by Maddi Brady

Religion and State in Communist China

Despite Communist rule since 1949, China has maintained its vibrant spirituality and religiosity for the past 7 decades. The purpose of this research guide is to understand the complexity of religious life in China and its historic relationship with an atheist state.

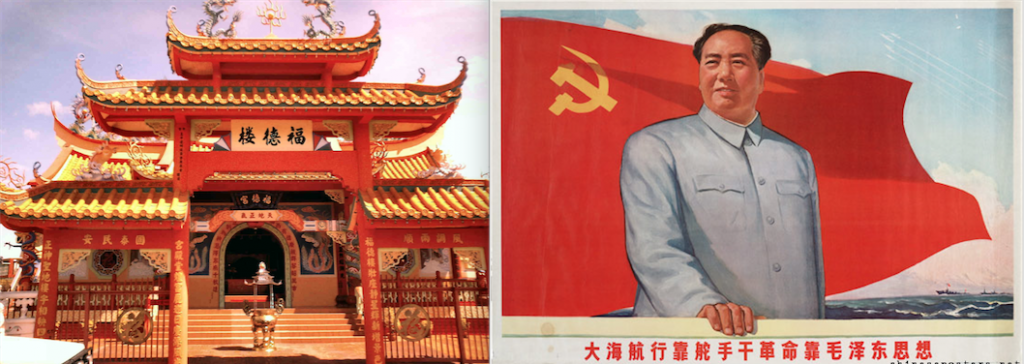

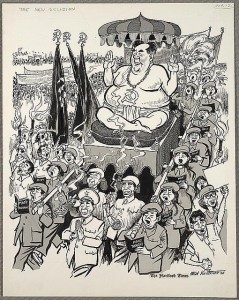

China is the largest country in the world by population, and its people practice a diverse range of ancient Chinese worship to imported Western regions and Islam. The first section of this guide will provide an overview of spiritual worship, religious practices and important religious sites in China. These sources will also provide information on the demographical distribution of religion, social structure of religious communities and religious-ethnic minorities.

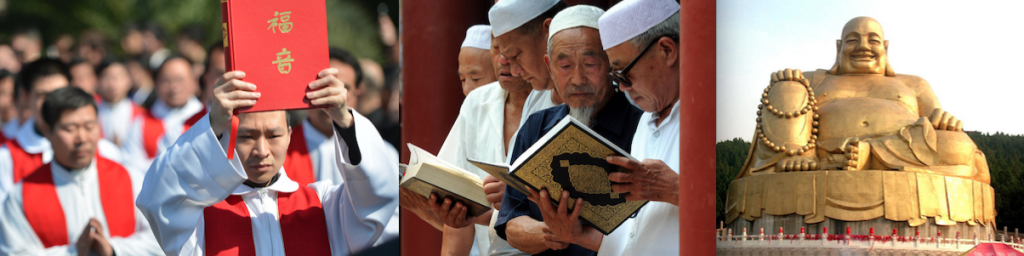

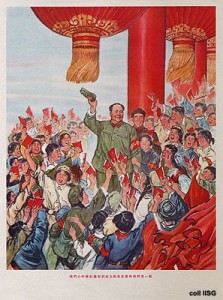

The following two sections of this guide will provide the official legal framework for religious freedom and state policies toward religion. The state’s policy approach to religion changed drastically from the Mao Zedong Era (1949-1976) to the Reform Era following Mao’s death. However, both Mao and Reform Era leadership utilized religious toleration to meet their political purposes. In alignment with Leninist-Marxist Communism, Mao cracked down on religion to elevate his political status, which in turn generated the Cult of Mao. On the other hand, Reform Era leadership opened up religious worship in the 1980’s to control threatening groups and prevent them from going underground.

Today China is experiencing an increased frequency of public protests and a major upsurge in religion, specifically Christianity. Also, religious sites and temples are an important part of the Chinese tourism economy.

How can we explain this seemingly paradoxical coexistence of religion and communism? How can China truly consider itself to be an ideologically Communist State in Marxist terms with its current policies?

