Created by Ian Blau in the Fall semester 2012 at Boston University.

“The first film I decided to make, I decided it will be folklore, tradition, music, singing and humor. Because when I came to Poland, I found all these elements among the [Yiddish-speaking, Jewish] people. “

– Joseph Green (Director/Producer/Writer)

INTRODUCTION

An industry of firsts, Yiddish cinema began in early Yiddish theater in the Russia, which in turn was rooted in Yiddish literature. This created an inherently Jewish industry that encapsulated international Yiddish culture before its ultimate demise in the middle twentieth century. Produced across the globe under ranging political and occupational circumstances, Yiddish films uniformly struggled to find proper financing and distribution. There’s also a limited number of primary sources as many of the genre’s most influential members did not speak extensive English or have passed away without providing widely available interviews or writings. Additionally, many of Yiddish pictures have been lost and only recently resurrected by the National Center for Jewish Film at Brandeis University. As a result, there is not a finely detailed or extensive history of the industry. But, the books Laughter through Tears: The Yiddish Cinema by Judith Goldberg and Visions, Images, and Dreams: Yiddish Film Past and Present by Eric Goldman, along with the work done by the YIVO Institution and the National Center for Jewish Film have helped provide a general, informative background of the genre.

Adapting with the newest forms of technology and changing political and societal beliefs in the early twentieth century, films in Yiddish were produced and distributed in Poland, the Russian Empire/Soviet Union, and, most prominently, the United States. Within the United States, Henry Lynn, Edgar Ulmer (associated with Collective Film Producers) and Joseph Seiden (founder of Judea Pictures Corporation) sculpted the Yiddish film industry for many recent immigrants. In Poland, Joseph Green (a Polish, former Yiddish theater and American Yiddish film actor) started touring films to large audiences; this led to the production of his own Yiddish films. Russia began to make the first “Yiddish” silent films, in 1910, under Soloman Mikhoels and his Moscow State Jewish Theater. Almost all later Soviet Yiddish films relied on the Communist’s film company, VUFKU Films in Ukraine, for production. Other than the only non-VUFKU produced Yiddish Soviet film, Noson Beker Fort Ahey, all “Yiddish” Soviet films were silent. Each region provided a unique outlook and style to Yiddish film. The genre also acted as a parallel for Yiddish culture and Jewish history. After World War Two, when Yiddish cinema began to decline, Joseph Green stated that he stopped making Yiddish films because, “Six million potential moviegoers are missing, and they are the most important audiences for Yiddish films.” The genre never looked for mainstream success or acceptance, rather it tried to create a comforting and artistic medium for Yiddish-speaking Jews around the world.

The region represented by each annotated source is noted in brackets.

