A Research Guide

by Cristina Gallotto

Introduction

This research guide covers primary and secondary sources concerning religious symbolism in public schools in The United States and France. From landmark cases and excerpts from state constitutions, to a diverse set of news articles and museum artifacts, this guide categorizes and annotates an in-depth, yet concise resource exhibit demonstrating the role of religious symbolism in public education. The guide then turns to scholarly secondary sources that analyze this raw material. Together, this collection of sources provides a starting point for a comparative analysis of French and American secularism in public schools.

France and The United States have particularly strong penchants for religious liberty by law, and both have rich legal histories portraying how they have implemented those laws in public schools. This research guide demonstrates that Americans are mostly concerned about freedom of religion; the French freedom from religion. Despite similar frameworks for secularism and laicite, or the absence of government involvement in religious affairs, France and the USA operate on two dramatically different ideas of religious freedom. A comparative study of the two makes for an interesting dialog about the meaning of religious symbolism in public schools in secular liberal democracies.

Why does “secular” take on two different meanings in two similarly democratized societies? Why have citizens of both countries taken this issue to high courts time and time again? What do the French and American people believe is at stake here? And why is the classroom so special?

Reading these documents should show you how religious symbolism drives national debate about secularism in public schools. It should help clarify how religious and cultural biases continue to shape the conversation today. And most importantly, it should inspire within you a genuine introspection regarding whether your own beliefs about church and state comport with that of your country.

A topic with a tumultuous history, religious symbolism in public schools continues to be a deeply divisive topic for France and The United States, as these documents show.

France

Primary Sources

The Law

Religious freedom is a cornerstone of French law written explicitly in the French Constitution. France has had five republicans. The first Constitution in 1791wrote one thing on religious practice, that:

Constitution of the French Republic (1791):

“[T]hose who, born in a foreign country and descended in any degree whatsoever from a French man or a French woman expatriated on account of religion, may come to live in France and take the civic oath.”

(http://www.historywiz.com/primarysources/const1791text.html)

It was not until 1946 that the French Constitution explicitly used the word “laicite” to describe the separation of church and state. (http://www.conseil-constitutionnel.fr/conseil-constitutionnel/francais/la-constitution/les-constitutions-de-la-france/constitution-de-1946-ive-republique.5109.html)

Since then, it has come to identify France as a secular republic. Below is an excerpt from the most recent Constitution, where there remains an explicit explanation of laicite:

Constitution of the French Republic (4 October 1958), Article 1 (French & English):

La France est une République indivisible, laïque, démocratique et sociale. Elle assure l’égalité devant la loi de tous les citoyens sans distinction d’origine, de race ou de religion. Elle respecte toutes les croyances. Son organisation est décentralisée.

La loi favorise l’égal accès des femmes et des hommes aux mandats électoraux et fonctions électives, ainsi qu’aux responsabilités professionnelles et sociales.France shall be an indivisible, secular, democratic and social Republic. It shall ensure the equality of all citizens before the law, without distinction of origin, race or religion. It shall respect all beliefs. It shall be organised on a decentralised basis.

Statutes shall promote equal access by women and men to elective offices and posts as well as to professional and social positions.

Additionally, France is part of the European Convention on Human Rights, which asserts:

Article 9 – Freedom of thought, conscience and religion:

1. Everyone has the right to freedom of thought, conscience and religion; this right includes freedom to change his religion or belief and freedom, either alone or in community with others and in public or private, to manifest his religion or belief, in worship, teaching, practice and observance.

2. Freedom to manifest one’s religion or beliefs shall be subject only to such limitations as are prescribed by law and are necessary in a democratic society in the interests of public safety, for the protection of public order, health or morals, or for the protection of the rights and freedoms of others.

(European Convention on Human Rights – European Court of Human …)

In 1989, Conseil d’État (Council of State), France’s highest administrative tribunal, sought measures to resolve the growing controversy of religious symbolism in public schools. This came after “The Headscarf Affairs”, a situation in Creil, Paris where three young female students refused to remove their headscarves in the classroom. Following a substantial amount of media attention and widespread discomfort with the issue, the French government detailed their opinion:

It results from the above that, in teaching establishments, the wearing by students of symbols by which they intend to manifest their religious affiliation is not by itself incompatible with the principle of laïcité, as it constitutes the free exercise of freedom of expression and of manifestation of religious creeds, but that this freedom should not allow students to sport signs of religious affiliation that, due to their nature, or the conditions in which they are worn individually or collectively, or due to their ostentatious and provocative character, would constitute an act of pressure, provocation, proselytism or propaganda, or would harm the dignity or the freedom of the student or other members of the educative community, or would compromise their health or safety, or would perturb the educational activities or the education role of the teaching personnel, or would trouble public order in the establishment or the normal functioning of the public service. (Official website of Le Conseil d’Etat)

(http://www.conseil-etat.fr/content/download/635/1933/version/1/file/346893.pdf)

Le Conseil d’Etat wrote not that these veils were a violation of secularism itself, but that they compromise, essentially, elements of public space that together make for a secular space.

Through the 1990s there were a series of similar situations that resulted in tightening of regulations by Le Conseil against religious symbolism in the classroom, mostly aimed at curbing the wearing of Islamic veils in the classroom. For example:

On 14 March 1994, the Conseil ruled that a school regulation prohibiting any headgear was excessive.

On 10 March 1995, the Conseil upheld the expelling of three students for wearing headgear in a physical education class, and cited the 1989 ruling to indict these individuals.

Through the late 1980s and into the beginning of the 21st century, French educators, legislators, and citizens felt these laws were vague and needed to be clarified. In 2003, French President Jacques Chirac moved to enact a law.

By 2004, the French government had enacted a law that band on religious symbolism in public classrooms (http://www.stetson.edu/law/conferences/highered/archive/media/French%20Education%20Code%20Title%20IV.pdf):

Article L141 -5-1 (French & English)

Created by Act No. 2004-228 of 15 March 2004 – s. 1 Official Journal of 17 March 2004 in force on 1 September 2004

Dans les écoles, les collèges et les lycées publics, le port de signes ou tenues par lesquels les élèves manifestent ostensiblement une appartenance religieuse est interdit. Le règlement intérieur rappelle que la mise en oeuvre d’une procédure disciplinaire est précédée d’un dialogue avec l’élève.

In schools, colleges and public high schools, the wearing of signs or clothes by which pupils overtly manifest a religious affiliation is prohibited.

The rules shall state that the implementation of disciplinary proceedings shall be preceded by a dialogue with the student.

Notable subtext of this 2004 law helps us understand it in greater depth:

Ils contribuent à favoriser la mixité et l’égalité entre les hommes et les femmes, notamment en matière d’orientation.(They help foster gender equality and gender equality, particularly in terms of guidance.)

Le service public de l’éducation fait acquérir à tous les élèves le respect de l’égale dignité des êtres humains, de la liberté de conscience et de la laïcité. (The public service of education gives all pupils respect for the equal dignity of human beings, freedom of conscience and secularism)

L’école garantit à tous les élèves l’apprentissage et la maîtrise de la langue française. (The school guarantees to all students the learning and mastery of the French language.)

More here from the French Ministry of education on their pledge to secularism: (http://eduscol.education.fr/cid76044/the-secularism-charter-la-charte-de-la-laicite.html)

As a result of this 2004 law, the Ministry of Education reported that only 12 students showed up with distinctive religious signs in the first week of classes, compared to 639 in the preceding year. Le Conseil d’Etat released this statement in favor of the 2004 law: http://www.conseil-etat.fr/Decisions-Avis-Publications/Etudes-Publications/Rapports-Etudes/Un-siecle-de-laicite-Rapport-public-2004

Since the passing of that law in 2004, a number of cases have gone to high French courts to petition the law’s legitimacy. Those making the claims say that French laicite in public schools strips them of their European right to religious freedom in public space, which is guaranteed to them by Article 9.

