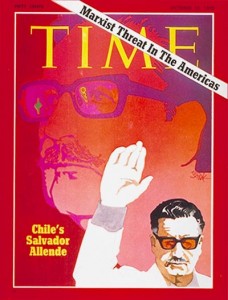

Left: East German stamp proclaiming solidarity with Allende; unknown source, accessed from Wikimedia Commons. Right: Magazine cover on Allende’s election; accessed from Time Magazine‘s website.

INTRODUCTION

The purpose of this study guide on the Chilean revolution and counterrevolutionary movements in the 1970s was to explore a lesser known but no less important example of revolution in the 20th century. The revolution in Chile saw the first democratic election of a Marxist leader in the Western Hemisphere, an election which inspired hope for some and spelled disaster for others. This leader, President Salvador Allende, promised socialism “La vía chilena” (the Chilean way): “political, social, and economic transformation legally [done], through established Chilean institutions; and he would achieve the transition without violence, without the dictatorship of the proletariat, and without the millions of deaths experienced elsewhere when the road to socialism was traversed by force,” (Davis iv). A complicated and frequently chaotic battle ensued as Allende, his party Unidad Popular, and their supporters attempted to enact socialist policies to take back the land and resources held in the hands of the few. A strong opposition fomented among Chileans across classes, in the military, and abroad as the United States, embattled in the Cold War, sought to maintain its hegemonic influence in Latin America and the Western Hemisphere. The Chilean revolutionary experiment met its end on September 11th, 1973, when counterrevolutionary forces coalesced in a military coup that toppled the longest standing democracy on the South American continent. Allende died with his revolution, as did many others after Augosto Pinochet’s military dictatorship seized power.

The sources gathered here, from both the past and present, demonstrate no neutral feelings about Compañero Presidente Allende and his revolution. Observers and analysts, like the participants in the events themselves, tend to either lionize or demonize Allende, Nixon, Kissinger, and the rest. The guide begins with selected primary sources capturing various perspectives of the revolution, both internal and external. These include interviews with workers and women in Chile, with land-takers and land owners, memos from Kissinger on Chile and his later commentary in a memoir, and words from Allende himself. The second part of the guide contains secondary sources from historians, political scholars, and a documentarian. These sources exemplify the controversy that still surrounds the Chilean revolution today as different authors emphasize different causes for the downfall of the revolution and the Allende regime.

j

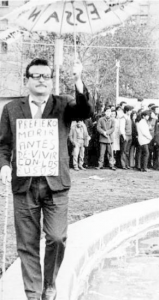

Chileans supporting Allende’s candidacy, 1964.

Photograph by James N. Wallace, accessed from Wikimedia Commons.

k

PRIMARY SOURCES

THE CHILE READER-

Hutchison, Elizabeth Quay, Thomas Miller Klubock, and Nara B. Milanich, eds. “The Chilean Road to Socialism: Reform and Revolution.” Latin America Readers: Chile Reader: History, Culture, Politics. Durham, NC: Duke University Press Books, 2013. p.343-428. Accessed November 10, 2015. ProQuest ebrary.

This book (in the chapter cited here) contains a plethora of relevant primary sources about the Chilean revolution and counterrevolution from many different perspectives of involvement. The sources in this chapter offer insight into the factors that lead to Allende’s election and the causes for his revolution’s failure. The first sources in this chapter characterize the period of reform in the 1960s that preceded Allende’s election. Then there are sources describing Allende’s and the socialists’ goals for democratic revolution in Chile. Following this, there are the sources that demonstrate the factors working against Allende’s revolution and the causes for counterrevolution. In addition to external causes for counterrevolution, this chapter importantly offers insight into the internal dimension as well: “The tensions between the phased and controlled revolution from above and the more spontaneous and locally informed revolution from below were never resolved, constituting a fatal flaw in the Chilean revolutionary process,” (348). In this way, the editors offer a balanced resource on a controversial topic. I have listed selected documents from The Chile Reader below.

