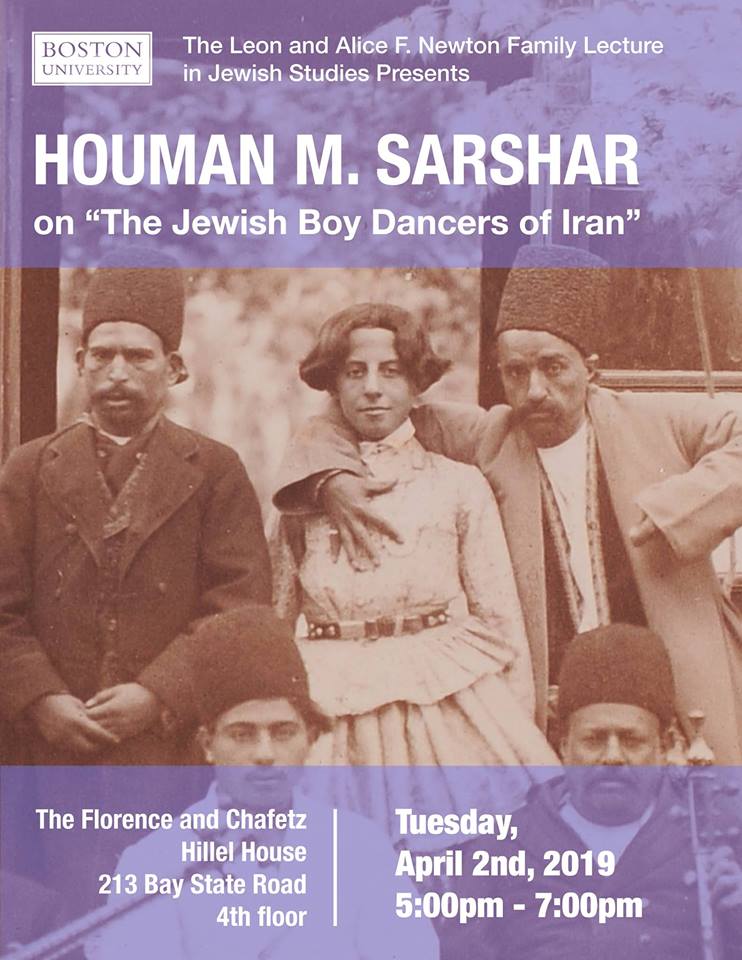

On Tuesday, April 2, Dr. Sarshar shared his zeal for the subject with the Boston University community in a lecture on The Jewish Boy Dancers of Iran. His presentation came as part of the Leon and Alice F. Newton Family Lecture in Jewish Studies, an event co-sponsored by The Elie Wiesel Center for Jewish Studies and the Boston University Center for the Humanities.

“Over the years, thanks to this series, we’ve been able to invite preeminent scholars in all areas of Jewish studies to BU,” said Associate Professor of Hebrew, German, and Comparative Literature Abigail Gillman in her welcoming remarks.

The lecture was established almost 30 years ago by the children of Leon and Alice F. Newton as a way to honor both their father, an alum of what was then called the BU School of Management, and their mother. Past speakers have included scholar Susannah Heschel, theologian Arthur Green, and philosopher Hilary Putnam, among others.

“Dr. Houman Sarshar did his undergraduate work in French and English literature at UCLA and his PhD in comparative literature at Columbia University. He’s a scholar, perhaps my favorite kind of scholar,” Associate Dean of the Faculty/Humanities Karl Kirchwey said, a grin spreading across his face. “One without a university affiliation.”

In his independent study of boy dancer entertainment in Iran, Dr. Sarshar has complied enough research to fill the pages of an entire encyclopedia. Through in-person interviews, thorough analysis of Qajar photography, and countless hours of fact-checking, he has laid the groundwork to learn more about the prevalence of such boy dancers in the past and their eventual disappearance from Iranian culture.

Prior to beginning his presentation, Dr. Sarshar issued a warning to the audience of students and community members gathered in the Florence and Chafetz Hillel House.

“The culture of dancing boy entertainment in Afghanistan has shed much necessary light on the despicable dynamics of enslavement, human trafficking, and sex slavery that today forms the backbone of this heart-wrenching hidden world,” he said. “While many of the features of the dancing boy entertainment of today’s Afghanistan are without doubt remnants of the same long tradition in neighboring Iran in particular, and the entire Persian world in general, there is at the very least one material distinction between what happens in twenty-first century Kabul and what occurred in pre-constitutional Iran. And that difference is time.”

Dr. Sarshar expressed that he was not referring to time in its chronological sense, but rather, “in the fullest sense of zeitgeist as the defining spirit or mood of a particular period of history as shown by the ideas and beliefs of the time.” By examining these dancers, he relayed that he did not wish to coat the realities of the boys’ humiliating position with a sense of nostalgia, but rather, use the images, texts, and testimonies as a means to broaden our understanding of the culture.

In telling the stories of the boy dancers, some of whom began their careers as early as six-years-old, Dr. Sarshar explained the ties between the profession and male homosexuality in Iran. While the dancers dressed in predominantly female clothing, he noted there was no mistaking the allure of their male gender identity. As various photographs and poems flashed across the screen, Dr. Sarshar argued that, despite legal strictures, Iranians widely engaged in homosexual relationships.

“Even occasional bans issued on male homosexual behavior throughout Iranian history had little impact on the love and desire of men over the years,” he said. “If anything, the fact that such bans had to be issued with any degree of frequency suggests that amorous and erotic relationships between men did not just occur in palaces, but throughout the general population.”

Dr. Sarshar concluded that the cultural norms surrounding homoeroticism, specifically when it came to dancing boy entertainment, shifted as Westerners categorized the practice as perverse, rather than something to be celebrated. The resulting shame led to the gradual disappearance of boy dancers. But, Dr. Sarshar, emphasized, there is still so much one can learn from this complicated history.

“The history of boy dancer entertainment in Iran is a rich one, not only in its scope and breadth, but more importantly in its unique capacity to provide a telescope with which to explore many dynamic nuances within Iranian society, culture, and even art history over the past 500 years,” Dr. Sarshar said. “My research therefore celebrates boy dancers and the culture of boy dancer entertainment precisely for the unprecedented analytic opportunities that the history of this tradition provides.”

To learn more about the Leon and Alice F. Newton Family Lecture in Jewish Studies visit https://www.bu.edu/jewishstudies/calendar/annual-lecture-series/.