Artistic Representation of the Female Gender from the Renaissance to the Enlightenment

Katryna Santa Cruz

Tintoretto, Susanna and the Elders, 1555-6; Wikipedia

Introduction

Art is a product of its time. It is a result of the social, political, and religious context in which it was made. Because of its consequential nature, it has become the center of focus for historians interested in revisionist theories about the representation of its subjects. This research guide has compiled sources of information that lend itself to a research paper on the representation of women in art history. The sources in this research guide form connections between art and history to provide arguments for or against the idea of a factual representation of women in art.

The guide consists of a General Overview section with sources that cover a broad sense of the representation of women in art in several art periods but focusing on Victorian Art, Renaissance Art, and Art of the Enlightenment. Other sections in this research guide include Representation of Rape in Art History, Women in Religious Art and Imagery, Gender Neutrality in Art, Gender Differences in Art, and Sexuality and Eroticism in Art.

Manet, Olympia, 1865; Wikipedia

General Overview

In Feminism and Art History: Questioning the Litany, authors Norma Broude and Mary Garrard place art production in social context. Through several essays, the authors show how the social, political, and religious circumstances of different art periods affect the way women were represented. Feminism and Art History includes a wide range of art periods including Egyptian Pharaoh Art, Roman Art, Medieval Art, 18th and 20th-century art and concludes with American quilts. The authors spread the content of the essays among different regions in Europe which I feel is essential to a study on the representation of women in art as it lends itself as an enciclopediac-like source for all of Europe, rather than just one country or region.

I feel this source is critical in doing research on the representation of women in art as it offers variety in content relative to the thesis, extensive evidence to support its arguments, and a generally unbiased presentation of information as it seeks to create a new art history rather than simply working with the modern version.

Broude, N. & D Garrard, M. Feminism and Art History: Questioning the Litany. New York: Harper & Row, 1982.

The sequel to Feminism and Art History: Questioning the Litany, The Expanding Discourse: Feminism and Art History presents an even more influential source of information as it aims to expand the knowledge delivered in Feminism and Art History to art outside of Western culture. Written in the same style, a compilation of essays, The Expanding Discourse begins in Early Renaissance culture and paves a new path of art history through the critiques of works by Botticelli, Rubens, Degas, Gauguin, Kahlo, O’Keeffe, and many other iconic artists.

Although this sequel is heavily shaped by feminist theories, creating a somewhat biased presentation of information, I believe the authors were more effective in setting the sociopolitical context. Without inserting gender theories, ones relevant to the time when the art was created, their thesis would have become out of context and their arguments would have lessened in relevance and influence. Although the majority of this book focuses on post-Renaissance art, I feel it is important in conducting research on the representation of women in art as it touches upon subjects that were not discussed in the prequel including sexual violence, lesbianism, and early feminism (all during or before the Renaissance).

Bourde, N. & D Garrard, M. The Expanding Discourse: Feminism and Art History. Boulder, CO: Westview Press, 1992.

Paola Tinagli gives a general overview of women as subject-matter in Italian Renaissance painting. I believe this is an essential source of information as the author places a heavy focus on one of the key concepts in studying art history; the relationship between the patron and the artist. Most subject-matter in Renaissance Art is a direct product of this relationship and no art history critique is complete without consideration of it. The author’s evidence for these relationships are found in letters, poems, and treatises that she revises herself, rather than the use of the already established art historical stories.

Tinagli, P. Women in Renaissance Art: Gender, Representation, Identity. Manchester, England: Manchester University Press, 1997.

Lynda Nead’s The Female Nude: Art, Obscenity, and Sexuality seeks to find why the female nude has become an icon of Western culture. The prevalence of images of the female body in the history of Western art has begun to tie the female nude to an ‘art’ connotation, even in modern art. Nead discusses the dissemination of the ‘high art’ female nude in art education and supports her argument by using art publications and the language of art criticism itself to bring together an entirely new analysis of the historical tradition of female nudes in art. Although The Female Nude attempts to discover the reason for the trend, I felt this source can provide evidence of early nudes in art pertinent to the age periods for which this research guide is catered to.

Nead, L. The Female Nude: Art, Obscenity, and Sexuality. London: Routledge, 1992.