Property and Production: A Pamphlet Promoting Christian Democracy’s Agrarian Reform. Translated by Ryan Judge. 1966. In The Chile Reader: History, Culture, Politics. Edited by Elizabeth Quay Hutchinson, Thomas Miller Klublock, and Nara B. Milanich, 356-61. Durham, NC: Duke University Press Books, 2013. Accessed November 1, 2015. ProQuest ebrary.

In the 1960s, the Christian Democrats held power under the president Eduardo Frei and enacted a number of reform policies to improve standards of living and inequality in Chile. This is a pamphlet from the Christian Democrat Party discussing agrarian reform during this time. The authors of the pamphlet contrast the productive capacity of Chile through figures on unused land and jobless poor with the current unequal situation. They give many figures on the inequity of land ownership in Chile and discuss urbanization and overcrowding as a growing problem in Chile. The authors portray land reform as a means to improve living conditions of the peasant classes and improve the welfare of the entire nation without hurting the land owning classes. The address of landowners is notable because the supporters of the Christian Democrat Party were primarily from the middle and upper classes.

The Election of 1970. In The Chile Reader: History, Culture, Politics. Edited by Elizabeth Quay Hutchinson, Thomas Miller Klublock, and Nara B. Milanich, 376-79. Durham, NC: Duke University Press Books, 2013. Accessed November 1, 2015. ProQuest ebrary.

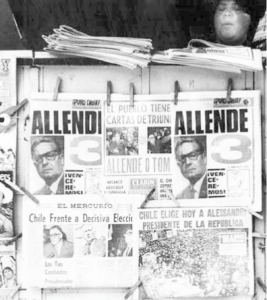

This chapter contains three images (pictured below) from the election of 1970, demonstrating how contentious the election was and how politicized the electorate in Chile had become. The first image shows young people painting murals in support of Allende. The center and left campaigns engaged people through art, music, and street rallies during the election of 1970. The second photo demonstrates the fears the right and its supporters held concerning Allende and the possible election of a Marxist. The man in the photo wears a sign that says, “I would rather die than live with the Russians,” expressing the common fear held by conservatives that Allende’s election would mean the end of democracy and freedom and the coming of Communism. The third image of newspapers speculating the outcome of the election shows how uncertain and how close the election was in Chile.

Kissinger, Henry A. Memorandum, “Memorandum for the President,” November 5, 1970. In The Chile Reader: History, Culture, Politics. Edited by Elizabeth Quay Hutchinson, Thomas Miller Klublock, and Nara B. Milanich, 381-383. Durham, NC: Duke University Press Books, 2013. Accessed November 1, 2015. ProQuest ebrary.

In this memo from former Secretary of State Henry Kissinger (then National Security Advisor) to President Richard Nixon, he discusses the relevance of the 1970 election in Chile to the United States. He claims that the election of Allende in Chile will affect the U.S. position against the Soviet Union, in the Western Hemisphere, and in the world. He asserts that Allende has a “profound anti-U.S. bias” and will seek to eliminate U.S. influence in Latin America and strengthen the influence of communist states there. Importantly, he notes that Allende was democratically elected and therefore the legitimate leader of Chile in the eyes of the nation and the world. To that end, he says, “We are strongly on the record in support of self-determination and respect for free elections; you are firmly on record for non-intervention in the internal affairs of this hemisphere…. It would therefore be very costly for us to act in ways that appear to violate those principles,” (382). However, should Chile act as a “model” for the rest of Latin America and the world, the effect would be “insidious,” (383).

Kissinger, Henry A. Memorandum, “National Security Decision Memorandum 93,” November 9, 1970. In The Chile Reader: History, Culture, Politics. Edited by Elizabeth Quay Hutchinson, Thomas Miller Klublock, and Nara B. Milanich, 383-85. Durham, NC: Duke University Press Books, 2013. Accessed November 1, 2015. ProQuest ebrary.