Court Cases Regarding Secularism in Public Schools

(All cases can be read about in greater depth here: http://www.echr.coe.int/documents/fs_religious_symbols_eng.pdf)

Aktas v. France, Bayrak v. France, Gamaleddyn v. France, Ghazal v. France, J. Singh v. France and R. Singh v. France (June 30, 2009)

Allegation: Six students were expelled for wearing overtly religious symbols. They were enrolled in various state schools for the year 2004-2005. These students were denied access to a classroom on the first day of school for wearing Islamic headscarves or male Sikh “keski”s. After an extended period of dialog with families, the schools expelled them for failure to comply with the Education Code. The six students relied on Article 9 of the Convention to assert their right to religious freedoms.

Result: The court declared the six applicants “manifestly ill-founded”, holding in particular that the interference with pupils’ freedom to manifest their religion was prescribed by law and pursued the legitimate aim of protecting the rights and freedoms of others and of public order. This finding emphasized the State’s role as a protectorate of religious freedoms.

Dogru v. France and Kervanci v. France (December 4, 2008)

Allegation: The applicants, both Muslims, were expelled from school in 1998-1999 for refusing to remove their headscarves in physical education classes. The students believed the expulsion came from religious conviction, not legitimate disruption of classroom activity.

Result: Court upheld their expulsion, citing their attire as incompatible with sports classes for reasons of health and safety. The court also cited their refusal to comply with the rules on school premises.

(ECHR)

In light of these cases, the legitimacy of this law in concordance with ECHR law came into question. In 2014, the EHRC declared by a majority that “French ban on the wearing in public of clothing designed to conceal one’s face does not breach the Convention”:

“The Court emphasised that respect for the conditions of “living together” was a legitimate aim… there had been no violation of Article 8 (right to respect for private and family life) of the European Convention on Human Rights, and no violation of Article 9 (right to respect for freedom of thought, conscience and religion)”

The landmark French cases were not one of a kind. Rather, they followed a landmark case that set precedents for religious symbolism in public schools within the European Court of Human Rights.

The landmark case that set the precedent in Europe for the display of religious symbols in State-school classrooms is Lautsi and Other v. Italy (2011)

Allegation: An applicant claimed the crucifixes that hung on the walls of all of the classrooms in her children’s public school was contrary to the secular ideals she hoped to raise her children with. The applicant spoke with school governors with her husband who requested the removal of the crucifixes. The school governors decided to keep the symbols up. Following further complaints to school administrators, the applicant took her complaint to the Court, claiming the crucifixes violated Article 9 and Article 2 of the European Convention on Human Rights. Article 9 guarantees freedom of thought, conscience, and religion. Article 2 guarantees a right to education.

Result: The European Court of Human Right’s Grand Court held that there was no violation of Article 2 (right to education), and that no issue arose under Article 9 either. It was found, rather, that this was a majority cultural expression, not a religious one. The court said there was nothing to suggest authorities were in any way intolerant of non-Christians. The court did remind the applicant her right as a parent to guide her child down the philosophical convictions of her own will.

Debate over these cases has shaken the French and international community alike, and the media outlets in France and the United States have covered religious symbolism in schools extensively:

Journalistic Sources

French Covering French Cases

In an article written in the French national publication Le Figaro, Journalist Mathilde Siraud wrote of the violent reaction of a law professor of a veiled student in his university classroom. Titled, “La violente réaction d’un professeur de l’école du barreau devant une étudiante voilée”, the article highlights how emotionally incendiary this topic has come to be. Private universities are exempt from the ban on religious symbolism in classrooms. (http://etudiant.lefigaro.fr/les-news/actu/detail/article/la-violente-reaction-d-un-professeur-de-l-ecole-du-barreau-devant-une-etudiante-voilee-10605/)

Le Figaro’s television outlet, FigaroTV, aired a piece with Tarew Oubrou, an Imam of the mosque of Bordeaux, France in April of 2016. Oubrou does not understand how a scarf in a university setting disturbs public order. This source displays how the minority Muslim voice is portrayed in mainstream French media as recent as this year, and it shows the continuation of this debate that began over a decade ago. (http://video.lefigaro.fr/figaro/video/tareq-oubrou-je-ne-vois-pas-en-quoi-un-foulard-a-l-universite-trouble-l-ordre-public/4844465667001/)

