by Haley Witsell

INTRODUCTION

Prior to the last several decades, French Revolutionary historiography rarely focused on journalism as a key player in the Revolution’s initiation or development. Instead, historians typically relied on the French Revolution’s publications as research tools: primary source materials providing chronological and sociological assistance. Reasons for the recent proliferation in journalism-focused French Revolutionary research include a divergence from the classical Marxist interpretation of the Revolution, in addition to a stronger focus on Revolutionary culture and its relationship to politics. Studies of the French Revolution’s dynamic press output now enjoy the spotlight due to changing perspectives in historiographies: shifting focus away from the socio-economic and into the “politico-cultural.” This puts the problem of culture–in this case, pertaining to public opinion through the press–at the center of the French Revolution’s history.

Execution of Louis XVI in what is now the Place de la Concorde, facing the empty pedestal where the statue of his grandfather, Louis XV, had stood. (1793)

This annotated bibliography provides resources covering the French press from the last days of the Old Régime into the French Revolution, and a little beyond, into revived press censorship under Napoleon. The annotated material includes primary sources focused on the era’s most influential newspapers and their contributions to a nation in flux. A thorough selection of secondary sources is also included, providing extensive research on the Revolution’s journalistic influences before, during, and after the French Revolution. This bibliography excludes the “other” side of publishing (i.e., the highly popular sensationalistic fiction of the era), to focus primarily on its journalistic endeavors–arguably the more publicly influential of the two publishing forms in terms of impacting the French Revolution.

The secondary sources together cover an extensive range of topics concerning the revolutionary press: its journalists, publishers, and readers; the printing process, format, and design; subscription prices, press runs, and profits; typical newspaper coverage showcasing various political angles; and ways in which the revolutionary press differed strikingly from that of the Old Régime and the subsequent Napoleonic period. Some texts also explore the newspaper’s crucial role in creating new identities for workers, women, and members of the middle classes that redefined Europe’s public sphere during and following the French Revolution. The question as to the press’s significance in the rise and fall of the Revolution is debated throughout these secondary sources and will proceed indefinitely. Hopefully this project’s resources will spark creative interpretations and inventive perspectives on the matter of the press in the French Revolution.

_________

This annotated bibliography is organized by three general points of study: The Press in Old Regime France; The Press in Revolutionary France; and The Legacy of the Press in the French Revolution. Within these sections, all sources will be secondary texts and journals. The primary source list (located in the second section, “The Press in Revolutionary France”) provides links to electronic resources. The primary sources are a selection of the era’s most influential newspapers, with annotations and links to archived copies. Each section below is annotated as a whole, as opposed to treating every source individually (seeing as the sectional filters indicate each resource group’s general focus). However, some exceptions apply as noted in cases where a source is significantly different from those in the same section, thus requiring further details.

Note: For the purpose of this annotated bibliography, the “French Revolutionary” years of focus extend prior to and just following the Revolution. France’s journalism from roughly 1788-1810 will be considered as the timeline for this project.

ONLINE RESOURCES

The following are the two essential electronic databases for this bibliography. Each includes primary and secondary resources, particularly useful is the abundance of open-access newspapers and journals in their original formats.

Gallica, Bibliothèque nationale de France.

Gallica is the digital resource for France’s national library, including other affiliated archives.

THE PRESS IN OLD REGIME FRANCE

The following resources provide a look at the French press prior to the Revolution, in the Old Regime (or l’Ancien Régime), including the literary privileges, censorship, and various other monarchical limitations imposed upon the press.

TEXTS

Cobban, Alfred. A History of Modern France . Vol. 1: 1715–1799 . Middlesex, Eng.: Penguin Books, 1963.

Darnton, Robert. The Business of Enlightenment: A Publishing History of the Encyclopédie, 1775–1800 . Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1979.

As a general note, Robert Darnton is a leader in the historiography of the French Revolution, particularly in consideration of the press. Many of the historians included in this bibliography are directly influenced by him. This book is included because the publishing output from the Enlightenment’s philosophs (such as Rousseau) is often considered to be a significant factor in the perspectives leading up to and lasting throughout the Revolution.

Darton, Robert. The Literary Underground of the Old Regime . Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1982.

Another one from Darnton’s extensive output of Revolutionary print-related historiography. This one is useful in understanding the more radical, “underground” happenings in the publishing world preceding the Revolution, and thus having considerable influence leading into the Revolution as well.