This is a second memo form Kissinger to the Secretary of State, the Secretary of Defense, and to the head of the CIA on a meeting to decide what to do about Chile just after the election of Salvador Allende. According to Kissinger’s memo, President Nixon ordered that U.S. assume a “correct but cool” diplomatic posture towards Chile and that the U.S. will pressure the Allende government to limit its capability to carry out policies “contrary to U.S. and hemisphere interests,” (383). The U.S. should furthermore, “maintain close relations with friendly military leaders in the hemisphere,” (384). He also notes plans to end monetary aid and capital financing to Chile, an economic policy that came to be known as the “invisible blockade” which gravely affected the Chilean economy during the Allende years.

Ailío, Don Heriberto, Doña Marta Antinao, Violeta Maffei de Landarretche, and Luciano Landarretche. “The Mapuche Land Takeover at Rucalán: Interviews with Peasants and Landowners.” By Florencia Mallon, 1977. In The Chile Reader: History, Culture, Politics. Edited by Elizabeth Quay Hutchinson, Thomas Miller Klublock, and Nara B. Milanich, 386-92. Durham, NC: Duke University Press Books, 2013. Accessed November 1, 2015. ProQuest ebrary.

These documents on the “revolution from below” reflect an important dimension of the Chilean revolution. Chile’s revolution is especially notable because revolutionaries worked within the existing governmental institutions and took power democratically. In these documents, we see the undemocratic elements of the socialist revolution as there were leftist groups using force to bring forth revolution in the country. It is important not to ignore this element as it lead to later problems for the Allende government: “The tensions between the phased and controlled revolution from above and the more spontaneous and locally informed revolution from below were never resolved, constituting a fatal flaw in the Chilean revolutionary process,” (348). The speakers in this interview recount both the peasant takeover of the Rucalán holding and the attempt to reclaim the land by the owners. While the peasants saw the takeover as reclaiming the land that had been illegally taken from their native ancestors by invaders, the landowners considered Rucalán their property taken by violent delinquents.

Workers march celebrating the nationalization of the Yarur cotton mill.

Photograph by Peter Winn, accessed from The Chile Reader.

k

“Revolution in the Factory: Interviews with Workers at the Yarur Cotton Mill.” By Peter Winn, 1986. In The Chile Reader: History, Culture, Politics. Edited by Elizabeth Quay Hutchinson, Thomas Miller Klublock, and Nara B. Milanich, 393-99. Durham, NC: Duke University Press Books, 2013. Accessed November 1, 2015. ProQuest ebrary.

This source too demonstrates the conflict between the workers’ and Allende’s visions for revolution. This account tells the story of the strike and takeover of the Yarur Cotton Mill. The stories told by the various participants exhibits Allende’s determination to play by the rules and to work within the existing frameworks to achieve socialist goals and the workers’ impatience with achieving these goals by governmental means. It furthermore expresses how difficult the workers were to control and how hard it was to deny them the liberación they passionately sought. This source furthermore contributes to the theory that hypermoblization of revolutionary forces destabilized the democratic revolutionary effort by the Allende administration.

Saenz, Carmen. “Women Lead the Opposition to Allende: Interview with Carmen Saenz.” By Lisa Baldez and Margaret Power, 1998. Translated by Ryan Judge. In The Chile Reader: History, Culture, Politics. Edited by Elizabeth Quay Hutchinson, Thomas Miller Klublock, and Nara B. Milanich, 406-09. Durham, NC: Duke University Press Books, 2013. Accessed November 1, 2015. ProQuest ebrary.

This is an interview with a Chilean woman who lead a conservative feminist group (Poder Feminino) during the Allende years describing the events of the women’s “March of the Empty Pots” (December 1971). She expresses that she supported the military coup and neo-fascist group called Patría y Libertad (Fatherland and Liberty) which was strongly opposed to the Allende government. According to the footnotes of the provider of the source, she misrepresents facts about the economy that she says caused her disdain for the president. She claims that for her it was a matter of fixing the economy that the introduction of socialism had broken. She cites unbelievable inflation, yet at the time of the protest, inflation had not yet begun to seriously affect the economy.