Religion in China

Context

Stockwell, Foster. Religion in China Today. Beijing: New World Press, 1993.

- This book offers a broad overview of ancient, Taoist, Buddhist, Muslim, Catholic, Protestant and Orthodox sites in contemporary 1990’s China. The purpose of this book is to educate a Western population on the general state of religious life in China as a visitor’s guide. Stockwell’s methodology involves interviews with Chinese religious leaders and both information and statistics from the state’s various Religious Affairs Bureaus and Cultural Bureaus. He claims to have used a critical lens upon consulting statistics from his later two sources. He counters the notion that China does not have a vibrant religious life, despite being a Communist nation with outstanding evidence.

Goossaert, Vincent. “The Social Organization of Religious Communities in the Twentieth Century” In Chinese Religious Life, edited by David A. Palmer, Glenn Shive and Phillip L. Wickeri, 172-190. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2011.

- Goossaert’s chapter tracks the ideological thought change during the 20th century from spirituality and worship to institutionalized religion. Specifically, he discusses the spiritual communities that have existed in China for centuries – Buddhism, Daoism and Confucianism, and the 20th century integration of Christianity and Islam into Chinese society. He offers specific demographic statistics on “Religious Adherent, as Percentage of the Population”. Goossaert’s main argument is that modern regimes have tried to disqualify and suppress the old religious institutions – local communities and temple worship. These efforts have failed because local religious communities have “resisted, adapted and are thriving anew”.

Shive, Glenn. “Conclusion: The Future of Chinese Religious Life” In Chinese Religious Life, edited by David A. Palmer, Glenn Shive and Phillip L. Wickeri, 241-253. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2011.

- Shive’s conclusion in Chinese Religious Life sums up key cultural, ideological and institutional shifts to religion in China. He argues that Chinese religion is different from Western region in that it does not make “claims for exclusive” truth rather it helps people cope with the everyday. He states that as religion has become secular, it has been redefined as “culture” and “intangible heritage”, which is what makes it more officially acceptable. He attributes the revival in religion to a possible desire for collective Chinese historical identity. He compares the American doctrine of “separation of church and state” to the Marxist systems that has “waxed and waned its tolerance for religion”. This chapter summarizes and lists key points from previous chapters in the book.

Tam, Wai Lun. “Communal Worship and Festival in Chinese Villages” In Chinese Religious Life, edited by David A. Palmer, Glenn Shive and Phillip L. Wickeri, 241-253. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2011.

- In this chapter, The authors provide a Chinese idiom, “Every five or ten miles, local customs are not the same” highlighting the cultural and religious diversity in rural China. Besides the 5 state sponsored religions in China, most rural Chinese worship ancestors, practice rituals, hold festivals and practice Fengshui. The line between official and not is blurred; however, people have been practicing these traditions for centuries. Are these practices religion, worship or culture?

Religion and Ethnic Minorities

Wickeri, Philip and Yik-Fai Tam. “The Religious Life of Ethnic Minority Communities” In Chinese Religious Life, edited by David A. Palmer, Glenn Shive and Phillip L. Wickeri, 50-66. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2011.

- Ethnic Han Chinese dominate China’s population; however, a diverse number of ethnic minorities live in China, so what religions do they practice and how are they treated? The authors offer demographics citing what types of ethnic minorities live in China and where they predominantly live. They argue this religious pluralism amongst official ethnic minorities offers positive intereligious dialogue in a global world, and on the other hand more opportunities for tension and conflict. As evidence, the authors offer case studies including the Dongba month the Naxi People, Tibetan Buddhism, Islam among the Uyghurs and Christianity among the Miao.

Religious Freedom: The Legal Framework

Constitution of the People’s Republic of China (2012)

- Chapter II, Article 36 of the Constitution of the People’s Republic of China provides China’s legal framework for religious freedom and activities. Specific language promises “freedom of religious belief”, which only guarantees freedom of “belief” – not worship or practice. The State cannot compel any individual to believe, not believe in religion or discriminate against religious believers, which again uses inconsequential language. Article 36 protects “normal religious activities” as long as they do not “disrupt public order, impair the health of citizens or interfere with the educational system of the State”. Likewise “normal” religious activities may be interpreted broadly. Activities that interfere with public order, health or education could mean anything or everything in a state led by a Communist, Atheist party.

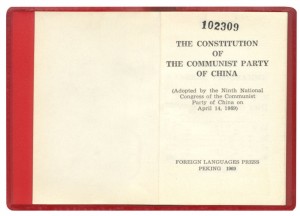

Constitution of the Communist Party of China

- The Communist Party of China has ruled China since 1949, so understanding their fundamental outlook on religion is essential to this topic. The text does not specifically mention god, religion or Atheism; however, Atheism is implicitly implied in the “General Program” section and Chapter I. The text reiterates that Chinese communism embodies a “Marxism-Leninism”, an ideology founded on Atheism.

Horsley, Jamie. “The Rule of Law: Pushing the Limits of Party Rule” In China Today, China Tomorrow: Domestic Politics, Economy and Society, edited by Joseph Fewsmith, 51-68. New York: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, 2010.

- Communist China did not have a legitimate legal framework until the 1978 Third Plenum of the Eleventh Central Committee. In this chapter, Horsley lays out China’s modern legal framework — established legal goals, legislative and rule making institutions, the court system, lawyers, law as an instrument to restrain power and China’s open government. Despite successful legal reform, Horsley notes three shortcomings: “broad compliance with and enforcement of law, and holding lawbreakers accountable”. He attributes these problems to the Communist Party’s “extralegal status”, and the “tension between promotion of greater rule of law and one-party rule [that] permeates the entire legal system”. This secondary source is very helpful to understand the past 35 years of China’s legal history and contemporary legal climate.

- Xiong’s article briefly describes China’s religious freedom legal history and current framework. He discusses the five legal religions: Buddhism, Taoism, Islam, Catholicism and Protestantism, and explains the opening up on the legal system in 1978. In section 2(b), he cites specific religious freedom laws as the specific legal framework. In section 3, he discusses the government bodies that administer religion in China. The purpose of this article is to demonstrate how foreign religious bodies may lawfully promote their ideas; however, he gives an insightful description on the history and current legal approach to freedom of religion in China.

State Administration for Religious Affairs Website

- This is the Chinese State’s official website for the State Administration for Religious Affairs. This is relevant in reviewing the state’s current objectives purposes.

State Policies on Religion

Maoist China (1949 – 1976):

Religion as a Political Weapon: Anti-Religious Propaganda, Cult of Mao

Bush Jr, Richard. Religion in Communist China. Nashville: Abingdon Press, 1970.

- This book gives a broad overview of the Communist party’s historical approach to Protestantism, Catholicism, Islam, Buddhism and folk religion. In terms of methodology, Bush wrote this book without every visiting China and based his research on books and articles, which is not entirely persuasive. For this reason, but majority of the book is focused on policy and Christianity. His book presents a matter of fact history regarding the interaction between Western religions and Chinese policies.

MacInnis, Donald E. Religious Policy and Practice in Communist China; a documentary history. New York: Macmillan, 1972.

- In this book, MacInnis compiled 116 Chinese primary source materials on the topic of religious policy and practice in Communist China. These sources include Chinese press pieces related to “China’s leaders, theoreticians and other questions of religion”. The purpose of this volume is to demonstrate how religious policies were in fact practiced. MacInnis see his book as a sequel to Bush’s Religion in Communist China, so it is valuable to see the source material Bush used. These sources include the following: Mao Tse-Tung and Religion, Statements by Party, State and Leaders, Chinese Theoreticians Debate Religious Policy, Theory and Tactics, Patriotism and Untied Front, Religious Policy and National Minorities, Religion and Imperialism, Self-Reliance and Autonomy, Religion and Feudalism, Superstition, Complaints Against Religious Policy in Practice and more.

Tse-tung, Mao. “Overthrowing the Clan Authority of the Ancestral Temples and Clan Elders, the Religious Authority of Town and Village Gods, and the Masculine Authority of Husbands.” In Chinese Religion: An Anthology of Sources, edited by Deborah Sommer, 309-316. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1995.

- This 1927 primary source document was written by Mao prior to the Communist party’s official takeover during early Communist ideological propaganda campaigns against religion (1920’s and 1930’s). This excerpt was taken from Mao’s “Report on an Investigation of the Peasant Movement in Hunan”. This text describes Mao’s efforts to organize peasants by harshly condemning religion as “vulgar superstitions propounded by local tyrants for their own selfish ends.” In conversation with peasants, he argues that after centuries of worship, the gods have not helped peasants overthrow their lords. According to this text, the peasants responded by “roading with laughter.”

Chang, Jung. “Father Is Close, Mother is Close, but Neither Is as Close as Chairman Mao.” In Chinese Religion: An Anthology of Sources, edited by Deborah Sommer, 303-307. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1995.

- In this primary source memoir from her 1991 book, Wild Swans: Three Daughters of China, Chang describes her experience growing up under The Cult of Mao. She had a typical Maoist China upbringing and life story as a peasant, steelworker and electrician. She was born in 1951 and lived through the Cultural Revolution in 1966-1976. The memoir describes how worshiping Mao became the new form of religion and the state “created a people who had no thoughts of their own”. Mao did this by “sowing the seeds for his own deification” by occupying a seemingly “selfless” “moral high ground”.

Valtman, Edmund. “The New Religion.” Ink, tonal overlay on paper, The Hartford Times, October 13, 1966.

- This American news comic illustrates notion of the Cult of Mao. He demonstrates how citizens under Mao still read rudimentary texts, worship symbols, chant and praise a higher being. Communist ideology replaced spirituality, the hammer and sickle have replaced the Eight Characters and Mao is the new Buddha. This image satirically illustrates the ideas described in Chang’s memoir.

Chinese Propaganda from the International Institute of Social history

- This is a Chinese propaganda poster from 1968 demonstrating Mao Zedong and his “close comrades”. The comrades wave their red books at Mao, who is elevated above the crowd, which demonstrates the Cult of Mao personality. This piece is interesting when juxtaposed next to the American Valtman comic.

Clark, Anthony. “China’s Modern Martyrs: From Mao to Now.” China’s Modern Martyrs: From Mao to Now, Catholic World Report. March 24, 2014.

Unknown Artist, Newspaper cartoon from the Jiefang ribao [Liberation Daily], 13 October 1951.

- Jiefang Daily is a daily newspaper of the Shanghai Committee of the Communist Party of China. This image depicts a priest holding an image of an American soldier, Korean soldier and the Virgin Mary – three main enemies of Mao’s regime in the 1950’s. The side caption reads: “The people resist America and support Korea’s patriotic movement—as they [Catholics] assert: ‘The Holy Mother watches above the American and Korean militaries”.

Unknown Artist, Newspaper cartoon from the Jiefang ribao [Liberation Daily], 12 October 1951.

- In this image, a Chinese priest wearing Nazi swastikas is being punched out of a church by an arm that reads, “Patriotic Catholic”. This piece may be anti-Catholic or just generally anti-Christian, anti-Western and anti-imperialist.

— — —

Reform Era (1980’s – present)

Religion: a political tool + major threat to the state

- In this article, Goldman offers a brief history of religion during Maoist China (1949-1976). Most importantly, she provides a contemporary account of religious reform and policy, from a 1986 perspective – 10 years after Mao’s death. During his last decade of power, known as the Cultural Revolution (1966-1976), Mao cracked down against religion practices, so citizens worshiped secretly. Goldman argues that post-Mao “reform” leadership was more tolerant of religious practices for political purposes; the government could better control public over private worship.

Weller, Robert and Sun Yanfei. “Religion: The Dynamics of Religious Growth and Change” In China Today, China Tomorrow: Domestic Politics, Economy and Society, edited by Joseph Fewsmith, 29-50. New York: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, 2010.

- In a detailed overview of modern Chinese religion, Weller and Yanfei discuss the spectrum of religiosity in China from “worship” to “religion” and unofficial to state-sanctioned. Weller and Yanfei focus on Temple Religion, Buddhism and Protestantism as case studies to demonstrate how religion and state interact. They also discuss the state’s official policy stance toward religiosity in addition to the state’s actual response. Weller and Yanfei demonstrate that politics and religion are extremely interconnected in China, and the Communist Party tolerates religions differently depending upon their political utility or threat.

Laliberté, André. “Contemporary Issues in State-Religion Relations” In Chinese Religious Life, edited by David A. Palmer, Glenn Shive and Phillip L. Wickeri, 191-208. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2011.

- Laliberté describes how the Chinese state has organized patriotic associations for each of the five major religions at national and local levels. The state religious affairs offices at different times and in different places in China may loosen or tighten their control over registered religious bodies (p. 250).

- In this interview, Yang offers insights on why and how a paradoxical coexistence between an Atheist Communist State and vibrant religious society in modern day China. This source is particularly relevant in order to understand the contemporary 2016 dynamic between state and religion. According to Yang, the state sees the important social and psychological value to religion for enhancing the morality of the nation. He also describes the geographic and demographic breakdown of religious groups, and states that China will become the largest Christian nation by 2030. Yang discusses the relationship between nationalism, consumerism and religion in modern day China, and how this is particularly problematic with Buddhism. Most importantly, he notes that in 2016 the Chinese government has severely cracked down on religion, but this is bound to fail because many party members themselves are religious.

Albert, Elenor. “Religion in China.” Council on Foreign Relations. June 10, 2015.

- This article gives a contemporary update on the current status of different religious groups – official and unofficial – in China, today. The article also demonstrates the state’s current legal standing, policy and approach to different religions. Through quantitative research, the piece demonstrates a rise in religiosity in China and highlights the foreseeable conflict between state and religion.

Contemporary Issues

Rise in Popular Protest

Perry, Elizabeth. “Popular Protest: Playing by the Rules” In China Today, China Tomorrow: Domestic Politics, Economy and Society, edited by Joseph Fewsmith, 11-28. New York: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, 2010.

- Perry’s key argument is that the Communist State responds to popular protests as a means to placate the people on a localized level. Surprisingly, the frequency of protests has escalated ten-fold since the 1989 Tiananmen Square mass demonstration — from 8,700 protests in 1993 to 87,000 protests in 2005. Perry attributes this rise to a “rights consciousness” discovered during China’s post-Mao reform era as a possible reason. She explains that this “rights consciousness” comes from 150 years of Western, Christian influence, but also the state itself “publicizing and propagandizing the importance of ‘legal rights’”. Perry’s key argument is that public protest helps the state in two ways — limits corruption and prevents driving discontented groups underground. As long as the state responds “sympathetically yet shrewdly” to protests, the political and legal system is strengthened. In this chapter, she evaluates protests in Mao’s China, rural Reform Era protests and urban Reform Era protests as evidence for her argument.

State, Religion and Tourism

Oakes, Tim, and Sutton, Donald S., eds. Faiths on Display : Religion, Tourism, and the Chinese State. Blue Ridge Summit, US: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, 2010.

- This book highlights different regions of China and the associated tourism activities. The authors indicate different reasons for tourist activities and the implications on local economies, local communities and religion itself. They also focus on how the state actually builds temples, which creates tension with secular official ideology.

More sources to be investigated…

Yang, Fanggang. Religion in China: Survival and Revival Under Communist Rule. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2011.

Dillon, Michael. Religious Minorities and China. London: Minority Rights Group International, 2001.

Religion Under Socialism in China by Zhufeng Lou (1991)

Notes:

In the original 1949 constitution, freedom of religious “belief” was granted in article 88, not 36