Inflation. It’s a word that sends shivers down the spine of almost anyone who has never studied it. To some, the word is a signal that their money is about to be worth a lot less than it is now. To others, it’s an indicator that the economy is headed for disaster.

So what exactly is inflation? Essentially, it just means that price levels of common goods and services are rising.

In fairness, these concerns are not without good reason. High levels of inflation can be devastating to an economy, driving up prices at a level that outpaces economic growth, leaving people with hard-earned money that’s worth a fraction of what it was worth when they received the money, or agreed to work at that specific rate. It also can affect the companies paying those employees. Despite being able to sell their product for higher prices, all the costs associated with those products rise as well, as do the salary demands of current and future employees. Many of the world’s most impoverished countries have extremely high inflation, which is ultimately caused by the printing of money at too fast a rate. Even when this is done with good intentions, it almost always results in the steep devaluation of a currency, as happened in Zimbabwe, where the currency became virtually worthless before being discontinued.

There are however, some potential benefits of inflation. The famed (and now somewhat disputed) Phillips Curve, created by A.W. Phillips, indicates that there’s an inverse relationship between inflation and unemployment, so that when inflation rises, unemployment falls. Another key (and more solidly proven) benefit is that inflation eventually corrects fixed prices that may have been set too high.

Most importantly, however, since much of the theory around inflation revolves around the assumption that inflation will cause people to spend more money (since their money is increasingly becoming less valuable with time), many believe that moderate levels of inflation boost spending, consumption and economic growth. In the absence of inflation – deflation – consumers theoretically would be reluctant to spend their money, which is becoming increasingly more valuable, in turn slowing down the economy.

Other potential benefits of inflation are that it makes it easier for debtors to repay loans, since the money they’re giving back is worth less than the money they borrowed, which in turn encourages borrowing and lending. There is also the belief that the more money in existence, the more spending there will be, which is good for everyone. Of course any potential benefit of inflation is only related to moderate levels of inflation. There are virtually no benefits of very high inflation, aside from the psychological effect of seeing higher numbers in one’s bank account.

Because of the economically terrifying risks of deflation, and the theory that (to an extent) the more money most developed countries have in circulation, the more spending will increase, most developed countries actually have a target inflation level above 0. Usually this is between 2-5%. For the United States, for example, the Federal Reserve aims for a 2% inflation rate, which it sees as the perfect safe zone to avoid deflation without worrying about runaway inflation. The U.S. hasn’t always hit that number of late (five of the last seven years the inflation rate has been below 2), but has managed to keep inflation at a relatively stable rate, never exceeding 3.4% or falling below 0 (deflation) over the last 15 years with the predictable exception of 2008 (3.8% inflation when the recession hit) and 2009 (-0.4% at the beginning of the recovery).

So given all we know about inflation, how is Guatemala doing?

Well, for a developing country, pretty darn good. For poor countries, minimizing runaway inflation can be a tremendously difficult if not impossible objective, but Guatemala has been the exception.

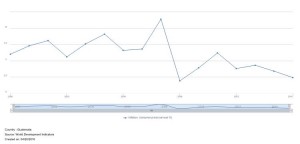

As you can see on the chart below feom the World Bank’s World Development Indicators, Guatemala struggled to reel in inflation during the early part of the 21st century, teetering between 5-9% before a high of 11.4% brought on by the recession. Since then, however, inflation has exceeded 4.3% just once, and currently sits at a healthy 2.4%.

This range has generally hit Guatemala’s target of 3-5% annual inflation, according to the IMF, which also states that “prudent macroeconomic policies have helped maintain relatively low inflation and a strong foreign reserve position.”

To the surprise of many Phillips Curve defenders, there is little correlation between Guatemala’s inflation level and unemployment, however there does seem to be positive correlation between moderate inflation increases/decreases and GDP growth/retraction.

What does this all mean for Finagle? Frankly, a stable currency is something of an unexpected luxury in a developing country, and a pleasant surprise. While this provides little advantage compared to operation in the U.S., it does provide Guatemala with a leg up on many of it’s Central and South American neighbors.

Running out of steam? Learn about energy in Guatemala here.

which one is worse, inflation or resession??