Allende Gossens, Salvador. “Las Últimas Palabras de Salvador Allende.” Radio broadcast, September 11, 1973. Translated by Trevor Martenson. In The Chile Reader: History, Culture, Politics. Edited by Elizabeth Quay Hutchinson, Thomas Miller Klublock, and Nara B. Milanich, 406-09. Durham, NC: Duke University Press Books, 2013. Accessed November 1, 2015. ProQuest ebrary.

When the military attacked the presidential palace, Salvador Allende gave a final speech broadcasted over the radio just before his death. In this speech Allende addresses the people of Chile, expressing his gratitude for the loyalty of the people and his dismay at the betrayal by the military of Chileans everywhere. An audio recording of the speech with translated subtitles can be found below.

“Salvador Allende’s Last Speech with English Subtitles.” Video file, 6:21. Youtube.com. Posted by Argentina Independent, September 11, 2013. Accessed December 3, 2015. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=HC8UirZLCZQ.

k

COMPANERO PRESIDENTE-

Debray, Régis and Salvador Allende Gossens. The Chilean Revolution: Conversations with Allende. Translated by Ben Brewster, Peter Belgan, Jean Franco, and Alison MacEwan. New York, NY: Pantheon Books, 1972.

Debray, a journalist and academic who fought alongside Che Guevara in Bolivia before his death, writes a glowing assessment of the Allende regime in Chile in a long introduction to two interviews with Allende on the first year of his presidency. Although the author’s bias is apparent, Allende’s interview offers valuable insight into his views on two critical issues: his allegiance to international communism and the relationship of the people to the revolution. In the interview, Allende criticizes international communism. He says that he founded the Chilean Socialist party because the people needed a country founded on Marxist ideas, but with a “broader outlook” that would be independent, designed to meet Chile’s needs and not follow the prescriptions of international organizers, like the Soviet Union and Cuba (62). Allende also addresses the issue of the tension between the democratic revolution from above working within Chile’s existing institutions and the disorganized but impassioned peoples’ revolution from below. He implores the people to organize through existing associations, such as “the Parties, the trade associations, the people’s organizations,” (95).

Allende Gossens, Salvador. “Speech to the United Nations.” Speech presented at United Nations General Assembly, New York, NY, December 4, 1972. Marxists Internet Archive. Accessed November 20, 2015. https://www.marxists.org/archive/allende/1972/december/04.htm.

In this speech before the UN, Allende explains the democratic revolution taking place in his country and the economic pressures from abroad that are causing it harm. Chile is engaged in a, “battle to install social freedoms and economic democracy through full exercise of political freedoms,” he says, but revolutionary Chile is, “the victim of grave aggression,” from abroad. Alluding to the United States, Allende claims that “imperialists” attack Chile through a subtle economic blockade that is highly damaging to Chile’s exercise of sovereignty. This blockade consists of a international lowering of copper prices to retaliate against Chile for nationalizing its copper industry, a credit blockade, inability to purchase needed U.S. machinery, and the halting of economic aid much needed and previously received. The blockade is a “financial stranglehold of a brutal nature,” that is causing great suffering and strife in an already poor nation. Allende also discusses the nationalization of foreign owned corporations, characterizing this as the right of Chile to its own resources, an historic wrong being righted with respect for international law.

U.S. PERSPECTIVES-

Nixon and Kissinger in Austria, 1972.

Unknown source, accessed from stripes.com.

k

Kissinger, Henry A. “Chile: The Fall of Salvador Allende.” In Years of Upheaval, 374-413. Boston, MA: Little, Brown and Company, 1982. Print.

