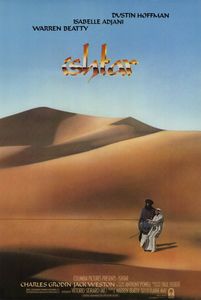

The first time I heard of Ishtar was when I was about 13 years old spending a nice summer’s day inside watching television. Elaine May’s comedy starring Dustin Hoffman and Warren Beatty was on the wrong end of various jokes during an episode of VH1’s ever present I Love The 80s. It was labeled stupid, idiotic and everything else by an almost innumerable cast of D-list celebrities. Easily influenced, I began making jokes around the house about Ishtar, despite the fact that I hadn’t ever seen the film. At the time the film’s lack of merit was so culturally understood that my comments appeared to make sense to anyone older than 20. Soon I thought I would be hitting the stand-up circuit.

The first time I heard of Ishtar was when I was about 13 years old spending a nice summer’s day inside watching television. Elaine May’s comedy starring Dustin Hoffman and Warren Beatty was on the wrong end of various jokes during an episode of VH1’s ever present I Love The 80s. It was labeled stupid, idiotic and everything else by an almost innumerable cast of D-list celebrities. Easily influenced, I began making jokes around the house about Ishtar, despite the fact that I hadn’t ever seen the film. At the time the film’s lack of merit was so culturally understood that my comments appeared to make sense to anyone older than 20. Soon I thought I would be hitting the stand-up circuit.

With the recent appearance of Ishtar on Netflix’s Instant Streaming service and the release of Peter Biskind’s biography on Warren Beatty (Star: How Warren Beatty Seduced America), many will likely take interest, yet again, in the colossal financial failure that was Ishtar. While I was interested in seeing the film I only made it a priority when I saw Roger Ebert’s half-star review from 1987 in which he claimed the film was both “lifeless” and “dreadful.” Ebert punctuated his distaste suggesting that watching the movie unfold was “interesting only in the way a traffic accident is interesting.” What was this traffic accident known as Ishtar that I had made so many blind jokes about? Could it really be that bad?

The answer is quite simple: no (my apologies Mr. Ebert).

Ishtar opens in New York where we meet our two zany protagonists the skittish Lyle Rodgers (Warren Beatty) and the confident Chuck Clarke (Dustin Hoffman). Both have quit their jobs in the hopes of achieving their dreams—becoming successful singer/songwriters. Together they make up the musical duo Rodgers and Clarke, a Simon and Garfunkle rip-off, if Simon and Garfunkle were an 80s band. Rodgers and Clarke spit out inane song after inane song, with little cohesion among their oeuvre. They are certainly no Beatles. Rodgers and Clarke don’t sound just like Simon and Garfunkle, they are also the Beach Boys, the Rolling Stones, Hall and Oates, and Flock of Seagulls; they are electronica, rock, pop and folk. Just never at the same time.

In the hopes of finding success Rodgers and Clarke hire an agent. After a few shows in New York it becomes more than clear the only place the two could have a stable singing career is outside of the U.S. With nothing to lose the two take a gig at the appropriatly named “Chez Casablanca” in the dangerous fictional Middle Eastern country of Ishtar. Overcome by civil unrest, Ishtar is a nation torn by factions trying to overthrow the American puppet regime. As is often the case in Hollywood depictions of the Middle East, danger is around every corner (emphasized by loud speakers continuously repeating that an after dark curfew is in effect). It is inn Ishtar that the film begins to turn into an action-thriller with Rodgers and Clarke getting lost in the confusing world of politics and love.

While the first twenty minutes of the film anticipates the style of humor that Will Ferrell and Adam McKay have made famous, the middle of the movie dives into the standard action-comedy genre. It is in Ishtar that the jokes become rote and the story dull.

But what makes Ishtar interesting is that amidst the overly long chase sequences, and the convoluted and quite frankly stupid plot there is a certain self-awareness of it all. The film establishes the traditional plot arc of white heroes coming to save the day in a foreign land, only to acknowledge that trope and reject it. The unflattering depiction of Arabs is met with an equally unflattering depiction of Americans. Ishtar is a movie about two sad schmucks (or as Lyle pronounces it “smmucks”) living in a world dominated by schmucks. While this doesn’t excuse the film its poor politics, and occasional bad taste (there is one scene where Dustin Hoffman is forced to imitate a Berber, and it culminates in random screaming of vaguely Arabic terms and names such as Kareem Abdul Jabbar) it makes it slightly more bearable.

Towards the end of the film Lyle and Chuck gather up various weapons, which they blindly unload into everything around them: Arab trucks, American helicopters, American jeeps. This is a world where there is little good. Everyone seems to be trying to make a cheap buck or a smart political move. This is perhaps best represented in Charles Grodin’s hilarious portrayal of a C.I.A. Agent Jim Harrison who repeatedly tries to manipulate Chuck. Elaine May’s world is one subsumed by cynicism.