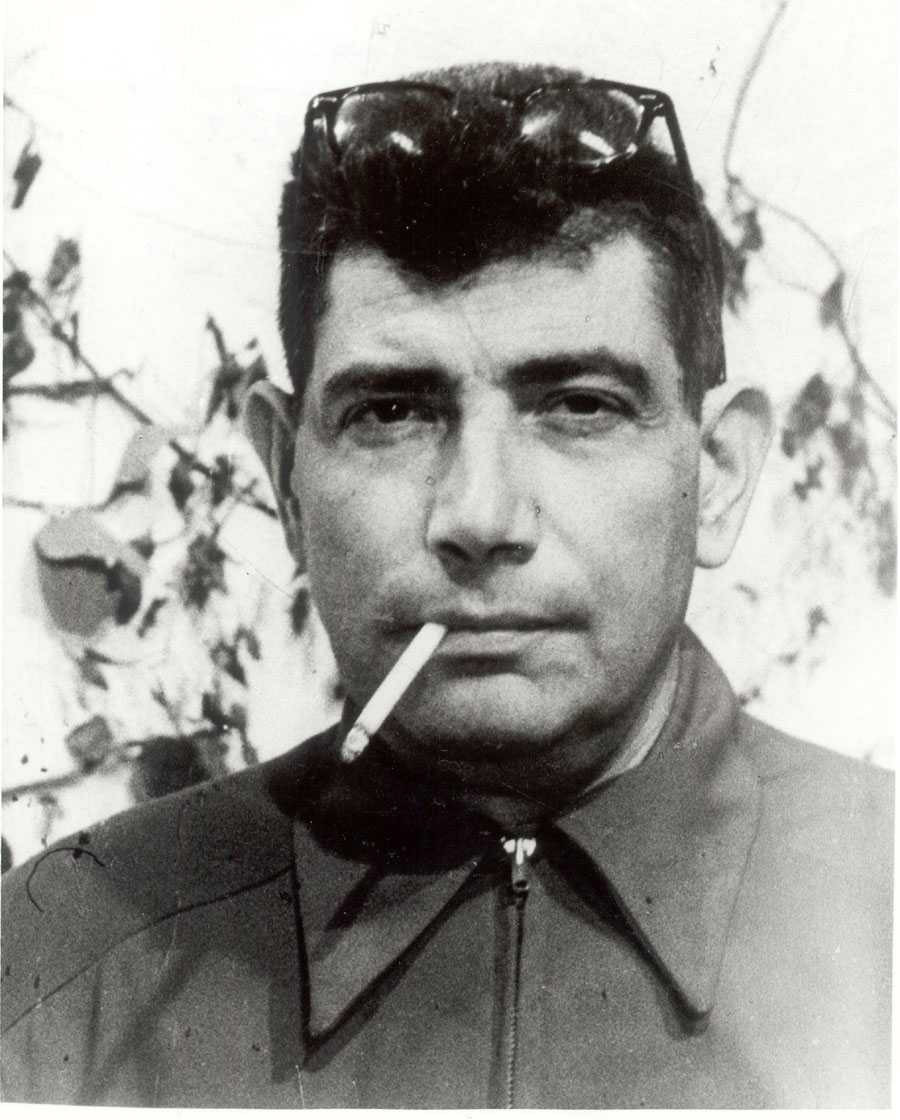

Edgar G. Ulmer (US) (Director) || Joseph Green (Poland) (Director/Producer)

GENERAL OVERVIEW

Goldberg, Judith. Laughter through Tears: The Yiddish Cinema. New Jersey: Associated University, 1983.

Judith Goldberg’s Laughter through Tears: The Yiddish Cinema provides a well-rounded history of Yiddish cinema’s roots in theater, its major figures and companies. It also provides an in-depth look into Poland’s Yiddish cinema industry. Goldberg creates detailed accounts of the genre while keeping with an easy to process writing style. [USA and Poland]

Goldman, Eric. Visions, Images, and Dreams: Yiddish Film Past and Present. Michigan: UMI Research, 1983.

Eric Goldman’s Visions, Images, and Dreams: Yiddish Film Past and Present creates another detailed history of the industry and genre. Unlike Goldberg’s book, Goldman focuses on each film individually, explaining the context and history that went into each production. Also, unlike Laughter, Goldman writes extensively about the Soviet Union’s turbulent relationship with the Yiddish cinema. [USA and Soviet Union]

Hoberman, James. Bridge of Light: Yiddish Cinema Between Two Worlds. Philadelphia: Temple, 1995.

James Hoberman’s textbook, Bridge of Light: Yiddish Cinema Between Two Worlds guides the reader through the history of Yiddish film based on time period. The detail of resources and information in the book from early filmed stage productions to 1980s revivalist Yiddish cinema is unmatched. Hoberman hits upon every major producing nation of Yiddish film, as well as it’s influential directors, writers and actors. The only complaint with the book is that it is organized by time and not by nation, making it difficult to quickly find a biography on one person or nation, rather the reader must search throughout the entire text to find specific information. [USA, Poland and Soviet Union]

A shot from the Yiddish classic, The Dyubbuk. Directed by Michal Waszynski.

