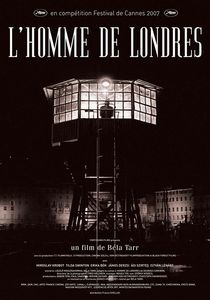

Bela Tarr is my favorite filmmaker, and The Man From London, coming soon to the MFA, is only his third film in the last twenty years. The last two, 1994’s Satantango and 2000’s The Werckmeister Harmonies are my favorite films of their respective decades, and the later is also simply my favorite film. Unless some kind soul decides to do a much-needed retrospective of his work, this will, in all likelihood be the only review of one of his films I write for this site. He has another film in production at the moment called The Turin Horse, but considering the fact that this is the Boston premier of The Man From London, nearly three years after its Hungarian premier, I’m not sure when we’ll actually see it. He’s claimed that The Turin Horse, which is rumored to be in consideration for Cannes this year, will be his last film. If this is true, then to simply call it a tragic loss for cinema would not be enough. The comparison has probably been made enough, but Tarr is the Andrei Tarkovsky of his generation. Not so much in an ideological sense, or even an aesthetic one, beyond their shared affinity for slower, more contemplative cinema, but in their greater shared mastery of cinema as an art. If that comparison must go on, then this is Tarr’s Nostalghia or his Sacrifice. For the first time in his career, Tarr’s film is not explicitly set in his native Hungary and does not concern itself with the problems of that nation, but rather society as a whole. Of course, rather than Tarkovsky’s forced exile, this was a choice afforded to him by the greater success of his last two films. This is the natural progression of his work, and while the film may not achieve the beautiful perfection of his last two, it is still a great film and a vital work in understanding the art of one of film’s greatest minds.

Bela Tarr is my favorite filmmaker, and The Man From London, coming soon to the MFA, is only his third film in the last twenty years. The last two, 1994’s Satantango and 2000’s The Werckmeister Harmonies are my favorite films of their respective decades, and the later is also simply my favorite film. Unless some kind soul decides to do a much-needed retrospective of his work, this will, in all likelihood be the only review of one of his films I write for this site. He has another film in production at the moment called The Turin Horse, but considering the fact that this is the Boston premier of The Man From London, nearly three years after its Hungarian premier, I’m not sure when we’ll actually see it. He’s claimed that The Turin Horse, which is rumored to be in consideration for Cannes this year, will be his last film. If this is true, then to simply call it a tragic loss for cinema would not be enough. The comparison has probably been made enough, but Tarr is the Andrei Tarkovsky of his generation. Not so much in an ideological sense, or even an aesthetic one, beyond their shared affinity for slower, more contemplative cinema, but in their greater shared mastery of cinema as an art. If that comparison must go on, then this is Tarr’s Nostalghia or his Sacrifice. For the first time in his career, Tarr’s film is not explicitly set in his native Hungary and does not concern itself with the problems of that nation, but rather society as a whole. Of course, rather than Tarkovsky’s forced exile, this was a choice afforded to him by the greater success of his last two films. This is the natural progression of his work, and while the film may not achieve the beautiful perfection of his last two, it is still a great film and a vital work in understanding the art of one of film’s greatest minds.

The film’s first shot will tell you all you need to know about Tarr. It is a point-of-view shot from Maolin, the protagonist, as he sits in his guard tower at the local docks. He sees a ship come in and stop, the passengers get off, except for a couple who are involved in some shady dealings with a brief case, then he looks at the other passengers as they board a train. This shot takes twelve minutes. It’s not his best opening shot, that prize would certainly go to Werckmeister Harmonies, but the slow pace and brilliant composition mark the shot as something that only he could create. There’s some background chatter in the beginning, but there is no dialogue until the film hits the thirty minute mark, only incidental noise and a brilliant ambient score by his regular collaborator, Mihaly Vig. There’s one thing I did notice in the minimal dialogue that I found to be extremely disturbing: when I first saw this film a year ago, it was in Tarr’s native Hungarian. The screener I watched was in French. I really hope that this was just the screener and not the print that MFA will be screening, but shame on whoever did this. I’m sure it was just a misguided attempt to make the film more accessible, but it’s just unacceptable to dub it like that. Anyway, among other things, the film is a homage to classic film noir. Consider a shot about a third of the way through the film: Maolin wakes up, goes to his window and looks at the street below. At first, the only light comes from his bed-side lamp, and the outside is pitch-black, but then the camera pans down to reveal the titular man from London standing next to a street lamp, staring back up at Maolin. Their bodies are basked in light, but everything else is an exaggerated dark. This shot, held on its own, is pure noir. The high contrast lighting and menacing situation clearly place it in the genre, but instead of cutting away like a traditional noir shot, this lingers, and the ominous music, combined with a very slow zoom onto the man below, creates a sense of dread beyond anything classic Hollywood could have ever produced.