In this short essay, Saylor Academy offers a compact look at the effects of 15th-18th century European society on the representation of women in art. They offer concise summaries regarding women’s status in society, Dual Representations of Women During the Renaissance, Effects of the Protestant and Catholic Reformation on Women, and Women and the Enlightenment.

As the author explores, women didn’t have a voice in their communities regarding economics or politics. Their most important job was to be a mother and wife, before being a woman. As the Enlightenment pervaded the European society, “women began to take advantage of new intellectual trends.” The author then discusses dual representations of women during the Renaissance — a complex developed by Sigmund Freud called “the Madonna-Whore complex” where men see women as either Madonnas or whores. As the author explains, figures of the Renaissance represented women as they were in seen in their times — “as either virtuous and chaste or seductive and deceptive.” Effects of the Protestant and Catholic Reformation on Women explores the idea of the patriarchy (and in turn, the Church, the most powerful political force of the time) controlling women in a way that led to their discrimination and persecution throughout Europe and North America (using the Salem Witch Trials as an example). Women and the Enlightenment explores women and their involvement in salon culture and literature. Although this essay doesn’t provide any specific artistic examples of the representation it discusses, it does provide social, political, and religious reasons for why Renaissance art represents women the way it does.

“Women From the Renaissance to the Enlightenment.” Saylor Academy. January 1, 2014. Accessed November 13, 2014. http://www.saylor.org/site/wp-content/uploads/2012/10/HIST201-8.2.3-WomenRenaissancetoEnlightenment-FINAL1.pdf.

This source, although in an informal format, provides numerous links that represent the most common trends in Victorian Art (late 19th century). These categories include Female Power (e.g. goddesses, femme fatale, monster women, etc.), Female Powerlessness – Woman as Victim (e.g. women in chains, martyrs, fallen women, etc.), Objects of Desire (e.g. the adoring woman), Women as Ideal (e.g. madonnas and mothers), and Miscellaneous (e.g. servants and governesses).

I find this source to be a healthy complementary to the previous source (Women From the Renaissance to the Enlightenment) as it offers a visual representation of the reasons that Women From the Renaissance to the Enlightenment delivered for the representation of women in art, although this source focuses on a later art period. Some of the links in this source lead to essays digressing into each of the topics while other links provide a wide array of paintings, symbols, and illustrations that fall under each category (Female Power, Woman as Victim, etc.).

“Women as Subject in Victorian Art — Representations of Women.” Victorian Web. July 13, 2009. Accessed November 13, 2014. http://www.victorianweb.org/gender/arts2.html

Representation of Rape in Art History

From Victim to Victor is the fourth part of a seven-part essay series written by Roger Denson covering topics in art history ranging from gender performance to gender divides. The writer aims to develop a discourse concerning the representation of rape in art. I believe the most interesting part of this essay is the fact that he addresses the time differences in the art he critiques. He is well aware that most historical rape scenes are a product of male artists while the pivotal, modern rape scenes are a product of female artists. Taking this into consideration, Denson takes a look at the “dramatic differences between the artistic tenors and depicted ethical values of men and women, ancients and moderns, that we can discern how and why rape not only persists at such a high incidence in civilization, but as well how visual representations factor into this persistence.”

Although Denson places a heavy focus on modern art made by female artists, he does provide substantial evidence to support his comparison; thereby lending itself effectively to a research paper on the representation of women in historical rape scenes.

Denson, G. Roger. “From Victim to Victor: Women Turn the Representation of Rape Inside Out.” Huffington Post. November 11, 2007. Accessed November 12, 2014. http://www.huffingtonpost.com/g-roger-denson/facing-the-interior-and-t_b_1073672.html

Botticelli, Primavera, 1482; Wikipedia

Diane Wolfthal’s Images of Rape: The ‘Heroic’ Tradition and Its Alternatives can become a very influential source of information if used in a research paper focused on the representation of women through rape scenes in art history. Wolfthal’s main thesis is to address the “heroic” act of rape, as depicted in art history. She does this by dividing the book in two sections: “the first section will examine how these [rape scenes] glorify, sanitize, and aestheticize sexual violence; the second section will investigate how art historians have reinforced this construction.” In a salient, revisionist tradition, Wolfthal breaks down the most inflentual works of art depicting rape scenes and provides a range of visual documentation, including pictorial Bible scenes, law treatises, history paintings, war prints, and the manuscripts of Christine de Pizan, a Medieval author who was arguably one of the first persons to ever write about women’s rights.