Gelbart, Nina Ratner. Feminine and Opposition Journalism in Old Regime France: “Le Journal des Dames .” Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1987.

JOURNAL/EXCERPT

“Enlightenment Epistemology and the Laws of Authorship in Revolutionary France, 1777–1793.”Representations 30 (Spring 1990): 109–137.

This excerpt offers a general overview of the changing regulations on censorship and authorial rights in the Enlightenment and Old Regime, leading into the Revolution.

THE PRESS IN REVOLUTIONARY FRANCE:

PRIMARY SOURCES

Journal de la Mode et du goût, ou Amusemens du salon et de la toilette

(Journal of Fashion and Taste, or Entertainments of Lounge and Dress)

Despite the political and social upheaval of the Revolution, Parisians still looked forward to entertainments such as fashion, music, and literature. Francois Buisson’s Journal de la Mode et du gout was one of the most popular journals during the Revolution, and one of the first fashion journals upon its introduction in the 1780s.

M. Le Brun. Edited by Francois Buisson. Journal de la mode et du goût, ou Amusemens du salon et de la toilette Vol. 4, no. No. 1-No. 4 (February 25, 1790). Bibliothèque nationale de France.

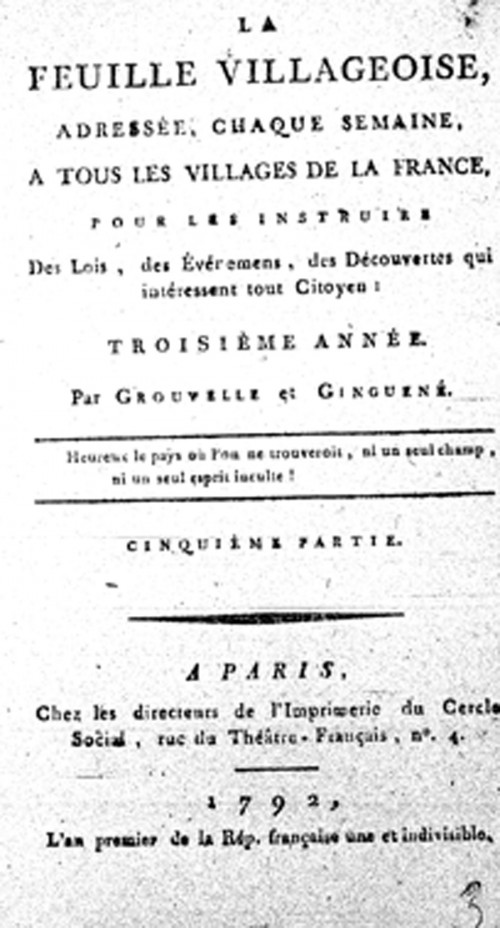

La feuille villageoise (The Village Leaf)

La Feuille villageoise : adressée, chaque semaine, à tous les villages de France, pour les instruire des loix, des évènements, des découvertes qui intéressent tout citoyen, proposée par suscription aux propriétaires, fermiers, pasteurs, habitans et amis des campagnes.

or,

The Village Leaf: sent each week to all villages of France, to instruct the laws events, discoveries relevant to every citizen, proposed by subscription to owners, farmers, pastoralists, rural inhabitants and friends.

Pierre-Louis Ginguene published the Feuille Villageoise, a periodical arguably most successful at narrowing the disparity between rarified and mass cultures. He wanted high culture to be accessible to the populace.

La feuille villageoise ., 1795 1790, Oct. 1792-April 1793 edition. Collection Les archives de la Révolution française. Bibliothèque nationale de France.

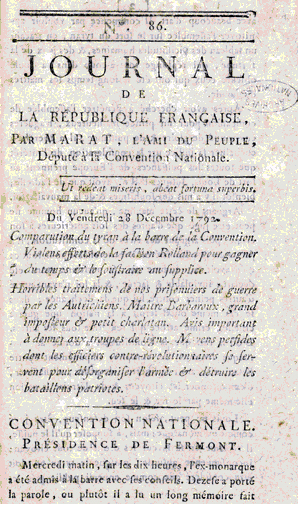

L’Ami du peuple (Friend of the People)

L’Ami du peuple, or Friend of the People, was a radical Parisian newspaper under the singular direction of Jean-Paul Marat. This newspaper is significant, as it was in many ways the public voice of the sans-culottes and the radical Parisian sections. Running from mid-1789 until the day after Marat’s death in July of 1793, the paper is a valuable source for analyzing the development and progression of the radical Left from the waning days of the ancien régime to the first summer of the National Convention. Aside from its textual content, the paper is noteworthy as it continued to run while Marat was a deputy of the National Convention, highlighting the complete absence of contemporary notions of journalistic objectivity.