US Covering French Cases

New York Times, “French Assembly Votes to Ban Religious Symbols in Schools” by Elaine Sciolino (February 11, 2004): The American paper of record reports that the 2004 French law underscores broad public support for French secular ideal, but that it will likely worsen relations between French and their French Muslim counterparts. The NYT also writes that the law bars religious dress in physical education classes, and more. This is an objective piece from American point of view. The article writes,

“The draft law bans ”ostensibly” religious signs, which have been defined by President Jacques Chirac and a government advisory commission as Islamic head scarves, Christian crosses that are too large in size and Jewish skullcaps. Sikh turbans are also likely to be included…Schools, it said, are ”the best tool for planting the roots of the republican idea.”

New York Times, “French Ban on Veils Goes Into Force” by Steven Erlanger: This piece writes of this law as radical piece of legislation. Erlanger highlights the tension within the police, the French people, Muslim women who feel victimized. It humanizes and protagonizes the Muslim voice above all.

(http://www.nytimes.com/2011/04/12/world/europe/12france.html)

Other Diverse Artifacts / Exhibits

Le Bibliothèque nationale de France presents a virtual exhibition of this laicite in public schools. It explains the French perspective throughout history through art and ideas from notable thinkers. This article gives a French perspective on basic questions and uses nationally acclaimed art and modern political cartoons to back up their claims: http://classes.bnf.fr/laicite/

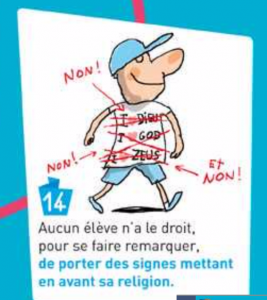

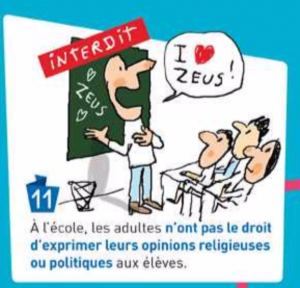

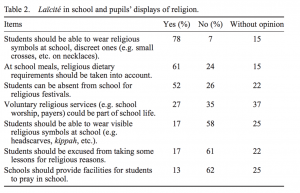

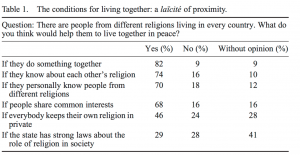

Bérengère Massignon conducted research and compiled it into a virtual exhibit called “Laïcité in practice: the representations of French teenagers, British Journal of Religious Education”. With interviews, polls, and quantitative research, this article sets out how French pupils (grades K-12) conceive of laïcité, both generally and in school. It also explores pupils’ perceptions of the 2004 law banning the wearing of ostentatious religious symbols in state schools and their perceptions of the current arrangements for dealing with pupils’ religiously motivated requests. Some of his most pertinent topics to religious symbolism in public schools in France is included below.

(http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/pdf/10.1080/01416200.2011.543598?needAccess=true)

Secondary Sources

Books

Because critics believe the law against religious symbolism in public schools is an attack on Islam in France, I felt it essential to include literature on why exactly modern day Muslim women dress the way they do.

The books that cover this topic well include:

“The Headscarf Controversy: Secularism and Freedom of Religion” by Elver Hilal: An interdisciplinary study, and in some senses commentary, discussing tolerance of female Muslim dress in various countries, including but not limited to France and the United States.

“The headscarf debates: conflicts of national belonging” by Gökçe Yurdakul and Anna C. Korteweg: A colorful analysis of the contentious meaning behind the headscarf and the undeniable role it plays in shaping national debate and policymaking.

“Why the French Don’t Like Headscarves. Islam, the State and Public Space” by John R. Bowen: A perspective from an American anthropologist in France at the time of the passing of the 2004 law. He observed as this dramatic debate unfolded, and writes about how public life, the media, and the government were consumed with the events that followed.