Wolfthal, D. Images of Rape: The ‘Heroic’ Tradition and Its Alternatives. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1999.

Women in Religious Art and Imagery

Haulage Augen – und Gemüthslust, Augsburg, Charity as Holy Spirit, 1706; Representation of Women in Religious Art and Imagery.

The Representation of Women in Religious Art and Imagery is a chapter in Gender in Transition: Discourse and Practice in German-Speaking Europe, 1750-1830. Written by Stefanie Schäfer-Bossert, this chapter covers the slow disappearance of women in religious imagery and the disparity in gender representation in religious art: “one depicts the male in the historical present and legitimizes him through his profession and his social prestige; the other makes women appear ahistorical by means of mythological metaphor.”

Although concise, Schäfer-Bossert provides enough imagery and evidence to support her argument. She uses a wide variety of resources, herself, in writing this chapter; she uses theories developed by theological gender studies scholars, forms her own theories from imagery seen in chapels around Europe, and provides the reader with a clear timeline of events that supports her thesis.

Schäfer-Bossert, S. Gender in Transition: Discourse and Practice in German-Speaking Europe, 1750-1830: The Representation of Women in Religious Art and Imagery. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press, 2006.

Part of The Jewish Women’s Archive‘s Featured Collection on Feminism, Art: Representation of Biblical Women, is an extensive compilation of research comparing the portrayals of women in biblical stories among Christian and Jewish biblical texts. An alternate approach to the portrayals of women provided in the rest of this guide, Mati Meyer takes a cross-religious look at how the social implications brought on by religious communities affected the art it produced. As Meyer points out, because “in early Christian and medieval art the image of biblical women served primarily to emphasize a typological meaning,” I found it essential that this essay be a part of this research guide as art reflects society just as much as society reflects its art.

Meyer, M. “Art: Representation of Biblical Women.” Jewish Women’s Archive. March 20, 2009. Accessed on December 8, 2014. http://jwa.org/encyclopedia/article/art-representation-of-biblical-women

Gender Neutrality in Art

.jpg)

Géricault, Raft of the Medusa, 1818; Wikipedia

Linda Nochlin’s Géricault, or the Absence of Women is an essay published in the Spring 1994 edition of October, a journal at the forefront of contemporary arts critique and theory. As the title suggests, Géricault, or the Absence of Women looks at one artist in particular, Théodore Géricault, and the portrayal of femininity in his work, or rather the lack thereof.

Although quite specific in content, I find this source to be essential to this research guide as Nochlin’s methodology in critiquing Géricault’s work can be used when looking at other artworks from the same art period.

Nochlin, L. “Géricault, or the Absence of Women.” October, Vol. 68, Spring, 1994, pp. 45-59. Accessed December 1, 2014. MIT Press. http://www.jstor.org.ezproxy.bu.edu/stable/10.2307/778696?origin=crossref

Part five of Roger Denson’s seven-part essay series, Did Men Invent Art to Become Women? Must Women Become Men to Make Great Art? Although very biased in content, as to support his argument, Denson provides examples of art pieces that portray women in a gender-neutral state. This source provides variety to this research guide as it presents a new portrayal of women in art history — not that of a victim or a femme fatale (always imposing the female gender), but rather lacking the things that make her a woman and not yet a man.

Denson, R. “Did Men Invent Art to Become Women? Must Women Become Men to Make Great Art?” Huffington Post. January 20, 2012. Accessed November 30, 2014. http://www.huffingtonpost.com/g-roger-denson/did-men-invent-art-to-bec_b_1218788.html

Gender Differences in Art

These sources, using examples of both genders in art history, give a different perspective on the way revisionist historians look at the representation of women. By critiquing the way men are portrayed, a conclusion can be drawn by contrasting the portrayal of women.

Art History Webmasters Association

Noted as an an illustrated lecture for a Bluffton College Forum, Oh What a Difference Gender Makes: Gender in the Visual Arts, is one of the most informal sources of information pertinent to this research guide. Although Mary Ann Sullivan provides the reader with many examples to prove her point, she does so in a quick manner, leaving the art to support her argument rather than the writing itself. The series includes essays on: Gender Definitions in Portraits, Depictions of Male and Female Nudes, Depictions of Motherhood and Fatherhood, Gendered Working Roles, and Critiques of Gender Roles.

