By Rajesh Gururaghavendran

One of the most important hallmarks of success in academia is publication. It is the holy grail of all academic and research endeavors. Common queries from students interested in research endeavors usually are about publications. The present blog is an attempt to piece together various pointers for scientific writing that I have accrued over a period of time. There is no specific recipe for successful publications. Kindly bear in mind that these are just pointers and not definitive mantras for successful publications.

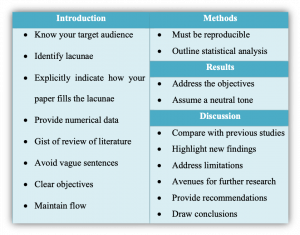

A majority of the publications will follow the IMRAD format, which indicates Introduction, Methods, Results and Discussion. I will trace the critical components in this blogpost using the IMRAD structure.

Introduction:

Know your target audience:

One must consider the target audience that the proposed article is addressed to. The simplest individual in the intended target audience should be able to read and comprehend the introduction. It is preferable to avoid all technical jargon and keep it rather simple.

Identify lacunae:

The introduction section should clearly identify the gaps in the present knowledge in the proposed area of research. There is no point in “re-inventing the wheel” and research endeavors should essentially attempt to generate new knowledge.

Explicitly indicate how your paper fills the lacunae:

Specify how exactly your research work contributes towards filling the knowledge void. One can indicate that there are very few papers or no papers which have explored this aspect of the research topic.

Provide numerical data:

A common man will be able to relate to numbers more easily than vague indicators. This is one of the most critical pointers that I realized during my writing assginments/projects during my first semester. Providing numerical data in terms of the number of individuals affected by the problem will add a lot of clarity to the manuscript. This information should be from authentic sources such as Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), World Health Organization (WHO), etc. Data provided should also be as recent as possible, which will lend a lot of relevance and credibility to the manuscript.

Gist of review of literature:

Review of literature is an important component of any research protocol. One must keep in mind that scientific papers do not have a separate section for literature review. Invariably, we will have to integrate the most important papers from review of literature section into the introduction section.

Avoid vague sentences:

Writing vague sentences “This particular problem has a substantial impact on the health of young adults in the US” do not convey any clear information. This can be modified as “A total of XXX deaths have been reported due to this problem among young adults in the US” or “1 in 5 young adults are affected by this problem in the US”.

Clear objectives:

Explicitly indicating the objectives of the present research work is very critical. It provides clarity of thought and a clear purpose in conducting this research. The acronym SMART objectives provides a useful guideline for framing objectives. The stated objectives should be Specific, Measurable, Achievable, Realistic and Time Bound. FINER criteria also provides a helpful framework and stands for Feasible, Interesting, Novel, Ethical and Relevant. The acronym PICOT, which stands for Population, Intervention, Comparison, Outcomes and Time, is a useful outline for reporting interventions.

Having clear and explicit objectives will set the tone for the rest of the manuscript.

Maintain flow:

Last but not the least, the introduction section should flow seamlessly from one aspect to the other. There should not be any portions that do not gel with the overall scheme of the introduction. Having the manuscript proofread by your peers, seniors, or juniors will go a long way in addressing this issue.

Methods:

Have to be reproducible:

Methods section should be clearly written so that any other researcher should be able to implement the same study in a similar fashion.

Outline statistical analysis:

Clearly indicate what statistical tests were employed and the statistical package that was used for statistical analysis.

Results:

Address the objectives:

One must bear in mind that the results should clearly address the objectives laid out in the introduction section. This will provide focus to the researcher to ensure that the objectives are met. Some of the funding agencies will ask for results to be presented for each of the objectives indicated by the researcher. This implies that results section should address all objectives outlined by the investigator.

Assume a neutral tone:

Results section should objectively highlight the results obtained by the investigator. Judgement calls, researcher’s opinions should be avoided in this section.

Discussion:

Compare with previous studies:

Comparison with previous studies and enunciating the probable reasons for similarities/differences are central to discussion. If there are many aspects of the findings, which is often the case, only the main findings of the study can be used for comparison.

Highlight new findings:

New findings in the present study must be highlighted. Research initiatives will usually involve a component or aspect that is new. Findings relevant to these new areas pertaining to the research topic must be highlighted.

Address limitations:

Clear and frank descriptions of limitations must be stated. No study is perfect and there will be some limitations due to practical reasons. Authors should not shy away from addressing these limitations explicitly in the manuscript.

Avenues for further research:

Research, by its very nature, is heuristic and will lead to further questions. Avenues for further research that stem from the findings of the present study must be outlined.

Provide recommendations:

This will involve public health measures that can be implemented to address the health issue being addressed in the paper. This may also involve policy changes, curriculum implications, lobby efforts that can lead to positive changes leading health improvements in populations.

Draw conclusions:

Conclusions that are in line with the objectives outlined must be stated. Some journals ask for conclusions to be stated under a separate sub-heading. The last few paragraphs of the manuscript usually comprise of conclusions.

You can email me at: rajeshg@bu.edu

Writing can be utilized as a means of communicating information about a serious health issue at hand. Writing assignments will have a different context compared to a press release about the need for vaccination. Based on the context, the nuances of writing will be different. Understanding the context will help the author to get the right content for their message.

Writing can be utilized as a means of communicating information about a serious health issue at hand. Writing assignments will have a different context compared to a press release about the need for vaccination. Based on the context, the nuances of writing will be different. Understanding the context will help the author to get the right content for their message.