Scholarly Articles

A number of scholarly articles have done quite well in addressing the same topic in recent years:

“France Upside down over a Headscarf?” by Sophie Body-Gendrot: This article addresses the controversial banning of the headscarf (“hijab”) worn by Muslim girls in French schools, the role of neutrality in public space, and the French perception of Muslim women in France. It considers the religious symbolism in Islamic terms, an opinion less noted in French law. (http://www.jstor.org/stable/20453165?seq=1#page_scan_tab_contents)

“Veiled Meaning: The French Law Banning Religious Symbols in Public Schools” by Justin Vaïsse: This article writes that the USA widely condemns this law. It promotes the freedoms the USA affords to various religious minorities and how American “public schools can be accommodated without violating principles of religious freedom”, but that France’s are not as accepting. *Note that this article is from the typically liberal Washington, D.C. think tank, Brookings Institute. * (https://www.brookings.edu/articles/veiled-meaning-the-french-law-banning-religious-symbols-in-public-schools/)

Other scholarly articles confront this topic in other ways…

“The Great Divide: The Ideological Legacies of the American and French Revolutions” by Kim R. Holmes: Holmes discusses the roots of America’s and France’s differing approach to secularism. America’s freedoms come from negative rights, or guaranteed areas that the government cannot touch. Contrarily, France’s freedoms come from impositions on citizenry, or “necessary conditions [government] must deliver to reach those ideals.” *Note: This article is from the conservative Washington, D.C. think tank, The Heritage Foundation. * (http://www.heritage.org/research/lecture/2014/08/the-great-divide-the-ideological-legacies-of-the-american-and-french-revolutions)

“France: Submission to the National Assembly Information Committee on the full Muslim Veil on National Territory” an article by The Human Rights Watch: A neutral view on the 2004 law that comments from a human rights perspective on Dogru v. France, Kervanci v. France, Mann Singh v. France, Aktas, Bayrak, Gamaleddyn, Ghazal, Jasvir Singh, and Ranjit Singh v. France. (https://www.hrw.org/news/2009/11/20/france-submission-national-assembly-information-committee-full-muslim-veil-national)

“Laïcité in practice: the representations of French teenagers” by Bérengère Massignon: A compilation and scholarly analysis of various interviews with French pupils on their understanding of laïcité in their public classrooms since 2004. (Linked above with numerical charts, and again here: http://www-tandfonline-com.ezproxy.bu.edu/doi/pdf/10.1080/01416200.2011.543598?needAccess=true)

“Religion in France”, An article by Oxford Scholarship: Explains Tocqueville’s role in the question of religion and public education. Incorrigible differences between Catholicism and democratic society, he wrote, sit at the core of lasting issues of the church and the state in regards to public education. (http://www.oxfordscholarship.com/view/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199681150.001.0001/acprof-9780199681150-chapter-8)

USA

Primary Sources

The Law

The First Amendment of the U.S. Constitution guarantees religious freedom as a priority in law

Article [I] (Amendment 1 – Freedom of Expression and Religion): (http://constitution.findlaw.com/amendment1.html)

Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof; or abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press; or the right of people to peaceably assemble, and to petition the Government for a redress of grievances.”

The First Amendment has two provisions concerning religion: The Establishment Clause and the Free Exercise Clause:

The Establishment Clause prohibits the government from “establishing” a public religion.

The Free Exercise Clause protects citizens’ right to practice their religion as they please, so long as the practice does not run afoul of a “public morals” or a “compelling” governmental interest.

(For an easy-to-read version of the Constitution, click here: http://constitutionus.com)

Laws regarding public religion in the United States are clearly delineated by law. In law, and in the classroom in particular, freedom of religion is emphasized. But still, over the course of American history, religious symbolism in public spheres has come into question courts in small districts and all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court itself. Here are some landmark cases that help us identify is gets challenged despite the law.

Court Cases Regarding Secularism in Public Schools

In the progressive legislative era of the 1960’s, a number of Supreme Court cases struck down prayer in public schools:

Engel v. Vitale (1962): New York’s requirement of a state-composed prayer to begin the school day was declared an unconstitutional violation of the Establishment Clause: https://www.oyez.org/cases/1961/468

Abington School District v. Schempp (1963): A Pennsylvania law requiring that each public school day open with Bible reading was struck down as violating the Establishment Clause: https://www.oyez.org/cases/1962/142

Murray v. Curlett (1963): A Maryland law requiring prayer at the beginning of each public school day was declared unconstitutional as a violation of the Establishment Clause. Murray and his mother, professed Atheists challenged the policy for required readings of bible versus: https://www.oyez.org/cases/1962/142

Today, the Lemon Test helps the government decide appropriate cases to rule in favor of protecting religion in the public sphere.

Lemon v. Kurtzman (1971): The Lemon Test, set forth by the 1971 U.S. Supreme Court case Lemon v. Kurtzman, considers three core questions:

- If the primary purpose of the assistance is secular

- If the assistance neither promotes nor inhibits religion

- If there is no excessive entanglement between church and state

(https://www.oyez.org/cases/1970/89)

That precedent is upheld today in cases of the 21st century:

Santa Fe Independent School District, Petitioner v. Jane Doe (2000):

Allegation: A school district in Texas allowed overtly Christian prayer over the intercom system before school football games. A Mormon and Catholic family filed a suit alleging tat this practice violate the Establishment Clause of the First Amendment. While the suit was pending, the school changed their policy. They put it to a vote to decide 1. If “invocations” should be given, and 2. If so, then who should give them? As long as the prayers were “nonsectarian and non-proselytizing”, the District Court deemed their temporary policy to be permissible. The Court of Appeals, though, decided that their new football prayer policy was invalid. Santa Fe School District petitioned for a writ of certiorari, citing football game “invocations” are private speech, and therefore not a violation of the Establishment Clause.

Result: The Santa Fe School District’s policy permitting student-leg, student-initiated prayer at football games does indeed violate the Establishment Clause of the First Amendment. The court held that this speech on school property at school-sponsored events over a public speaker system is characterized as public speech, and that regardless of a personal belief any prayer will be perceived as having the school’s seal of approval, which is a violation of the clause.

Elk Grove Unified School District v. Newdow (2004):

Allegation: A father challenged the constitutionality of requiring public school teachers to lead the Pledge of Allegiance, which has included the phrase “under God” since 1954. Does a public school district policy requiring the imposition of allegiance to a nation “under God” violate the Establishment Clause of the First Amendment?

Result: The Court determined that Mr. Newdow, as a non-custodial parent, did not have standing to bring the case to court and therefore did not answer the constitutional question. The question, though not clearly answered by the U.S. Supreme Court, has been hotly debated ever since.

The media has covered this topic extensively, and there have been some very notable pieces that give color to the ways in which conflicts over religious symbolism in schools affect the American people directly.

Journalistic Sources

US Covering US Cases

The Atlantic, “The Misplaced Fear of Religion in Classrooms” by Melinda D. Anderson: Linda K. Wertheimer, a veteran education writer and editor, and author of Faith Ed: Teaching about Religion in an Age of Intolerance, comments on the friction and sometimes outright confrontation over teaching religion in public schools. The Atlantic published the interview. (http://www.theatlantic.com/education/archive/2015/10/the-misplaced-fear-of-religion-in-classrooms/411094/)

The Christian Times published in 2013 an opinion article by Gene J. Koprowski titled “Should Muslims Be Allowed to Pray in Public Schools?” Michigan Says ‘Yes’. This article condemns a Michigan school system’s decision to include Muslim prayer room. Koprowski calls it a violation of due process, freedom of religion, and equal protection. Koprowski writes from the conservative Christian view, and cites a lengthy list of ways in which Sharia Law is sneaking into American legislation through litigation in Michigan, which in turn, he argues, is making Christians in suburban Detroit second-class citizens. (http://www.christianpost.com/news/should-muslims-be-allowed-to-pray-in-public-schools-michigan-says-yes-98695/)

A similarly conservative voice comes from a parents in suburbs of Georgia, where students in Walton County are being taught about Islam in their public classrooms. A concerned parent resents religious symbolism of at least Islam in his child’s classroom. This parent represented a group of parents with a similar sentiment. He said to a reporter, “My daughter had to learn the Shiad, and the five pillars of Islam, which is what you learn to convert, but they never once learned anything about the Ten Commandments or anything about God,” said parent Michelle King. WSB-TV2 aired a story on their station about the controversy in September of 2015. (http://www.wsbtv.com/news/local/parents-upset-kids-taught-islam-school/27036175)

The following are political cartoons addressing the tension surrounding religious symbolism in American public schools.

