Radu Mihaileanu’s The Concert is a film about the enduring repercussions of an act of Soviet anti-Semitism…sort of. At times it’s actually more of a comedy about a group of shabby, loud Russian musicians horrifying the starchy Parisian artistic establishment. It’s also a familial drama in which a young woman finds her roots and a father figure through the power of music. In short, The Concert is a few too many things.

That said, it’s a difficult film to dislike. Its appealing hero Andrei Filipov (Alexei Guskov), one-time conductor of the Bolshoi Orchestra, had been fired under Brezhnev for protecting his Jewish musicians. In the middle of a performance of Tchaikovsky’s violin concerto, a Communist lackey stormed onto the stage and snapped his baton in half. Now, decades later, the Soviet regime has fallen, but Filipov is still scrabbling together a lowly existence as a janitor where he once conducted.

Then, in the first of a series of improbable strokes of luck, Filipov intercepts an invitation for the Bolshoi to perform at the Châtelet Theater in Paris. He decides to perpetrate what must be the most admirably-intentioned scam ever conceived in the art world: to reassemble his long-languishing ex-orchestra members, bring them to Paris posing as the real Bolshoi, and finish the concert that was interrupted thirty years ago.

The early scenes play farcically, though anchored by Filipov’s sincerity, as the conductor and his cellist best friend Sacha (Dmitri Nazarov) gather the dissolved orchestra. Broad, if affectionate, stereotypes predominate: a yarmulke-sporting clarinetist who agrees to the venture when Filipov promises that Parisian Catholics have all secularized and the city features “a synagogue on every street”; a roguish gypsy violinist who turns his audition into a riotous dance. Everything seems to go smoothly, because for this film musical talent is more or less a divine spark that never diminishes even after thirty years of dormancy. None of the musicians fail their impromptu auditions–not even the ones who pawned their instruments long ago.

But once in France, the impoverished Russians terrify the Châtelet’s administrators with their brawls, irrational demands and general penchant for mayhem, before sauntering away–bellowing drunkenly, of course–into the Parisian night. It seems Sacha and Filipov were the only ones truly determined to put on a show. Everyone else was just desperate for a pass out of Russia. Can Filipov awaken the love of music within the hearts of his errant musicians and save the faux-Bolshoi Orchestra?

Silly question. It wouldn’t be much of a comedy otherwise. But Mihaileanu makes a strange decision: in an attempt to deal with the tragic backstory, he steers his movie into melodrama. Filipov has requested Anne-Marie Jacquet (Mélanie Laurent), a French classical music star and prodigy, for the Tchaikovsky solo. His reasons for picking her are soon revealed to be more complex than artistic admiration. Anne-Marie has a mysterious connection with the past, and she seems essential to the conductor’s recreation of the ruined concert of long ago. I won’t say more on why this is so, although the script makes it a little too easy to guess. But the film needs all of Guskov’s appeal to smooth over this odd mood change as Filipov the underdog turns into Filipov the haunted genius.

A smoother script would have helped, but even the best comedy writers would have trouble fitting a terrible story of political persecution into the relatively contained frame that The Concert provides for its backstory. Not that humor isn’t allowed to touch the worst of the twentieth century. But The Concert simply doesn’t have room for the emotions that stories about anti-Semitism and repression evoke. It’d rather supply us a sentimental, nonsensical reward for our brush with the past.

Luckily, the payoff sort of works. How many films trumpet the power of our cultural heritage to liberate and unite us? It won’t spoil The Concert to say that it climaxes with the most insane optimism on film since Disney movies dropped their once-perfunctory closing rainbows and off-screen choirs. Tchaikovsky’s violin concerto causes French snobs to throw roses in slow motion, jaded professional critics to dissolve into ecstatic tears, Communists to believe in God, closeted men to kiss each other in helpless rapture, etc. Mihaileanu’s standard of restraint means not showing an entire audience having a collective, musically-induced orgasm.

The Concert is a peculiar film, and not a great one, but its fantasy is temptingly innocent. Like its hero, it wants us to love Tchaikovsky. I can’t resent it much for that.

-Julia Zelman

Directed by Radu Mihaileanu; written by Mihaileanu, Alan-Michel Blanc and Matthew Robbins,; director of photography, Laurent Dailland; edited by Ludovic Troch; music by Armand Amar; released by the Weinstein Company. Running time: 1 hour 47 minutes.

A few weeks ago, Criterion released an excellent box set--a collection of early Josef von Sternberg films. They are a must own for anyone interested in cinema, especially in this new incarnation. The set contains commentaries, documentaries, essays, and two brand new scores from the Alloy Orchestra. I had the opportunity to catch up with Ken Winokur about their contribution to the films, what they've been working on, and what's next.