If it is not the complete insanity of the story or the occasionally clever dialogue that is funny, it is the film’s original songs penned by Paul Williams and Elaine May. What starts out as an average pop tune, “Telling the truth can be dangerous business/ honest and popular don’t go hand in hand” slowly devolves into a slightly off-kilter, silly song, “if you admit that you can play the accordion/ no one will hire you in a rock and roll band/ but we can sing!” Actually Mr.Hoffman and Mr. Beatty neither of you can really sing.

The majority of the songs follow this pattern – they are relatable but instantly ridiculous. It is the proximity of Williams and May’s lyrics to those of real songs that make them work so well. Like the songs of Spinal Tap, Ishtar’s soundtrack perfectly straddles the line of being completely outrageous and entirely legitimate.

Ishtar may not be one of the defining comedies of the 1980s but it certainly holds up better than much of that decade’s output. Ishtar is loud, proud and occasionally offensive, but hidden under all of its absurdities lies a glimmer of heart and sincerity. Ishtar was said to have a cost Columbia $55 Million, and it ended up only bringing in about $14 Million at the box office. There was at one time no other word than “failure” to describe Ishtar. The film was certainly a victim of unreachable expectations and hype but perhaps Ishtar was just ahead of its time. Not only is the film not a failure, it is more than just a minor success; Ishtar is funny, farcical and even hypnotic. Perhaps telling the truth (about this film) really can be dangerous business.

I guess this means I have to stop telling those jokes now.

-Nicholas Forster

Ishtar is available on VHS and on Netflix’s Instant Streaming Service. It has also been released on DVD in Europe.

Directed by Elaine May; written by Elaine May; director of photography, Vittorio Storaro; edited by Richard P. Cirincione, Williams Reynolds, Stephen A. Rotter; produced by Warren Beatty; released by Columbia. Running time: 1 hour 43 minutes.

WITH: Warren Beatty (Lyle Rogers), Dustin Hoffman (Chuck Clarke); Isabelle Adjani (Shirra Assel); Charles Grodin (Jim Harrison)

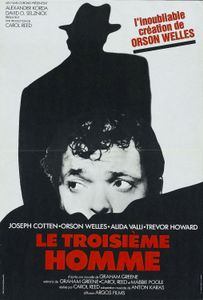

In his Criterion DVD introduction to Carol Reed’s The Third Man, director Peter Bogdanovich explains the stage concept of “Mr. Woo,” also called the “star part.” Here’s how it works: For the first hour of the play, all the characters talk, in hushed voices, about a mysterious fellow named Mr. Woo. “Just wait until Mr. Woo arrives,” they say, and, “Yes, but what will Mr. Woo think?” Mr. Woo dominates the narrative without so much as a cameo. Finally, at the end of the first act, with great dramatic flair, a small figure appears out of the shadows and—my word, it’s Mr. Woo! The curtain falls, and members of the audience remark to each other, “Isn’t the actor who plays Mr. Woo great?” It’s “your reputation precedes you” in action.

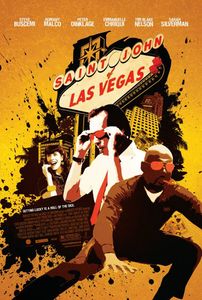

In his Criterion DVD introduction to Carol Reed’s The Third Man, director Peter Bogdanovich explains the stage concept of “Mr. Woo,” also called the “star part.” Here’s how it works: For the first hour of the play, all the characters talk, in hushed voices, about a mysterious fellow named Mr. Woo. “Just wait until Mr. Woo arrives,” they say, and, “Yes, but what will Mr. Woo think?” Mr. Woo dominates the narrative without so much as a cameo. Finally, at the end of the first act, with great dramatic flair, a small figure appears out of the shadows and—my word, it’s Mr. Woo! The curtain falls, and members of the audience remark to each other, “Isn’t the actor who plays Mr. Woo great?” It’s “your reputation precedes you” in action. Let’s get it out of the way from the very beginning: Steve Buscemi needs to be the lead actor in more films. No matter the movie, Buscemi is always interesting to watch and such is the case with St. John of Las Vegas. Starring in a film based on Dante’s Inferno and produced by an interesting collection of artists (most notably Stanley Tucci and Spike Lee) one might just think that St. John of Las Vegas could be an edgy, offbeat, even original film. Yet, while it may be a little quirky, St. John is nowhere close to being edgy. It is so restrained, so held back, that the film verges on being moribund.