Political cartoons from: (http://funny-lover.com/)

The Washington Post, “School Prayer Is Dealt a Blow” and “Texas Prayer Case Seen as Kickoff to Bigger Issue for Court” (2000): This nationally-renowned Washington, D.C. paper wrote about the Santa Fe Independent School District case that called into question religiosity in schools. This piece rightly analyzes the social and geographic context surrounding this case, rather than considering the facts of the case in isolation. They highlight the majority Christian population in Texas and their dedication to a “blessed” environment. (http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/articles/A23366-2000Jun19_2.html)

New York Times, “Universal Faith” by Noah Feldman: Religion can have a place in public schools, especially to offer American students a much-needed education on international religions. It just can’t be for believers alone. Feldman also writes of an idea he calls “dual use” which is extremely important. He writes that secular and religious uses may not always be clearly delineated, and that “the state may expend resources to accommodate activities that are religious in the eyes of the believers as long as those activities can still be performed by the general public that interprets them as secular.” (http://www.nytimes.com/2007/08/26/magazine/26wwln-lede-t.html)

A popular online business-news publication IBT wrote about a California schoolsystems that teached world religions within the classroom. Journalist Ismat Sarah Mangla quotes a local Modesto, California teacher who stated, “Knowing about world religions isn’t some kind of multicultural thing… in a shrinking world, an awareness of the religious beliefs around the world is a necessity.” In other words, teaching is not preaching, and Mangla writes that teaching about religion is deeply influential. Some parents, Mangla noted, voiced discomfort about their child learning about Islam in a public school. The photo below was featured in Ismat’s article. It displays overt religious symbolism for apparently secular educational use.(http://www.ibtimes.com/teaching-islam-public-schools-why-fear-religious-education-underscores-need-it-2173645)

Other Diverse Artifacts / Exhibits

The U.S. Government’s website explains U.S.-French relations as allies: “The United States and France established diplomatic relations in 1778 following the United States’ declaration of independence from Great Britain, and France provided key assistance to the United States as an ally during its war of independence.” (http://www.state.gov/r/pa/ei/bgn/3842.html)

The United States Department of Education released a letter on December 31, 2015 in response to an international refugee crisis in Syria and abroad. Former Secretary of the Department Arne Duncan and current Secretary John B. King, Jr. urged American public school workers and teachers to actively pursue a religiously inclusive classroom in light of potential harassment based on religion. Together, they write,

“In response to recent and ongoing issues, we also urge you to anticipate the potential challenges that may be faced by students who are especially at risk of harassment—including those who are, or are perceived to be, Syrian, Muslim, Middle Eastern, or Arab, as well as those who are Sikh, Jewish, or students of color. For example, classroom discussions and other school activities should be structured to help students grapple with current events and conflicting viewpoints in constructive ways, and not in ways that result in the targeting of particular students for harassment or blame… A focus on these protections, while always essential, is particularly important amid international and domestic events that create an urgent need for safe spaces for students.”

This suggestion is very similar to the release that Najat Vallaud-Belkacem, the Minister of The French Ministry of National Education, put forth in June of 2015. Despite France’s implication of complete lack of presence of religion in the public classroom, or laicite, the Minister urged public school workers to actively mobilize in the pursuit of inclusion, something she calls “school-based intervention”. Below is a translation from French to English, provided by the French Ministry of Education’s own website.

“It is your responsibility to ensure that the School remains at its highest level of requirement missions inclusive education for all children, without distinction of acquisition by all republican values, respect for the freedom and dignity of others, tolerance, openness to others…. the prevention of racism and anti-Semitism must base education projects, be at the heart of school life…The successful implementation measures of this plan implies a mobilization of all government departments, local authorities and local institutions, civil society and citizens. The territorial educational projects will seek to develop the initiatives against racism and anti-Semitism within their shutters secularism and citizenship.”