In a chapter in his memoir, Years of Upheaval, former Secretary of State Henry Kissinger addresses the question of the level to which the United States was involved in the counterrevolution that brought down Allende’s government in 1973. Despite evidence to the contrary, he asserts that, “our government had nothing to do with his overthrow and no involvement with the plotters,” of the military coup (374). U.S. involvement was limited to supporting groups advocating democracy, he says. According to Kissinger’s account, “The record leaves no doubt that Chile was not a major preoccupation of the American government after Allende was installed as president,” which contradicts the memo he wrote on Nov. 5, 1970, also included in this guided history (374). He denies the existence of an “invisible blockade” and economic warfare by the Nixon administration against Chile. Kissinger further suggests that Salvador Allende was his own undoing in that he created political instability through radical socialism that he himself could not control. Although Allende was democratically elected and popularly supported, Kissinger associates Allende’s Chile with Mao’s China and the Soviet Union, claiming that Allende sought the eradication of political plurality and democracy in Chile.

Davis, Nathaniel. The Last Two Years of Salvador Allende. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1985. Print.

Nathaniel Davis, author of this historical memoir and U.S. diplomat to Chile during the fall of Allende’s revolution, gives a balanced account of the events that occurred in Chile during the last two years of the revolution. In his work, he neither lionizes nor demonizes Allende, Nixon, Kissinger, or any of the actors in the fall of the Chilean revolution. He gives an inside perspective on the events and conflicts that precipitated the fall of Allende’s democratic revolution and rise of counterrevolutionary forces, such as the mine and transportation strikes, rise of the Chilean military, street protests, and economic crisis. He emphasizes that historians studying Chile’s revolution must not overestimate the role the U.S. played in the counterrevolution; while the U.S. covertly attacked Allende’s government in no small way, forces against Allende had the power to undermine and overthrow him regardless of American influences.

CONTEMPORARY COMMENTATORS-

Medhurst, Kenneth, ed. Allende’s Chile. By Joan E. Garcés, J. Biehl Del Rio, Gonzalo Fernández, H. Zemelman, Patricio Leon, H. E. Bicheno, Gonzalo Martner, and Luis Quiros Varela. New York, NY: St. Martin’s Press, Inc., 1972.

This work is a collection of essays by Chilean academics commentating on the Allende government during his presidency. The contributing authors represent both supporters and opponents of Allende and Unidad Popular. The collection begins with an assessment of the historical background of Chile, followed by essays on the creation of a welfare state, the politicization of the people, “problems and prospects” of Allende’s economic reform, and the significance of the Chilean revolution to other emerging socialist nations. At the end of the collection, Kenneth Medhurst notes that Chile’s “moment of truth,” has not yet come, saying that the fate of La Vía Chilena, “seems to lie between the Jacobin call to ‘save the revolution, threatened by external and internal enemies’, the prelude to Leninism and the dictatorship of the proletariat; or a constitutional acceptance of the limitations on the power of the government,” (194).

k

Allende accepts the presidential sash, 1970.

Photograph by Sonia Aravena Derpich, reproduced in The Chile Reader.

b

SECONDARY SOURCES

TIMELINE OF EVENTS-

Lawson, Chappell. “Chile Timeline.” MIT Open Courseware. Last modified 2002. Accessed November 14, 2015. http://ocw.mit.edu/courses/political-science/17-508-the-rise-and-fall-of-democracy-regime-change-spring-2002/study-materials/chile_timeline.pdf.

This source provides a helpful timeline of the events of the revolution and counterrevolution in Chile from 1970-1973. It is a useful historical resource giving several important dates in the revolutionary period.

h

The Chilean military attacks La Moneda.

Photograph by Enrique Aracena, The Associated Press, accessed from The Chile Reader.

h

GUZMAN DOCUMENTARIES-

Guzman’s documentaries cast the coup as a counterrevolution by the bourgeoisie in Chile. I have included only the first two parts of The Battle of Chile because these focus more on the Allende years and the fall of the regime while the third part focuses more on the Pinochet dictatorship. I have also included Salvador Allende (2004) because this film covers the election of Salvador Allende and exhibits his and the United States’ ambitions for Chile in those years. The Battle for Chile shows how Allende’s opposition worked against his presidency through strikes and attacks on the legitimacy of his administration and their failure during the midterm election of 1973 to stop the revolution’s momentum. The films focus primarily on Chile’s bourgeoisie as the main source of opposition to the revolution, but also acknowledges the external actors at play, such as the C.I.A. While the films do capture the role of fascist groups such as the Patria y Libertad (Fatherland and Liberty), it discounts other popular counterrevolutionary movements in Chile, such as Poder Feminino (Feminine Power).

Guzmán, Patricio, dir. The Battle of Chile: The Insurrection of the Bourgeoisie (Part One). Icarus Films, 1975. Accessed November 19, 2015. Youtube.com. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=b5GeEzBKGsQ.

Guzmán, Patricio, dir. The Battle of Chile: The Coup d’état (Part Two). Icarus Films, 1976. Accessed November 19, 2015. Youtube.com. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qTCVGdq7BAo.

Guzmán, Patricio, dir. Salvador Allende. Icarus Films, 2004.

PRINT SOURCES-

Falcoff, Mark. Modern Chile, 1970-1989: A Critical History. New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction Publishers, 1989. Print.

In this book, historian Mark Falcoff analyzes the story of the Chilean revolution in the grander context of modern Chilean history. He asserts that rather than a revolutionary Marxist ascension to power accomplished democratically, Allende’s election was, “nothing more than the culmination of long-standing trends in post-war Chilean political history,” (251). He analyzes these political trends and suggests that Allende’s election (in which he captured only a little over a third of the popular vote) did not reflect the true sentiments of the electorate. While there was need for reform and restructuring of the government and income distribution, La Vía Chilena al Socialismo was not what the people wanted (20). Falcoff furthermore suggests that a military coup was not what the United States wanted. In his interpretation of the Church Report (a Congressional investigation of U.S. intervention in Chile), he claims that the U.S. did not attempt to create conditions for a junta, but rather, “a rematch, in which the political forces of the country would more nearly reflect its actual currents of opinion,” (11). The example of U.S. attempts at intervention are thus more an example of the limits of international hegemony rather than the strength of a foreign power’s influence.

Harmer, Tanya. Allende’s Chile and the Inter-American Cold War. Chapel Hill, NC: The University of North Carolina Press, 2011. Print.

The author of this book suggests that Chile was but one important episode in a larger Cold War between the U.S. and Latin America. The struggle of Chile for democratic socialist revolution under the shadow of U.S. hegemony and interventionism in the Western Hemisphere epitomized the struggle of Latin America in general during the Cold War. Although Harmer acknowledges that the failure of democratic revolution in Chile was not solely due to foreign intervention, “this book deals with the impact external actors had on Chilean domestic policies,” (5). Nixon and Kissinger’s goals for intervention were not driven by economic or corporate interests, but more by U.S. political interests. Détente did not exist in the Western Hemisphere and Allende failed to understand the extent to which the United States was willing to involve itself in Chile. Harmer suggests that the opposition of Allende and his supporters to U.S. involvement in American affairs was more disturbing to the Nixon administration than nationalizations or any possible Soviet encroachments in the Western Hemisphere.

Kaufman, Edy. Crisis in Allende’s Chile: New Perspectives. New York, NY: Praeger Publishers, 1988. Print.

In Edy Kaufman’s work on the Chilean revolution and its downfall, he suggests that the failure of the Allende regime was due less to the extremists of the political right and left, and more to the failure of political compromise. His analysis of internal factors causing the violent end of the revolution suggests that responsibility falls more to the political moderates in the country who were unsuccessful in asserting a middle ground among the political clamor. He furthermore claims that the influence of international powers, particularly in this case, the U.S., the Soviet Union, and Cuba, was no less important for the Chilean situation, it being a “Third World” nation, dependent on international aid and trade of its few main exports (39). Thus in this book, the author seeks to bring focus to both the internal and external factors at play, rather than emphasize one more than the other as different observers have done.

Sigmund, Paul E. The Overthrow of Allende and the Politics of Chile, 1964-1976. Pittsburgh, PA: The University of Pittsburgh Press, 1977. Print.

