This semester, I – Laura Masur – conducted an educational research project as part of a Teaching as Research (TAR) fellowship, sponsored by the Center for the Integration of Research, Teaching and Learning (CIRTL) at BU. The overarching goal over this program is to teach young academic professionals in STEM fields to be better teachers, using the scientific research process. While archaeology’s place in STEM is undoubtedly up for debate, this was a great opportunity for me to start thinking about the mechanics of teaching. The program provides excellent opportunities to explore recurring trends in classes, in order to improve student learning outcomes.

View Poster: 2016.5.2_TAR_Poster_FINAL

View Poster: 2016.5.2_TAR_Poster_FINAL

Archaeology professors at BU have observed that students in 300-level classes have difficulty developing research questions and testable hypotheses. Students also encounter problems when connecting technical methods (e.g., the identification and analysis of animal bones) to their broader historical or cultural context in order to draw conclusions from research. This was particularly reflected in final written research reports in AR 308, Archaeological Research Design and Materials Analysis, taught by Catherine West. Others have observed that many archaeology students lack the necessary scientific background for reading primary literature and developing their own research projects (Agbe-Davies et al. 2013:839). Journal club workshops that providing students with the necessary skills for reading and analyzing journal articles have been shown as effective methods for teaching scientific literacy in a classroom setting (Robertson 2012).

For this project, I investigated whether teaching scientific literacy to students using journal articles would more effectively prepare them to develop and carry out independent research projects. Students completed pre-tests and post-tests in the form of journal worksheets (adapted from Robertson 2012), and submitted their own research design in a similar format. Students were also asked to complete an anonymous survey about their experiences learning about research design in the class. I hypothesized that if students are able to develop scientific literacy through reading and evaluating journal articles, they will be able to more readily generate their own research questions and hypotheses, and as a result, more effectively connect their data to broader research themes.

Sample worksheet completed by students as a pre-test and post-test for determining scientific literacy (View Worksheet: 308_Worksheet_1 ).

Sample worksheet completed by students as a pre-test and post-test for determining scientific literacy (View Worksheet: 308_Worksheet_1 ).

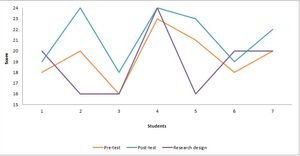

The results of the project surprised me. Post-test values were slightly higher than pre-test values, meaning that students’ ability to read and gather key information from articles increased after related lessons, and the difference between these values was statistically significant (p < .05) when using a paired t-test. Nonetheless, the results of the post-test and the research design were not well correlated (r = .43), suggesting that students who did well on journal article assignments did not always succeed to the same degree when creating their research design. This suggests that learning about research design through related reading (e.g., Booth et al. 2008), primary literature, and class discussion is not sufficient to prepare all students to generate their own research questions and hypotheses.

Line graph showing pre-test, post-test, and research design scores, with slight correlation (n = 7, max score = 24).

Line graph showing pre-test, post-test, and research design scores, with slight correlation (n = 7, max score = 24).

Students had neutral to positive reactions to the article worksheet, suggesting that it may serve as a useful learning tool in future classes. Students also agreed that reading primary literature prepared them to develop their own research design, which indicates the importance of this exercise. Additional in-class activities may provide an avenue for students to improve their ability to develop scientific research designs. Future research may establish whether in-class activities, which would guide a student through the process of developing a research design, would help students by simulating the research process. Students could be provided with a research scenario, and work in groups to develop a research design, which they would then present to the class.

References cited

Agbe-Davies, Anna S., Jillian E. Galle, Mark W. Hauser, and Fraser D. Neiman. 2013. “Teaching with Digital Archaeological Data: A Research Archive in the University Classroom.” Journal of Archaeological Method and Theory 21 (4): 837–61.

Booth, Wayne C, Gregory G Colomb, and Joseph M Williams. 2008. The Craft of Research. Third edition. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Robertson, Katherine. 2012. “A Journal Club Workshop That Teaches Undergraduates a Systematic Method for Reading, Interpreting, and Presenting Primary Literature.” Journal of College Science Teaching 41 (6): 25–31.

Students Ryan, Kate, Alexandria, Rachel, and Professor

Students Ryan, Kate, Alexandria, Rachel, and Professor

Student Rachel Gill mid-excavation

Student Rachel Gill mid-excavation

Block B just after the sod and Katmai ash was removed

Block B just after the sod and Katmai ash was removed Alutiiq Museum intern Jesse kneeling next to

Alutiiq Museum intern Jesse kneeling next to Students Alexandria and Jeannine excavate the

Students Alexandria and Jeannine excavate the Student Rachel crouches in the extended smoke pit - note the charcoal-rich L1Ag at her feet, and the 3800-year old ash fall (L2) that covered the pit.

Student Rachel crouches in the extended smoke pit - note the charcoal-rich L1Ag at her feet, and the 3800-year old ash fall (L2) that covered the pit.

Example of the stratigraphy found at Salonie Creek, Kodiak Island - note the thick 1912 Katmai volcanic ash at the top, covering the archaeological layers below.

Example of the stratigraphy found at Salonie Creek, Kodiak Island - note the thick 1912 Katmai volcanic ash at the top, covering the archaeological layers below. Bayonet shaft used for hunting sea mammals - this is made of ground slate, which is common in the area around the Kashevaroff site.

Bayonet shaft used for hunting sea mammals - this is made of ground slate, which is common in the area around the Kashevaroff site. Ground slate point - the lines may be the hunter's identifying mark!

Ground slate point - the lines may be the hunter's identifying mark! Red chert stone tool from the Kachemak period - this is probably a small knife that would have been hafted into a bone handle.

Red chert stone tool from the Kachemak period - this is probably a small knife that would have been hafted into a bone handle. Example of a microblade from the Ocean Bay I period

Example of a microblade from the Ocean Bay I period