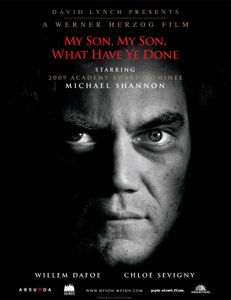

Let’s get it out of the way from the very beginning: Steve Buscemi needs to be the lead actor in more films. No matter the movie, Buscemi is always interesting to watch and such is the case with St. John of Las Vegas. Starring in a film based on Dante’s Inferno and produced by an interesting collection of artists (most notably Stanley Tucci and Spike Lee) one might just think that St. John of Las Vegas could be an edgy, offbeat, even original film. Yet, while it may be a little quirky, St. John is nowhere close to being edgy. It is so restrained, so held back, that the film verges on being moribund. If you had come up to me a year-and-a-half ago, told me that David Lynch was producing a Werner Herzog film and asked me what it was going to be about, “guy kills his mom with a samurai sword to act out Aeschylus’ Oresteia and takes two flamingos hostage” probably wouldn’t have been too far down the list. If you had told me there would be a dwarf in the film, it probably would have been my first choice. I think the surprise would have come if you’d told me that My Son, My Son, What Have Ye Done? would be one of the best things either one of them has ever been involved with. I’ve never been stingy with my praise of Herzog and his work. In my review of Bad Lieutenant: Port Of Call New Orleans (his other surreal , awkwardly titled cop movie from last year, which I’ve been assured was just a coincidence), I called him “almost unquestionably the most influential living European filmmaker after some of the surviving members of the Nouvelle Vague,” a group that sadly shrunk by one recently with the death of Eric Rohmer. I stand by that, and I would like to add that Herzog is also one of the few still pretty routinely putting out great films, as My Son, My Son is his best since Stroszek, and, of the fifteen or twenty of his films that I’ve seen, I honestly believe it would rank third. Herbert Golder, a professor of classics at BU and the film’s co-writer, presented the film and mentioned, among other things, that Herzog considered this an intensely personal film and preferred it to the more studio-driven Bad Lieutenant. Of course, Herzog is right to do so; it is the better film.

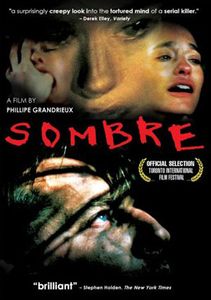

If you had come up to me a year-and-a-half ago, told me that David Lynch was producing a Werner Herzog film and asked me what it was going to be about, “guy kills his mom with a samurai sword to act out Aeschylus’ Oresteia and takes two flamingos hostage” probably wouldn’t have been too far down the list. If you had told me there would be a dwarf in the film, it probably would have been my first choice. I think the surprise would have come if you’d told me that My Son, My Son, What Have Ye Done? would be one of the best things either one of them has ever been involved with. I’ve never been stingy with my praise of Herzog and his work. In my review of Bad Lieutenant: Port Of Call New Orleans (his other surreal , awkwardly titled cop movie from last year, which I’ve been assured was just a coincidence), I called him “almost unquestionably the most influential living European filmmaker after some of the surviving members of the Nouvelle Vague,” a group that sadly shrunk by one recently with the death of Eric Rohmer. I stand by that, and I would like to add that Herzog is also one of the few still pretty routinely putting out great films, as My Son, My Son is his best since Stroszek, and, of the fifteen or twenty of his films that I’ve seen, I honestly believe it would rank third. Herbert Golder, a professor of classics at BU and the film’s co-writer, presented the film and mentioned, among other things, that Herzog considered this an intensely personal film and preferred it to the more studio-driven Bad Lieutenant. Of course, Herzog is right to do so; it is the better film. Verite camerawork has been a major force in the modern horror film, but to mixed success at best. I always hoped that somewhere out there, someone had gotten it right. That someone was Philippe Grandrieux. He did it back in 1998, a year before Blair Witch made the technique into a style, with his film Sombre. To be fair, I can only call it a horror film because it certainly isn’t anything else, and I guess it does fit best into that genre. There are no people jumping out of the darkness and there is no gore, but there is an all-enveloping sense of doom that permeates every single frame. What separates the film from others of the type is that Grandrieux doesn’t create his mood through the disorientation inherent to handheld camerawork, but instead through lighting and focus. The title is, in a way, kind of a joke as “somber” barely even begins to describe this work, but I guess Misery was already taken and “sombre” also translates to “darkness,” which fits perfectly. This is a dark film in every sense of the word and even many of the film’s brightest shots are out of focus, as if the director wants to call the audience into the prevailing darkness. This lack of light does something vital to the film as a whole. It takes people and objects and turns them into abstract forms on a means eerily reminiscent of Brakhage. Grandrieux appears to have a rare talent for pulling something vital out of every image in his film. All those vital little images come together to form one of the greatest horror films of all time.