I felt this was essential for sources and because it compares both genders, rather than just one, despite the title,

Ann Sullivan, M. “Oh What a Difference Gender Makes: Gender in the Visual Arts.” Bluffton.edu. 2002. Accessed on November 23, 2014. http://www.bluffton.edu/~sullivanm/forum/gender.html

Roger Denson’s XX Chromosocial, Part 1: Women’s Hidden Homosocial Past can be summarized in one sentence:

“It’s through art history that we see what contemporary art can only suggest: how art over time promotes cultural codes, and as part of its historicizing and status-raising functions–the very functions that make art attractive to the affluent and powerful–art normalizes and perpetuates the specific conventions for a society’s arrangement of sex and gender relations and the objects accorded them by the requisites of the dominant homosocial order.”

In this source, Roger Denson takes a look at homosocial order in history, as portrayed by art. The author takes examples from pre-historic, Renaissance and post-Renaissance art to show just how factual is the representation of gendered activities in art history. I’ve decided to include this source in this research guide because I feel Denson supports his arguments with heavy amounts of examples and provides a research paper on the representation of women in art with an angle that has not been reached by the other sources in this guide.

Denson, R. “XX Chromosocial, Part 1: Women’s Hidden Homosocial Past.” Huffington Post. March 8, 2011. Accessed November 30, 2014. http://www.huffingtonpost.com/g-roger-denson/xx-chromosocial-women-art_b_832867.html

Sexuality and Eroticism in Art

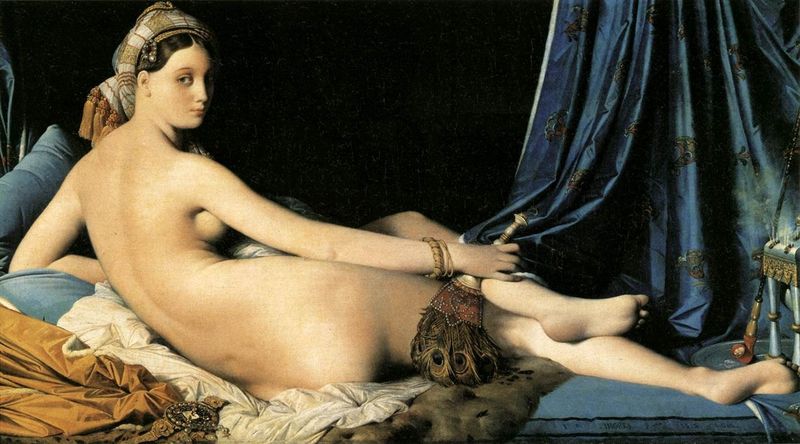

Ingres, La Grand Odalisque, 1814; Wikipedia

Edward Lucy-Smith’s Sexuality in Western Art is a comprehensive look at portrayals of sexuality in art. The book starts with pre-historic art and places a heavy focus on art of the Renaissance. He considers the traditions in society and the time the art was made and compares them to symbols in the artwork.

Lucy-Smith, E. Sexuality in Western Art. Thames & Hudson Ltd, 1991.

Sexuality: An Illustrated History is a pictorial history of sexuality in Western art. The book covers art periods ranging from the Middles Ages to contemporary art. Sander Gilman’s reason for starting his study in the Middle Ages is that he uses the early roots of Christianity to trace myth-making about the sexual form through art, literature, anatomy, and medicine. In using Christianity as a guideline of sorts for Sexuality: An Illustrated History, Gilman provides evidence to show how cultures are self-defined and shaped by systematic concepts of beauty and ugliness, masculinity and femininity, health and sickness, and the sacred and the secular and how these concepts have remained prevalent for nearly two millennia.

Although this book doesn’t always use art as visual evidence, I believe it’s use of Christian art, specifically, caters to a research paper on the representation of women in art pertinent to the Renaissance Period as it is the culmination of Christian art.

Gilman, S. Sexuality: An Illustrated History. New York: John Wiley and Sons, Inc., 1989.

Related Sources

Although informal in format, The Art History Archive remains a fairly thorough resource of information on artworks, art periods, artists, critiques, art by country/culture, and art history.

The video below provides visual context of most of the nudes aforementioned in the previous sources:

I’ve included the video below as some of the aforementioned sources compare female nudes to male nudes, also providing visual context to the research guide: