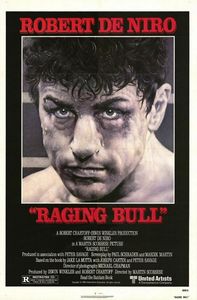

Martin Scorsese’s Raging Bull is often called a “boxing movie,” and grouped alongside the likes of Rocky in discussions of such things. The American Film Institute, for its part, proclaimed it the No. 1 sports movie of all time. The label is erroneous. Raging Bull concerns itself with many things, but sports is not chief among them.

Martin Scorsese’s Raging Bull is often called a “boxing movie,” and grouped alongside the likes of Rocky in discussions of such things. The American Film Institute, for its part, proclaimed it the No. 1 sports movie of all time. The label is erroneous. Raging Bull concerns itself with many things, but sports is not chief among them.

Raging Bull is a poem about jealousy and paranoia above all else. Specifically, it’s about the guilt and hunger of its protagonist, Jake LaMotta (Robert De Niro), who uses the boxing ring to unleash his rage against, not his opponents, but the people in his daily life, especially his wife Vickie (Cathy Moriarty), of whom he suspects nothing but unsavory deeds.

Aspiring writers are told “show, don’t tell,” and Raging Bull, written by Paul Schrader and Mardik Martin from LaMotta’s autobiography, contains one scene after another that suggest Jake’s jealousy without him ever having to confess it outright. The cinematic techniques are well-known—particularly Scorsese’s use of slower camera speeds that observe Vickie with careful attention—but the film’s most effective means of portraying Jake’s monstrous character is through dialogue.

To be sure, Jake is not the kind of man to express his feelings directly or articulately; he functions entirely through action and instinct, and this gives the boxing scenes their brutalizing power. However, the heart of the matter plays out well before Jake strings up his boxing gloves, and it nearly always seems to stem from his suspicions about his wife.

Consider the great sequence regarding his fight against Tony Janiro, a young up-and-comer with a “pretty boy” image. During a fast-paced argument in the kitchen about Jake’s prospects, Vickie casually and innocuously calls Janiro “good-looking.” Jake stops the discussion dead in its tracks, demanding Vickie explain what she means. Impatiently, she does so, but Jake is unsatisfied: How dare she feel anything for another man, let alone one of his opponents. Vickie calls him crazy. Later, he asks his brother and manager Joey (Joe Pesci) what Vickie might be up to; he calls him crazy, too, but Jake is undeterred in his suspicions. His way of latching onto a single word or phrase, twisting and exhausting its meaning until he has driven himself absolutely up the wall, is hypnotic and frightening for a man whose profession is to beat the stuffing out of his fellow travelers.

The payoff to this sequence—the LaMotta v. Janiro showdown—is doubly effective because it has been set up so clearly. Jake does not merely defeat Janiro; he pulverizes him, landing punch after punch with a ferocity unparalleled in his career up until then. This fight, more than any scene in the film, illustrates boxing’s contradictory function as both an outlet for violent, abusive men, but also as a means (often to futile ends, as here) of preventing that violence from spilling into the domestic sphere. As the fight ends, Jake shoots a triumphant look directly at Vickie, who sits uneasily amongst the crowd. The point is made.

The year 2010 marks three decades since Raging Bull premiered, and I cannot say with confidence that a finer film has been made in the intervening time. Scorsese’s picture considers the most base and horrid facets of human behavior—envy, suspicion, male subjugation of women—and, for all its technical mastery, ultimately succeeds only because it is so dreadfully, painfully true.

-Dan Seliber