In this book, political scholar Paul E. Sigmund analyzes Allende, his predecessor, and his successor. It is a balanced account that offers, by its author’s own admission, no single explanation for the failure of the democratic revolution and subsequent coup. Although the author analyzes the external pressures that caused strife in Chile during the revolutionary years, he also acknowledges the serious impact of Allende’s polarizing policies and the destabilizing effect of their too rapid application to Chilean society. The balanced nature of the author’s study of the revolution and counterrevolution is best captured by his own words:

“Allende was neither an innocent social-democrat overthrown by fascist thugs and the CIA, nor a Marxist revolutionary who manipulated Chile’s democratic institutions in order to set the stage for a violent Communist seizure of power. Rather, he was a skilled parliamentarian politician committed to aiding the poor and under-privileged, who could never abandon his romantic admiration for those, like Castro and Guevara, who had waged a successful armed revolution,” (xiii).

Vicuña, Francisco Orrego, ed. Chile: The Balanced View. Santiago, Chile: University of Chile Institute of International Studies, 1975. Print.

This source is a collection of articles, essays, and primary sources assessing the revolution, Allende’s government, and the military takeover in Chile. The contributors include historians, academics, political commentators, and government officials. The collection is broken into four parts: political history, U.S. economic interventions, Allende’s economic goals, and responses from U.S. government officials on intervention. Paul Sigmund’s article giving a brief history of events and an assessment of the causes of counterrevolutionary movements in Chile is especially useful for its analysis of what he calls “deliberate class polarization” by the Allende regime (37). Francisco Orrego Vicuña also gives a good analysis of the problems with the nationalization of copper.

HYPERMOBILIZATION-

Landsberger, Henry A., and Tim McDaniel. “Hypermobilization in Chile, 1970-1973.” World Politics 28, no. 4 (July 1976): 502-41. Accessed December 2, 2015. doi:10.2307/2010065.

Henry Landsberger and Tim McDaniel, authors of this article, theorize that at the time of revolution, the disorganized working class in Chile was too quickly mobilized, thereby undermining the democratic socialist revolution attempted by Allende. According to the authors, hypermobilization occurs when a social group is mobilized by political forces and it seeks to fulfill all of its needs as quickly as possible, but cannot because of the lack of resources, causing conflict. These conflicts occurred between Allende and the working class of Chile, who saw the democratic processes as not working fast enough to suit their needs. Furthermore, although the Chilean working class was politically “mature” relative to other underdeveloped nations, the authors suggest that the working class in Chile was not united behind any single set of ideologies, let alone a revolutionary ideology, as approximately one quarter of unions were lead by Christian Democrat supporters and less than half by Marxists (510). Landsberger and McDaniel conclude that, “political change requires some degree of control over mobilization,” as it is a double edged sword for those leading the people in a revolution (506).

Women during the March of the Empty Pots.

Photograph by Peter Winn, reproduced in The Chile Reader.

j

ROLE OF WOMEN-

Power, Margaret MacDonald. “Right-wing women and Chilean politics: 1964-1973” Doctoral thesis, University of Illinois at Chicago, 1997. UMI Dissertations Publishing 1997. Accessed November 14, 2015. ProQuest Dissertations & Theses Global.

The author of this dissertation, Margaret Power, analyzes the role of conservative women in 1960s Chile, in opposing the Allende government, and in the Chilean counterrevolution in 1973. Power answers the questions of how and why conservative women’s groups came to be radicalized during this time. She suggests that Chile’s conservative right succeeded in mobilizing the nation’s women by reinforcing, “traditional ideas about gender, that conflated womanhood with motherhood, and [used] these concepts [as] key to the building of this movement,” (xiv). Reinforcement of these traditional notions coupled with media campaigns associating communism with the destruction of morals and society convinced Chile’s women that the survival of the family was contingent on the survival of capitalism. The result was violent protests by women’s groups, demanding Allende’s removal by any means.