(Watch a clip by clicking here.)

DIRECT QUOTATION SOURCES

Blumenthal, Ralph. “Joseph Green, 96, Creator Of Yiddish Film’s Heyday.” The New York Times, June 22, 1996, sec. Arts.

Blumenthal’s obituary on the legendary Polish-born, Yiddish director and producer creates a clear history of Joseph Green. Between his personal life and his occupational life, the article includes quotes from Green discussing these topics. Overall, the article provides context for Green’s work as well as information on his later life and his reasoning for leaving the Yiddish film business. [Poland]

The Yiddish Cinema. DVD. Directed by Rick Pontius. Boston: National Center for Jewish Film, 1991.

Directed by Rick Pontius, The Yiddish Cinema explains the early history of Yiddish film from its roots in Yiddish theater and literature in the Soviet Union. Moving from the Soviet Union to Poland and the United States, the film includes interviews with Solomon Mikhoelz’s children, Joseph Green and many more. The movie ends in the United States with a history of Joseph Seidan and Edgar Ulmer’s work. Along with the interviews, the film is broken up by clips of classic Yiddish films from the different interviewees, placing their words into context of the clips. The interviews with family, directors and actors of Yiddish cinema help provide a strong oral history behind some of the most influential members of the Yiddish film industry. [Soviet Union, Poland, USA]

SPECIFIC PEOPLE/FILMS INFORMATION

Hoberman, James, ed. The YIVO Encyclopedia of Jews in Eastern Europe. New York: YIVO Institute, s.v. “Cinema.”

Hoberman’s entry into the YIVO Encyclopedia provides details about Jewish and Yiddish cinema in Eastern Europe, specifically the Soviet Union. One unique aspect of Hoberman’s piece are his biographies of influential Jewish and Yiddish film personalities. [USA, Poland, Soviet Union]

Schechter, Joel. “Yiddish King Lear on the Relief Roll.” The Jewish Daily Forward, sec. Theater, December 08, 2008. (accessed November 1, 2012).

Schechter’s article focuses on the stage production of King Lear’s movement to film. The article provides a detailed history of the production and the key figures that went into creating the filmed adaptation of the play. In particular, Schechter focuses on the roll that the United States’ government, especially the WPA, played in Yiddish theater and arts. [USA]

Sela, Maya. “Tongue-tied on the page.” Haaretz, April 14, 2010. (accessed November 1, 2012).

Sela’s review of David Markish’s book on Isaac Babel helps create an interesting picture of the Yiddish writer. Markish and Sela speak about Babel’s influence on Yiddish art and Babel’s personal history. The book review added details about Babel and how this influenced his larger role in Yiddish cinema. [Soviet Union]

Cast of The Yiddish King Lear (Joseph Seiden)

(Watch a clip of the Moscow Jewish State Theater performing The Yiddish King Lear by clicking here.)

GENERAL GENRE INFORMATION

Chantal, Michel. Montclair State University, “The Yiddish Cinema.” Accessed November 1, 2012.

Michel Chantal’s database, “The Yiddish Cinema”, includes articles and dissertations from the Montclair State University professor. Although the base of the website is in French, the academic format and translations of her work allow the website to be a vital tool in finding information and researching Yiddish cinema. [USA, Soviet Union and Poland]

Chantel, Michel. “Yiddish Cinema: Cinema Identity or Mirror Eyes of Others?” (PhD diss., Université Paul Valéry, 1998).

One particular piece on Michel Chantal’s “yiddishcinema.net” website is her PhD dissertation. Although in French, the work explains the motives of Yiddish cinema and the idea of finding identity through the genre. Michel goes into detail about how specific films and specific influential figures of Yiddish cinema helped sculpt the genre into an international image of Jewish cultural life. [USA, Soviet Union and Poland]