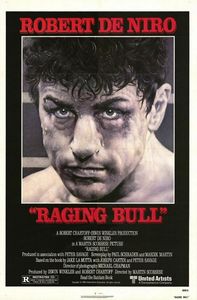

Verite camerawork has been a major force in the modern horror film, but to mixed success at best. I always hoped that somewhere out there, someone had gotten it right. That someone was Philippe Grandrieux. He did it back in 1998, a year before Blair Witch made the technique into a style, with his film Sombre. To be fair, I can only call it a horror film because it certainly isn’t anything else, and I guess it does fit best into that genre. There are no people jumping out of the darkness and there is no gore, but there is an all-enveloping sense of doom that permeates every single frame. What separates the film from others of the type is that Grandrieux doesn’t create his mood through the disorientation inherent to handheld camerawork, but instead through lighting and focus. The title is, in a way, kind of a joke as “somber” barely even begins to describe this work, but I guess Misery was already taken and “sombre” also translates to “darkness,” which fits perfectly. This is a dark film in every sense of the word and even many of the film’s brightest shots are out of focus, as if the director wants to call the audience into the prevailing darkness. This lack of light does something vital to the film as a whole. It takes people and objects and turns them into abstract forms on a means eerily reminiscent of Brakhage. Grandrieux appears to have a rare talent for pulling something vital out of every image in his film. All those vital little images come together to form one of the greatest horror films of all time. Martin Scorsese’s Raging Bull is often called a “boxing movie,” and grouped alongside the likes of Rocky in discussions of such things. The American Film Institute, for its part, proclaimed it the No. 1 sports movie of all time. The label is erroneous. Raging Bull concerns itself with many things, but sports is not chief among them.

Martin Scorsese’s Raging Bull is often called a “boxing movie,” and grouped alongside the likes of Rocky in discussions of such things. The American Film Institute, for its part, proclaimed it the No. 1 sports movie of all time. The label is erroneous. Raging Bull concerns itself with many things, but sports is not chief among them. There are perhaps few directors whose films have suffered as much as John Ford’s have in the transition of big screen to televisions. While the politics can be oppressively conservative Ford’s films, without question, always look beautiful. It is this beauty that defines the current series at the MFA running right now, The Making of the Western Myth. Using Monument Valley as an emblem of the west, Ford created a cannon of ten films, all shot in Monument Valley, which came to define the Western.

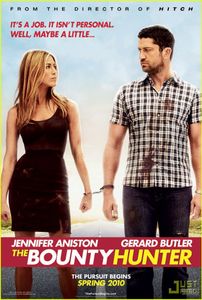

There are perhaps few directors whose films have suffered as much as John Ford’s have in the transition of big screen to televisions. While the politics can be oppressively conservative Ford’s films, without question, always look beautiful. It is this beauty that defines the current series at the MFA running right now, The Making of the Western Myth. Using Monument Valley as an emblem of the west, Ford created a cannon of ten films, all shot in Monument Valley, which came to define the Western. As I sat on the Green Line on my way to the screening of Andy Tennant’s The Bounty Hunter, I thought I knew exactly what I was going to see. In fact, I even began writing this review in my head. However, I was pleasantly surprised. Sure, there was the obvious scene or cliché joke here or there, but ultimately the film is a contemporary screwball comedy, a modern-day His Girl Friday, with a twist of course.

As I sat on the Green Line on my way to the screening of Andy Tennant’s The Bounty Hunter, I thought I knew exactly what I was going to see. In fact, I even began writing this review in my head. However, I was pleasantly surprised. Sure, there was the obvious scene or cliché joke here or there, but ultimately the film is a contemporary screwball comedy, a modern-day His Girl Friday, with a twist of course. L&S: Are there limitations or aspects that force you to sometimes change a design? (I'm thinking Downhill Racer as one specific, but I'm sure there are others.)

L&S: Are there limitations or aspects that force you to sometimes change a design? (I'm thinking Downhill Racer as one specific, but I'm sure there are others.)

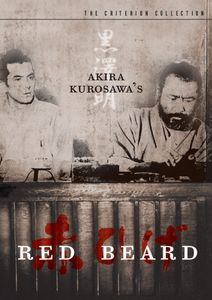

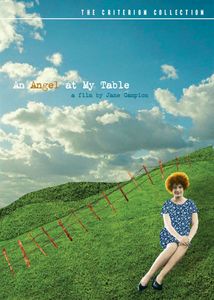

L&S: Was there a specific reason why the cover for Angel was rejected?

L&S: Was there a specific reason why the cover for Angel was rejected? L&S: Can you talk about The Bad Sleep Well and the balance of minimalism and detail in your work?

L&S: Can you talk about The Bad Sleep Well and the balance of minimalism and detail in your work? L&S: And the obligatory question about advice for future designers?

L&S: And the obligatory question about advice for future designers?