A few weeks ago, Criterion released an excellent box set--a collection of early Josef von Sternberg films. They are a must own for anyone interested in cinema, especially in this new incarnation. The set contains commentaries, documentaries, essays, and two brand new scores from the Alloy Orchestra. I had the opportunity to catch up with Ken Winokur about their contribution to the films, what they've been working on, and what's next. In the span of two months Criterion has given us two of the best American war films ever made. And again, as with some of the best films about combat, it balances the destruction on and off the battlefield. Paths of Glory, Stanley Kubrick’s version of the trials of three soldiers accused of desertion during a clearly futile attack on the battlefields during World War I, is a visual chess match, the quagmire of the trenches moved to the no-less stalemated courtroom. Opening with some of the best scenes of war yet committed to film, it quickly descends into the palatial headquarters of a war and the dark basements of a prison cell. The new bluray from the Criterion Collection does more than clean up the images; it sheds new light on the production and the man behind the camera.

In the span of two months Criterion has given us two of the best American war films ever made. And again, as with some of the best films about combat, it balances the destruction on and off the battlefield. Paths of Glory, Stanley Kubrick’s version of the trials of three soldiers accused of desertion during a clearly futile attack on the battlefields during World War I, is a visual chess match, the quagmire of the trenches moved to the no-less stalemated courtroom. Opening with some of the best scenes of war yet committed to film, it quickly descends into the palatial headquarters of a war and the dark basements of a prison cell. The new bluray from the Criterion Collection does more than clean up the images; it sheds new light on the production and the man behind the camera. As the brothers Whitman run toward the train, the slow motion photography kicks in, as do the Kinks, and the crescendo of obvious dialogue, “This baggage isn’t going to make it,” is uttered, you may find yourself exhausted. Indeed, when I first saw the film at a press screening half a decade ago, one of the more obnoxious reviewers in the crowd decided it was quite appropriate to sigh throughout the entire film. Wes Anderson has this effect on people, and his last live action film, The Darjeeling Limited is no different. And there are many reasons for this—the style, the repeated themes, the disconnect from the upper middle class world of his characters, even the perfectly crafted soundtracks. All these aspects of his films are both cool and distancing, deep and superficial, dramatic and flat. This is especially true with The Darjeeling Limited because, as Matt Zoller-Seitz remarks in his visual essay on the bluray, it is a distillation of many of Anderson’s themes, both a representation and watermark. This makes the film either entrancing for someone who has never seen an Anderson film or possibly disappointing as his fifth effort. Repeated viewing helps, and now we have that chance, courtesy of a new bluray from the Criterion Collection.

As the brothers Whitman run toward the train, the slow motion photography kicks in, as do the Kinks, and the crescendo of obvious dialogue, “This baggage isn’t going to make it,” is uttered, you may find yourself exhausted. Indeed, when I first saw the film at a press screening half a decade ago, one of the more obnoxious reviewers in the crowd decided it was quite appropriate to sigh throughout the entire film. Wes Anderson has this effect on people, and his last live action film, The Darjeeling Limited is no different. And there are many reasons for this—the style, the repeated themes, the disconnect from the upper middle class world of his characters, even the perfectly crafted soundtracks. All these aspects of his films are both cool and distancing, deep and superficial, dramatic and flat. This is especially true with The Darjeeling Limited because, as Matt Zoller-Seitz remarks in his visual essay on the bluray, it is a distillation of many of Anderson’s themes, both a representation and watermark. This makes the film either entrancing for someone who has never seen an Anderson film or possibly disappointing as his fifth effort. Repeated viewing helps, and now we have that chance, courtesy of a new bluray from the Criterion Collection. What is this war in the heart of nature? This is the question—left unanswered—at the heart of Terrence Malick’s masterpiece, The Thin Red Line. And we are all the better for it. This nearly three hour poem of cinema lingers, asks us questions about life and death, light and shadow, horror and sacrifice, presenting us with only the assurance that e are all alone in this world, yet forever linked to one another. Much to chew on for certain, and given a heightened sense of meaning in the face of war, yet the artistry of cinematographer John Toll and the direction of Malick never lets us down. It only presents the questions.