Image of edition N˚ 86: opens with Marat excoriating his political opponents in the Convention.

Marat, Jean Paul, and A. (Auguste) Vermorel. Œuvres de J.P. Marat (l’ami du peuple) recueilliés et annotées par A. Vermorel. Paris: Décembre-Alonnier, 1869.

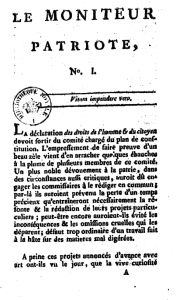

Regarding the image to the left and the citation below, Le Moniteur patriote was the original title of L’Ami du peuple. This was its first issue.

Marat, Jean-Paul. Le Moniteur patriote. August 1789, No. 1 edition. Gallica, Bibliothèque nationale de France.

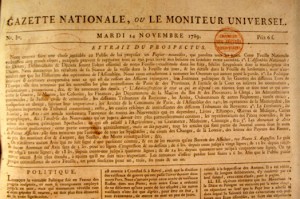

Gazette Nationale ou Le Moniteur Universal

(The National Gazette or The Universal Monitor)

Le Moniteur Universal holds a privileged position for scholars of the French Revolution, for, in addition to its focus on both domestic and international matters, it detailed to an extraordinary degree the procès-verbal of the National Convention. Further, it would become the principle propaganda machine of Napoleon and many other successive regimes.

Le Moniteur Universal holds a privileged position for scholars of the French Revolution, for, in addition to its focus on both domestic and international matters, it detailed to an extraordinary degree the procès-verbal of the National Convention. Further, it would become the principle propaganda machine of Napoleon and many other successive regimes.

Panckoucke, Charles-Joseph, ed. Gazette nationale ou le Moniteur universel.Nov. 24, 1789 – Dec. 31 1810. Paris, 1789. 1810 1789, Nov. 24, 1789 – Dec. 31 1810 edition. Bibliothèque nationale de France.

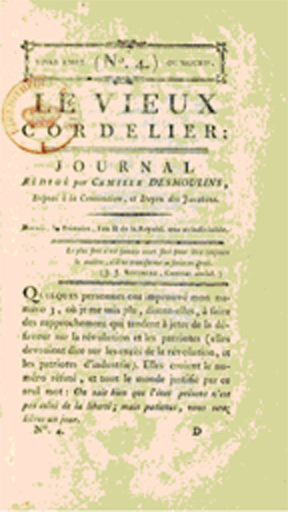

Le Vieux Cordelier

(The Old Cordelier)

(The Old Cordelier)

Le Vieux Cordelier, or, The Old Cordelier, was a well-known journal during the Reign of Terror. Published intermittently from late-1793 until early 1794 by the conventionnel Camille Desmoulins, the journal was the public voice of the Dantonists.

In N˚ 4, at the right, Desmoulins attacks the revolutionary committees for their unnecessary severity. Why, he asks, has clemency become a crime in the Republic? Desmoulin would pay with his life for speaking out against the committees; his execution in 1794 was likely decreed by the revolutionary tribunals in order to silence one of the principle voices of moderation during the Terror.

Desmoulins, Camille (1760-1794). Le vieux Cordelier de Camille Desmoulins, seule édition complète. précédée d’un Essai sur la vie et les écrits de l’auteur / par M. Matton aîné. Edited by Matton, M. Paris: Ebrard, 1834. Bibliothèque nationale de France.

Le Père Duchesne (Father Duchesne)

Le Pere Duchesne was an extremely radical newspaper during the French Revolution, published and edited by Jacques Hébert. Hébert published 385 issues from September 1790 until March 13, 1794; he was killed by the guillotine just eleven days later. The title was revived many times later (with no affiliation to Hebert’s original), usually during periods of revolt.

Below: Cover of issue no. 25 of Hébert’s Le Père Duchesne—Against the “Indissolubricity” [sic] of Marriage and His Motion for Divorce

Charles Brunet published a compilation of Le Père Duchesne issues, accessible here. Below is an English translation of the extended title. Below that, is the bibliographic information in French.

