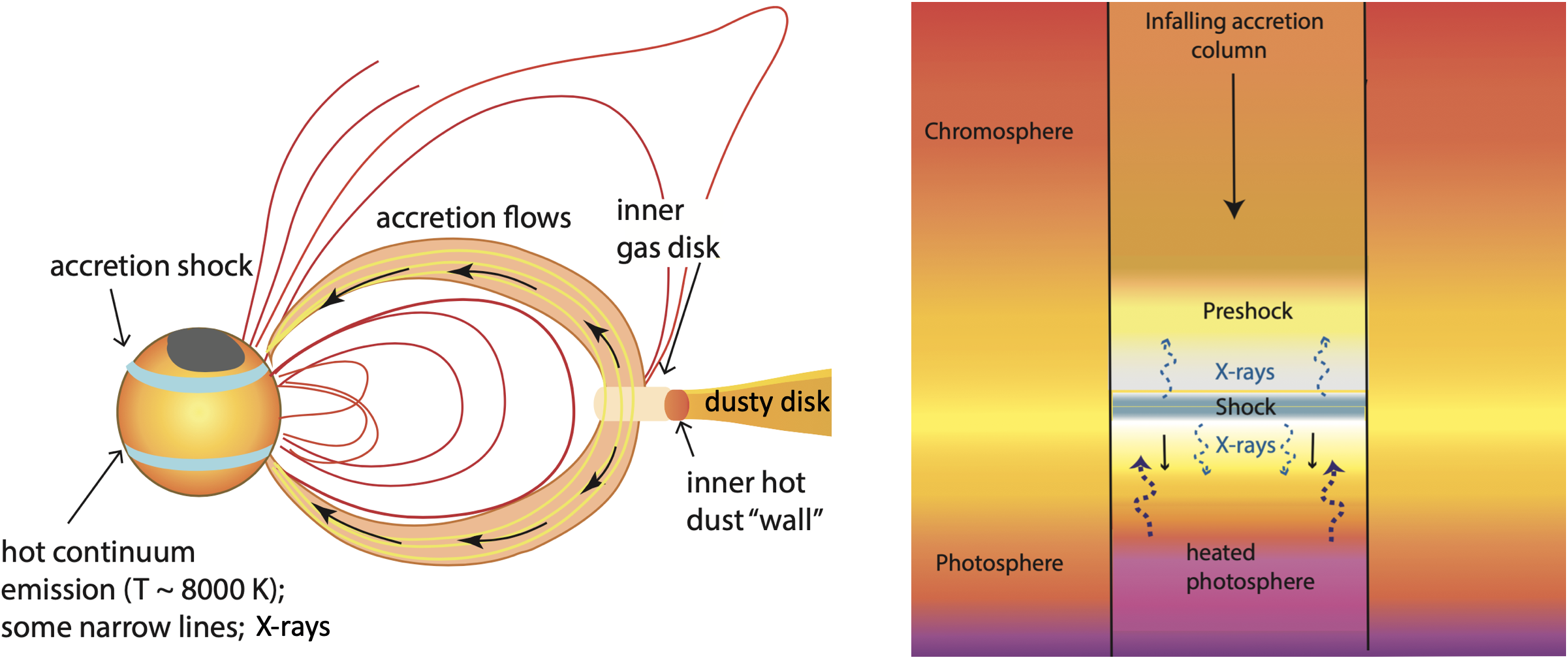

The search to understand how planets form is one of the most fundamental in the field of astronomy, and it connects our own history on Earth to the distant planet-forming regions in the Milky Way and beyond. Emission caused by mass accretion onto stars is a key mechanism for heating protoplanetary disks, which determines the chemistry of the protoplanetary material and drives disk evolution. Thus, it is an integral component of the planet formation process and may dictate the type of planets that form around a given star.

As a member of the ODYSSEUS collaboration, I have modeled ultraviolet through near-infrared Hubble Space Telescope observations from the ULLYSES program, as well as high-resolution optical spectra, in the largest and most self-consistent study of T Tauri star accretion to date. I have then connected accretion to stellar and disk rotation with TESS to characterize angular momentum transfer in the inner disk. My work is fundamentally multi-wavelength, making use of HST, JWST, TESS, VLT, IRTF/SpeX, SMARTS/Chiron, LCOGT/NRES, SOAR/Goodman, as well as archival observations from Spitzer and SOFIA. I explain these observations using models of the magnetospheric accretion flow, accretion shock, and inner gas and dust disks. My full publication list can be found on NASA ADS.

In Pittman et al. (2022), I presented the first model of the star, accretion shock, and inner dust disk that simultaneously fit the UV–IR continuum. This demonstrated that accretion emission can remain significant towards longer wavelengths than previously assumed.

In Pittman et al. (2025a), I established that inner gas disks extend much closer to the host star than previously thought (providing a much simpler formation pathway for ultra-short-period planets, see Pittman et al. 2025b). I showed that up to 50% of the continuum accretion luminosity can come from UV wavelengths, and the absolute UV accretion luminosity spans almost four orders of magnitude (see figure to the right). This has significant implications for interpreting chemical signatures in JWST observations, so, in ongoing work, I am quantifying the astrochemical effect of this large UV range.

In Pittman et al. (2025b), I demonstrated that most CTTS are not near equilibrium spin states, calling attention to a major assumption typically made in theoretical analyses (see figure below). I performed the first statistically-significant observational test of predictions for accretion-powered stellar winds, magneto-hydrodynamic outflows, and magnetospheric variability. I showed that angular momentum loss processes are efficient, causing CTTS rotation rates to remain below equilibrium even while accreting from their disks. I also demonstrated that dipper systems occur irrespective of the relationship between the magnetospheric truncation radius and the Keplerian corotation radius, contrary to theoretical expectations.

In Pittman et al. (2025c), I discovered that the orientations of sub-au scale stellar magnetospheres in Lupus are correlated over parsec scales, rather than being uniformly distributed. The spatial correlations likely reflect molecular cloud collapse driven by massive stellar feedback. This reveals a star-cloud connection that persists over Myr timescales, with important implications for exoplanet observational bias corrections if such anisotropy propagates into orbital inclinations.

I am actively involved with analyses of JWST observations of Class 0 (D. Watson et al. 2025) and Class II (M. Volz et al. 2025, Thanathibodee et al., in review) sources, as well as SOFIA observations of warm disk winds (Pittman, Gorti & Espaillat, in prep). I have ongoing observational programs to examine the temporal variability of magnetospheric accretion processes in individual CTTSs (Pittman et al., in prep).

I am currently applying to postdoctoral research positions to begin around 1 September 2026. Interested in collaborating? I’d love to hear from you!

Header image credit: ALMA (ESO/NAOJ/NRAO), S. Andrews et al.; NRAO/AUI/NSF, S. Dagnello