If you had come up to me a year-and-a-half ago, told me that David Lynch was producing a Werner Herzog film and asked me what it was going to be about, “guy kills his mom with a samurai sword to act out Aeschylus’ Oresteia and takes two flamingos hostage” probably wouldn’t have been too far down the list. If you had told me there would be a dwarf in the film, it probably would have been my first choice. I think the surprise would have come if you’d told me that My Son, My Son, What Have Ye Done? would be one of the best things either one of them has ever been involved with. I’ve never been stingy with my praise of Herzog and his work. In my review of Bad Lieutenant: Port Of Call New Orleans (his other surreal , awkwardly titled cop movie from last year, which I’ve been assured was just a coincidence), I called him “almost unquestionably the most influential living European filmmaker after some of the surviving members of the Nouvelle Vague,” a group that sadly shrunk by one recently with the death of Eric Rohmer. I stand by that, and I would like to add that Herzog is also one of the few still pretty routinely putting out great films, as My Son, My Son is his best since Stroszek, and, of the fifteen or twenty of his films that I’ve seen, I honestly believe it would rank third. Herbert Golder, a professor of classics at BU and the film’s co-writer, presented the film and mentioned, among other things, that Herzog considered this an intensely personal film and preferred it to the more studio-driven Bad Lieutenant. Of course, Herzog is right to do so; it is the better film.

If you had come up to me a year-and-a-half ago, told me that David Lynch was producing a Werner Herzog film and asked me what it was going to be about, “guy kills his mom with a samurai sword to act out Aeschylus’ Oresteia and takes two flamingos hostage” probably wouldn’t have been too far down the list. If you had told me there would be a dwarf in the film, it probably would have been my first choice. I think the surprise would have come if you’d told me that My Son, My Son, What Have Ye Done? would be one of the best things either one of them has ever been involved with. I’ve never been stingy with my praise of Herzog and his work. In my review of Bad Lieutenant: Port Of Call New Orleans (his other surreal , awkwardly titled cop movie from last year, which I’ve been assured was just a coincidence), I called him “almost unquestionably the most influential living European filmmaker after some of the surviving members of the Nouvelle Vague,” a group that sadly shrunk by one recently with the death of Eric Rohmer. I stand by that, and I would like to add that Herzog is also one of the few still pretty routinely putting out great films, as My Son, My Son is his best since Stroszek, and, of the fifteen or twenty of his films that I’ve seen, I honestly believe it would rank third. Herbert Golder, a professor of classics at BU and the film’s co-writer, presented the film and mentioned, among other things, that Herzog considered this an intensely personal film and preferred it to the more studio-driven Bad Lieutenant. Of course, Herzog is right to do so; it is the better film.

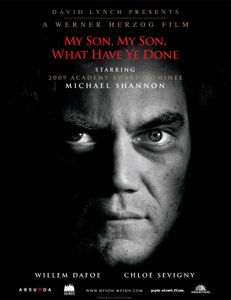

The film is loosely based on a true story of a young actor in San Diego who killed his mother with a samurai sword while rehearsing for the role of Orestes, a major character in Greek myth who killed his mother with an antique sword. In the film, he’s named Brad McCullum, and played to perfection by Michael Shannon, who could have taken any easy Hollywood role he wanted after his Oscar nomination a year ago, and has instead taken parts in two Werner Herzog films. His mother is Lynch-regular Grace Zabriskie. He thinks she controls him and forces him to stay at home and do what she wants, but he somehow managed to go on a rafting trip in Peru with his friends, so I don’t know how much of her control was real and how much was imagined. That Peru trip was the apparent catalyst for his entire mental breakdown. His friends wanted to kayak down some very dangerous (and, for the Herzog aficionado, very familiar looking) rapids, but Brad had an inner voice tell him to stay back, and the others all drowned. When he got back to America, he started acting strange and searching for God in random places. I won’t tell you where he finds his answer because it ruins one of the film’s funniest scenes. His fiancée Ingrid, played by Chloe Sevigny, and his friend Lee, played by Udo Kier, try to help him and decide to co-write and produce Aeschyluss’ Oresteia with Brad as Orestes. At one point, Brad and Lee go to Brad’s uncle’s Ostrich farm to pick up a samurai sword that his uncle Ted (Brad Douriff) has lying around and they want to use as a prop. The ostriches eat Lee’s glasses and provoke some bizarre insights from Brad. Uncle Ted doesn’t understand the importance of the theater, but he seems to support Brad in ways that his mother never does. All of this comes from flashbacks told to the two detectives who are investigating Brad’s mother’s murder as Brad sits in his house with two hostages. The detectives are played by Willem Dafoe and Michael Pena, who both do a very good job with some very strange dialogue.