Father Duchesne Hébert, or historical and bibliographic record of this newspaper during the years 1790, 1791, 1792, 1793 and 1794; preceded the life of Hébert, author, and followed by an indication of his other works.

Brunet, Charles. Le Père Duchesne d’Hébert, ou Notice historique et bibliographique sur ce journal publié pendant les années 1790, 1791, 1792, 1793 et 1794 ; précédée de la vie d’Hébert, son auteur, et suivie de l’indication de ses autres ouvrages. Paris: Libr. de France, 1859. Bibliothèque nationale de France

THE PRESS IN REVOLUTIONARY FRANCE:

English: "You should hope that this game will be over soon." The Third Estate carrying the Clergy and the Nobility on its back Français : "A faut esperer q'eu.s jeu la finira bentot" Le Tiers-État portant le Clergé et la Noblesse sur son dos. (1789)

The Revolutionary press acted in many ways as the new political culture’s messenger to the public. The ubiquitous and persuasive powers of the press helped translate the complex Revolutionary happenings to the public. Furthermore, by reporting on and thereby publicizing otherwise isolated Assembly speeches, the press was essential to the Revolution’s emphasis on representative politics. During the Revolutionary era, the newspaper served as unofficial public representation, lending transparency and awareness to government proceedings. Some resources also provide a look at the press immediately following the Revolution, with Napoleon’s empire and the reinstitution of censorship.

TEXTS

Darnton, Robert, and Daniel Roche, eds. Revolution in Print: The Press in France, 1775–1800 . Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1989.

Hesse, Carla. Publishing and Cultural Politics in Revolutionary Paris, 1789-1810. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1991

Hesse’s work focuses a bit more on the publishing side of the French Revolution as opposed to a more journalistic press focus. However, this is very informative on the industry as a whole and its connections with the Revolution before and after.

Hunt, Lynn. Politics, Culture, and Class in the French Revolution . Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1984.

Hunt is another great authority on the press in the French Revolution, as is Popkin, below. Both have contributed to and published their own studies on the cultural-political and journalistic aspects of French Revolutionary historiography. (Naturally, both have collaborated with Robert Darnton as well.)

Popkin, Jeremy D. Revolutionary News: The Press in France, 1789-1799. Durham and London: Duke University Press, 1990.

Popkin, Jeremy D. The Right-Wing Press in France, 1792-1800. Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 1980.

Kates, Gary. The Cercle Social, the Girondins, and the French Revolution . Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1985.

Kennedy, Emmet. A Cultural History of the French Revolution . New Haven: Yale University Press, 1989.

JOURNALS/EXCERPTS

Coffin, Victor. “Censorship Under Napoleon I.” American Historical Review 22 (1916–1917): 228–308.

Cook, Malcolm. “Politics in the Fiction of the French Revolution, 1789–1794.”Studies on Voltaire and the Eighteenth Century [Oxford], no. 201 (1982): 237–340.

“Texts, Printings, Readings.” In The New Cultural History, edited by Lynn Hunt, 154–175. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1989.

Kulstein, David I. “The Ideas of Charles Joseph Panckoucke, Publisher of the Moniteur Universel, on the French Revolution.” French Historical Studies 4, no. 3 (Spring 1966): 307–309.

Panckoucke (the subject of Kulstein’s book) was considered the French “Press Baron”–along the lines of William Randolph Hearst had he been the publisher of a French Revolutionary paper. While Le Moniteur Universel took charge in translating the National Convention’s endless verbiage to the public, it later became a propaganda machine for Napoleon and others.

LEGACY OF THE PRESS IN THE FRENCH REVOLUTION

The following sources offer a variety of perspectives on the lasting effects of the French press in shaping the Revolution’s historiography.

TEXTS:

Darnton, Robert. The Great Cat Massacre and Other Episodes in French Cultural History . New York: Basic Books, 1984.

This cartoon, "Corsican Crocodile dissolving the Council of Frogs," depicts Napoleon's coup d'état of the French government in 1799. Censorship eventually returned in his empirical rule.

Eisenstein, Elizabeth. The Printing Press as an Agent of Change . 2 vols. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1979.

George, Albert J. The Didot Family and the Progress of Printing . Syracuse: Syracuse University Press, 1961.

JOURNALS/EXCERPTS

Foucault, Michel. “What Is an Author?” In Textual Strategies: Perspectives in Poststructuralist Criticism, edited by Josué V. Harari, 141–160. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1979.

“Printing and the People.” In Society and Culture in Early Modern France, 189–226. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1975.