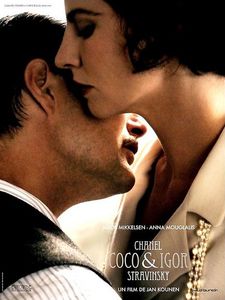

What is this war in the heart of nature? This is the question—left unanswered—at the heart of Terrence Malick’s masterpiece, The Thin Red Line. And we are all the better for it. This nearly three hour poem of cinema lingers, asks us questions about life and death, light and shadow, horror and sacrifice, presenting us with only the assurance that e are all alone in this world, yet forever linked to one another. Much to chew on for certain, and given a heightened sense of meaning in the face of war, yet the artistry of cinematographer John Toll and the direction of Malick never lets us down. It only presents the questions. From the opening sequence of Coco Chanel and Igor Stravinsky, it is clear that the film’s focus is style. An elaborate weave of colors and textures create a kaleidoscope that slowly morphs into the action of the film. Well dressed Parisians float through beautiful spaces in a glamorous Opera Hall waiting for the 1913 presentation of Stravinsky’s music. The tension builds as the camera follows dancers, musicians, choreographers and composers who frantically try to keep the angry audience at bay. Throughout this chaotic scene, Coco Chanel (played by Anna Mouglalis) remains calm and poised, her expression flinching only when she meets the firm and volatile Igor Stravinsky (Mads Mikkelsen).

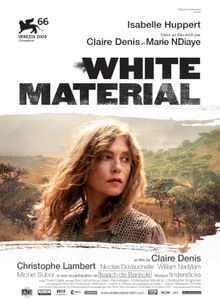

From the opening sequence of Coco Chanel and Igor Stravinsky, it is clear that the film’s focus is style. An elaborate weave of colors and textures create a kaleidoscope that slowly morphs into the action of the film. Well dressed Parisians float through beautiful spaces in a glamorous Opera Hall waiting for the 1913 presentation of Stravinsky’s music. The tension builds as the camera follows dancers, musicians, choreographers and composers who frantically try to keep the angry audience at bay. Throughout this chaotic scene, Coco Chanel (played by Anna Mouglalis) remains calm and poised, her expression flinching only when she meets the firm and volatile Igor Stravinsky (Mads Mikkelsen). One of the few things even resembling a consensus that you will find among film fans is that Claire Denis is the best working female director. Whether she is the greatest female filmmaker of all time or the finest working director period are both up for debate (for the record, I’d say she’s pretty high up there in both categories). This consensus comes from a remarkable mixture of genre-bending narrative experiments, her ability to create profound beauty out of the smallest detail and intensely personal stories told in very personal ways. One of her recurring personal stories is that of the colonial experience in Africa. She was born in France, but spent her entire childhood moving around French colonial Africa with her family. Her first film, 1988’s Chocolate, was an autobiographical study of her own childhood experiences during the end of colonialism. She’s returned to the continent every few years during her career, with 1999’s masterful Beau Travail using Melville’s novella Billy Budd as a basis for a study of masculinity and the role of the post-colonial force. White Material is different. In those films, the relationship between the natives and the colonial/post-colonial forces was strained but reasonably peaceful. Now, nearly fifty years since the end of colonialism, it is time for the entitled to leave a place that they do not understand. Most of the white characters in the film claim to be African, and some go so far as to insult other French citizens, but they are not a part of the land. In her other films, the characters are a part of their environment—in Friday Night the young couple is as much a piece of the film’s central traffic jam as any of the cars and in Beau Travail the soldiers are as much a part of the desert as any natives—but in White Material the characters do not belong, despite their beliefs to the contrary, and this conflict is what carries the film.

One of the few things even resembling a consensus that you will find among film fans is that Claire Denis is the best working female director. Whether she is the greatest female filmmaker of all time or the finest working director period are both up for debate (for the record, I’d say she’s pretty high up there in both categories). This consensus comes from a remarkable mixture of genre-bending narrative experiments, her ability to create profound beauty out of the smallest detail and intensely personal stories told in very personal ways. One of her recurring personal stories is that of the colonial experience in Africa. She was born in France, but spent her entire childhood moving around French colonial Africa with her family. Her first film, 1988’s Chocolate, was an autobiographical study of her own childhood experiences during the end of colonialism. She’s returned to the continent every few years during her career, with 1999’s masterful Beau Travail using Melville’s novella Billy Budd as a basis for a study of masculinity and the role of the post-colonial force. White Material is different. In those films, the relationship between the natives and the colonial/post-colonial forces was strained but reasonably peaceful. Now, nearly fifty years since the end of colonialism, it is time for the entitled to leave a place that they do not understand. Most of the white characters in the film claim to be African, and some go so far as to insult other French citizens, but they are not a part of the land. In her other films, the characters are a part of their environment—in Friday Night the young couple is as much a piece of the film’s central traffic jam as any of the cars and in Beau Travail the soldiers are as much a part of the desert as any natives—but in White Material the characters do not belong, despite their beliefs to the contrary, and this conflict is what carries the film.