This is an extraordinarily unsettling film. It becomes clear early on that everything, even the other character’s flashbacks, is shown from Brad’s perspective. Everyone in a scene will occasionally stop and stare at the camera, a glass tube becomes a tunnel through time, flamingos and ostriches become symbols of something greater and people talk about dwarfs riding horses and being chased by giant chickens. Early on in the hostage crisis, he yells out “God is in the house with me, but I don’t need him anymore,” and then he rolls his God out of the garage. His hostages are flamingos, although the cops don’t know it. The dialogue, especially the stuff involving the cops seems like it was written by an insane narcissist who watches too much TV, and many of his best lines were taken from the real killer. This awkward, occasionally nonsensical dialogue gives the film some much-needed humor (as he’s arrested, Brad proclaims “I hate it that the sun always comes up in the east”). There are also some very serious sequences involving Brad’s mental illness. He walks around a market in Western China (why he’s there is never explained), asking why everyone is looking at him, and the entire scene is done from his point of view. People stare at the camera, and we begin to feel Brad’s paranoia, which is only compounded by the music. The score is ambient and atonal, and it never lets up. Brad is, presumably due to his mental illness, an incredibly narcissistic character, so obsessed with his own observations and ideas that he completely shuts out everyone else in the world, so his actions ultimately make a bizarre sort of sense. He took a myth that’s been around for 2000 years and acted it out so that he would be remembered for just as long.

Lynch was not involved with writing or directing the film, but his touch is there, most notably in the use of handheld digital cameras, although Herzog never takes it to the same extreme as Lynch did in Inland Empire, and instead uses the technology to create one of his most aesthetically pleasing films to date. Even though he’d never admit it, I really think this may be Herzog’s most personal feature. The scenes in Peru were meant to be shot in northern Pakistan, but that wasn’t going to happen, so Herzog returned to the river of Aguirre and Ftizcarraldo. Lee is played by the unquestionably German Udo Kier, and the reasonably sane German director being forced to deal with his completely insane, incredibly talented actor brings up memories of Klaus Kinski and My Best Fiend. There are ideas and themes here that have played a major part in so many of his greatest works, including his fascinations with mental illness and the alienated individual in America. When it was over, I realized something. It may eventually be remembered as one of his better films, but that will take a while. If it had been made in the seventies with Kinski or Bruno S as Brad, Bruno Ganz in Dafoe’s role and Eva Mattes as Ingrid, it may have been considered his masterpiece, and I think it should still be in that discussion. Hopefully it will get a national release soon, so that discussion can begin.

-Adam Burnstine

My Son, My Son, What Have Ye Done is unrated.

It will screen at the Boston Museum Of Fine Arts on Saturday, February 6th at 7:00 PM

Directed by Werner Herzog; written by Werner Herzog and Herbert Golder; director of photography, Peter Zeitlinger; edited by Joe Bini and Omar Daher; original music by Ernst Reijseger; art director, Danny Caldwell; produced by Eric Bassett and David Lynch; distributed by IFC films. Running time: 1 hour 31 minutes.

With: Michael Shannon (Brad McCullum), Chloe Sevigny (Ingrid), Udo Kier (Lee Meyers), Willem Dafoe (Detective Hank Havenhurst), Michael Pena (Detective Vargas), Grace Zabriskie (Mrs. McCullum) and Brad Dourif (Uncle Ted).