Unlike Tarr’s last two films, The Man From London was not based on a book by his friend and co-writer Laszlo Krasznahorkai, but rather one by Georges Simenon, a prolific Belgian writer whose work has previously been adapted by filmmakers ranging from Renoir and Clouzot to Melville and Chabrol (twice). That wasn’t the only change for his first international coproduction, as the hassles expected with that level of work followed him to this project, starting with the death of the film’s producer/financer just days before production began, which led to various delays totaling nearly two years. Of course, there are certain advantages to an international production. Maolin’s wife is played by Tilda Swinton, which is particularly interesting, as I’m fairly sure she cannot speak Hungarian (apparently it’s an extraordinarily difficult language), so she took a (presumably) low-paying role that wouldn’t even allow her voice to be heard simply to work with Tarr, which is why she is awesome. Unfortunately, the voice acting in the French dub is subpar all around. It’s nowhere near as important in this film as it would be from most other directors, but it is an annoyance.

Critics have universally praised the film’s formal aesthetic, but they have been sharply divided on the work as a whole. A few have correctly pointed out its worthwhile place in Tarr’s body of work. Most mainstream reviewers have complained about its lack of narrative depth, unlikeable characters and alienating effects on the audience. The same group of critics once had the exact same complaints about L’avventura. That film is still beloved. Those critics aren’t. They complain that it’s less lyrical and more formal than his last two, ignoring the fact that it should be seen as more of a companion piece to his 1988 film Damnation than as an ideological sequel to Satantango and Werckmeister. Of course, they are perfectly right to praise the film’s look. It is absolutely beautiful. The camera moves much less than in his other works, and is instead focused on creating pristine symmetry and capturing the details of the lighting and mise-en-scene. Instead of flowing across the action, the camera stays in place and constantly zooms in and out. The high contrast and intense shadows help with the noir aesthetic and create a different (not better or worse, simply different) type of beauty than Tarr has achieved before.

You’ll notice that I’ve avoided plot description. There is more of a concrete plot than in Tarr’s last two films, but it’s still unimportant. This is a series of images, each as beautiful as the last. Whatever it is that ties them together exists for the sake of the image and not the other way around. The film is an incisive study of capitalist Europe, but the images alone do enough to get that across. Dialogue and character are only perfunctory details. People who complain about the film’s lack of either don’t understand the power of the image. In the film, people talk, drink, dance (all of his films feature a dance sequence bordering on absurdity), steal and kill. None of these things matter. Nothing any of the characters do in their lives has any actual meaning. The audience is alienated from these actions because the characters have been alienated by selfish greed and the general meaninglessness of their existence. Tarr isn’t a communist. When Hungary was a communist country, he was just as critical of that system. He simply sees that the system is broken. It always has been and always will be.

When your last film is the peak of the medium as an art form (of course, this is just my opinion, which should never be taken that seriously), there’s bound to be something of a letdown. I knew that coming in, and I just accepted it. This is a great film in its own right. It may be one of the best of the last decade. I’m assuming that most people have never seen a film by Tarr (and for those who have, congratulations, leave comments, what’s your favorite?), so you won’t even have that possible disappointment to worry about. Because of that, I’m begging you to see this film when it is in town. It won’t be here long, but if you love cinema, then you must take this rare opportunity to experience the work of one its true masters on the big screen, as it was meant to be seen.

-Adam Burnstine

The Man From London is unrated and in Hungarian (or French, I guess, depending on the print) and English with English subtitles

The film will begin a week-long run at the Boston Museum Of Fine Arts On January 20th

Directed By Bela Tarr; written by Bela Tarr and Laszlo Krasznahorkai; based on the novel L’Homme de Londres by Georges Simenon; director of photography, Fred Kelemen, edited and co-directed by Agnes Hranitzky; original music by Mihaly Vig; production designers, Jean-Pascal Chalard, Agnes Hranitzky and Laszlo Rajik; produced by Humbert Balsan, Christoph Hahnheiser, Paul Saadoun, Bela Tarr, Gabor Teni and Joachim von Vietinghoff; released by IFC Films. Running time: 2 hours 19 minutes.

With: Miroslav Krobot (Maolin), Tilda Swinton (Camelia), Istvan Lenart (Morrison), Agi Szirtes (Mrs. Brown), Erika Bok (Henriette) and Janos Derzsi (Brown).