The French Minister of Education, Najaf Vallud-Belkacem has extensive writings on laicite on her own website that expand on the release above: (http://www.najat-vallaud-belkacem.com/tag/laicite/)

For the sake of convenient comparison, I have kept these two above sources together in this research guide.

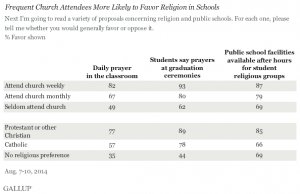

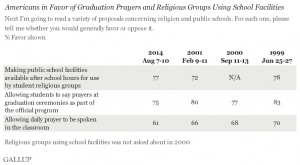

Similar to the French source “Laïcité in practice: the representations of French teenagers”, Gallup conductive quantitative research on American sentiment about religious symbolism in American public schools. These polls were conducted on adults over the phone in all fifty states and the District of Columbia. The margin of sampling error is plus or minus four percentage points at the 95% confidence level. Below are some of their key findings.

To view these images from the source for better quality: http://www.gallup.com/poll/177401/support-daily-prayer-schools-dips-slightly.aspx

From this research and other studies, Gallup concludes that a majority of Americans identify with a religion and see faith as a way to solve the worlds problems. Those following Christianity are in the majority in America. Their findings show a slight dip in support for daily prayer in public schools since 2001, a majority of Americans still do favor this idea. A much larger number of Americans said that they want religion to be a part of graduation ceremonies.

I have carefully selected a collection of books and scholarly articles that I believe offer the strongest insight into the topic.

Secondary Sources

Books

The Praeger handbook of religion and education in the United States: This two-colume book is a hard-hitting, informative source explaining the history of religion’s place in American schooling since the birth of the nation. The textbook opens with an essay that surveys the relationship of religion to elementary and secondary education from the 1600s to the present. The meat of this book is 175 entries written by more than 40 scholars with national reputations that cover a wide range of topics related to religion and education, both in the past and the present. It explains all relevant United States Supreme Court decisions from 1815 to present. It writes in depth about controversies of religion in public schools, what legal, religious, and educational associations partake in this debate, what role religion has in American public curriculum (especially for K-12), and movements that have affected the history of this debate overtime.

“The Bible and The Schools”, by William Douglas: Written in 1966, Douglas writes that the American people are at heart a religious people. He writes that the nation is one that is indeed “under God”. And being predominately a Christian people, he asserts that the law should reflect the protection of that religious majority. Douglas’ faith-based outlook defends the separation of church and state from the point of view of “the spirit of Christian love” and in support of “train[ing] American students in an atmosphere that is free from parochial, sectarian, and separatist influences,” and in support of “patriotic heritage that transcends all differences among people.”

“Religion and the public schools: The legal issue” by Paul A. Freund, and “Religion and the public schools: the Educational Issue” by Robert Ulich: Asserts the need for education about religion or about the history of religions. They write that the inclusion of such courses by “competent teachers” could help fight the widespread ignorance of religious tradition, only if taught with the utmost principles of objectivity and comprehensiveness. This book is written with a slight partiality for Christianity in America, but shows makes a solid attempt at objectivity, making is useful for my analyses.

Exporting Freedom: Religious Liberty and American Power, Anna Su: One chapter of this book comments on French-American international relations in the early 1900’s under the leadership of Clemencaeu and Wilson. Clemencaeu was quoted as saying that working with Wilson on the 14-points (to guarantee human rights and religious rights internationally) was like “working with Jesus Christ”. While America governs with freedom of religion in mind, France protects freedom of religion by governing with religion out of mind.

Scholarly Articles

A scholarly article from Georgetown University called “Church and state in France and the United States” by Jean Baubérot explains the genuine ideological similarities of French and American secularism and laicite, but that the legislation to implement religious freedoms at their core wrangles them incorrigibly. This article is from February of 2013. (https://www.onfaith.co/onfaith/2013/02/21/church-and-state-in-france-and-the-united-states/11415)