Are you working on a public health writing project that requires you to find and synthesize information from multiple articles on a particular public health topic? Reviewing and synthesizing sources is a common task for public health researchers and other professionals who need to develop a snapshot of what is known about a particular health challenge or intervention.

While the task may sound simple, the amount of information you are finding can quickly become overwhelming. Developing a literature review table is a particularly useful way to keep track of your sources and take systematic notes.

The Complex Task of Looking for and Keeping Track of Sources

Many things are going on simultaneously when you start looking for sources via PubMed, Web of Science, Google Scholar, and other search engines. As you are doing that, you refine your search and screen titles and abstracts. Then you choose the articles that are most relevant to your task and download PDFs or save them in your Mendeley or Zotero library.

But what do you do next? Maybe you highlight information that you find most intriguing and relevant. Maybe you print out your sources and use an actual yellow marker. Maybe you take notes. Or maybe all that information gets confusing. You lose your sense of direction and purpose and struggle to figure out what is most relevant to your assignment.

This is where the literature review table comes in. It’s a great way to reassert some control over your material, sort it, and extract the information most relevant to your task. Take a look at the template below. You can adjust the column headers in whatever way is must useful to your task.

Remember, the idea is that you are using the table to help you decide what information is most important to your task. The goal is to be selective about the details you include. (See below for links to examples of lit review tables in published articles.)

Table 1: Literature Review Table Template

| Author / Year / Citation | Study Objective | Key Study Methods | Key Findings | Study Design Limitations |

|

|

· | Information to include:

|

Choose 1-3 findings.

Work in some specific numbers that will be useful when writing. |

|

The literature review table is a tool that will help you:

Extract information systematically from your sources: First, the table is a tool to help you extract information in a systematic way. Each column reminds you to look for and record key information such as the size and characteristics of the study population, the research question, the intervention being tested, and the study design. These notes provide context that will help you understand and think critically about the findings of the study and their relevance to the population and public health challenge you are researching.

Evaluate studies side-by-side: Second, the table allows you to see the details of your sources side-by-side, which will help you to see common themes, gaps, and potential new areas of inquiry. When I don’t do a table, I find that notes exist as a vague jumble of information in disparate places. I sometimes print the studies, underline, and take notes in the margins. Other times, I put my notes onto a legal pad or right into my draft. More and more, I have no hard copies. I simply highlight pdfs and then have to remember where they are saved on my laptop. (Are they in Dropbox, in my Mendeley library, or squirreled away somewhere else?) What I can’t see, I quickly forget.

Feel more confident as you begin writing: When I use a table while taking notes, I don’t have to worry about what I might be forgetting. All I need is right there. So the next step, summarizing and analyzing the information, comes much more easily. I write a short introduction providing a brief overview of my research and decision-making process (why I chose these 5 studies), then I look for key themes and highlight some of the most useful findings. Once, I’ve gotten this far, thinking about the implications of the research, along with methodological strengths and limitations, also comes much more easily.

Be nice to your reader: Third, the table is also a nice thing to do for your readers. When you include your lit review table your document, you are providing them with detailed snapshots of individual studies and allowing them to decide if they want to track down the article to read more.

Lift the “heavy cargo” from your text: Another bonus is that putting details like study methods, statistics, p-values, and study limitations in the table saves your text from having to carry all that weight. You can refer readers to the table and use your text to emphasize the details you think are most important. I once, for example, was able to cut 10 pages of unnecessary summary out of a literature review draft when I realized that most of the studies I was able to find danced around my research question, but never really answered it. Ten pages became 2 sentences and a note referring readers to the table. This draft was much easier to read than my first. (Roy Peter Clark talked about putting the heavy cargo from studies into a figure or chart in his wonderful book Tell It Like It Is: A Guide to Clear and Honest Writing (2023). It’s a must-read for all public health writers!

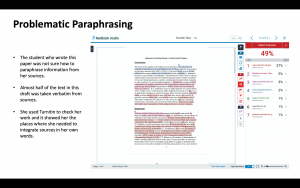

Being Strategic About the Information You Put in the Table & A Note of Caution: Don’t Turn the Table Into an Excuse to Delay Writing

You don’t need to record every detail in each article. It’s easy to get so detail-obsessed that the table becomes a form of procrastination. Instead, focus on the findings that help you understand or answer your research question.

Think of it this way. You want enough detail that you won’t need to go back to the original articles when you write your summary. Use the table to write your summary, then you can skim back through the articles to see if there are additional details you need to add in.

You can also think about it from the perspective of your reader. You are doing them a favor by including enough detail so they won’t need to dig out the original article to get a basic grasp of your topic or follow your summary and analysis. You are providing just enough information to fulfill their basic curiosity and help them decide if it’s worth their while to find and download the article.

Examples of Literature Review Tables in Published Articles

Beard J, Feeley F, Rosen S. Economic and quality-of-life outcomes of antiretroviral therapy for HIV/AIDS in developing countries: a systematic literature review. AIDS Care. 2009 Nov. 2(11): 1343-56. (Tables start on pages 1347 & 1349)

Patmisari E, Huang Y, Orr M, Govindasamy S, Hielscher E, McLaren H. Supported employment interventions with people who have severe mental illness: Systematic mixed-methods umbrella review. PLoS ONE. 2024 June. E 19(6): e0304527. (Table starts on page 14/37)

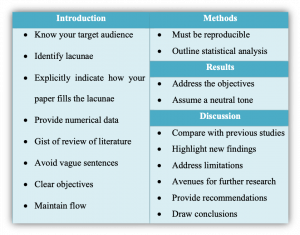

Writing can be utilized as a means of communicating information about a serious health issue at hand. Writing assignments will have a different context compared to a press release about the need for vaccination. Based on the context, the nuances of writing will be different. Understanding the context will help the author to get the right content for their message.

Writing can be utilized as a means of communicating information about a serious health issue at hand. Writing assignments will have a different context compared to a press release about the need for vaccination. Based on the context, the nuances of writing will be different. Understanding the context will help the author to get the right content for their message.