When people ask me what I teach, and I answer “religious studies,” I am always compelled to add that this has nothing to do with theology, and everything with the Humanities. Aside from the fact that I don’t wish to appear religious when I am not, I also want my work to be taken seriously as a kind of “scientific” inquiry; “scientific” here in the sense of the German term Wissenschaft. Humanistic research into the sources, truth claims, and effects of religious beliefs is guided and delimited by the fundamental assumptions of all Humanities, which is that religion is one human form of self-expression, community-building, and world-representing among others. The starting point of academic religious studies is therefor our methodical irreligion.

When we study the so-called “western” religions, the major subject of our research is a legacy of prophetic revelation present in form of texts and claims to their divine origin and authority. Revelation is the subject of our humanistic study of religion. The question I want to consider in the following is whether the fundamental assumption of the humanistic study of religion is adequate for the study of its subject.

To avoid any misunderstanding, let me emphasize that I am not raising this question because I believe in divine revelation in the sense suggested by the plain meaning of our foundational texts. My intention is not to defend the truth claims of any or all religions. Rather, I have come to experience our methodical questioning of the truth claims of revelation as less than self-evident, as in need of its own methodical reexamination. I add, for purely autobiographical self-indulgence, that this question has been with me since I first set foot in the lecture halls of the academy. What justifies our attack on the beautiful world of religious belief?

In order to avoid the aggressive gesture of an attack, some of us prefer to say that their study of the revealed religions “brackets” the truth claims of their subject and deals with religious myths, symbols, and rituals exclusively as “phenomena,” i.e., with experiences represented in linguistic and other forms of symbolic representation. Things as experienced and communicated are always open to critical investigation even as the actual subject of the experience remains elusive. This approach veils any skeptical or negative attitude toward the truth-claims of religion on the part of the investigator behind a screen of methodological limitation: human comprehension as too limited to judge divine realities as such. This was Kant’s solution to the problems of metaphysics, a solution that did not prevent him from making far-reaching assertions about the ethical content of the Christian religion, or on the lack of religious cum moral function of Judaism.

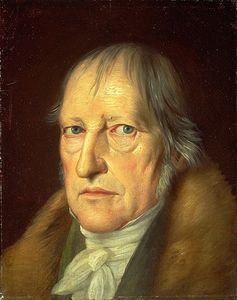

To invoke Kant in this context means to invoke the German Enlightenment. Instead of drawing a clear line between scientific knowledge and religious belief, as did the radical Enlightenment of Voltaire, Toland, Hume, and others, Kant and the German idealists took it upon themselves to interpret religion as a symbolic representation or anticipation of rational truths, in however limited or distorted form. Their starting point as well was the denial of any knowledge of revelation as revelation, in other words, their negative starting point was their lack of belief in revelation as such. If there is no revelation, there is no compelling reason to consider Judaism, Christianity, or Islam as revealed religions or as more or less adequate representations of revealed truths or revealed laws. (The latter difference ought to remind us that the debate on the content and character of Judaism and Christianity is more complicated than what I suggest here. See Mendelssohn, Jerusalem.) They are merely the more or less deficient, or more or less perfect, expressions of the “spirit” (Hegel). Once reduced to the level of humanity, revealed religion is open to be criticized for its all-to-human causes and effects. There is nothing to prevent us from seeing religion as the excrescence of socio-economic forces (Marx), as the means of repression of our natural desires for dominance (Nietzsche) or sexual pleasure (Freud), or means by which we satisfy our need for belonging (Durkheim).

This point of departure for the modern study of religion has been challenged by the “renewal of orthodoxy” (Strauss, Preface to SCR), following the Great War. There is now a clash between two contrary assertions, both of which appear equally grounded in axiomatic assumptions, namely, belief and unbelief, rather than ignorance and knowledge. With Goethe, Strauss argued that these two positions (belief and unbelief) are not equivalent. Only one of them is original, namely belief, whereas the other one is a mere negation of belief, without a constructive first assumption of its own. (I am aware that Blumenberg argues otherwise. Strauss’s overall project may be described as the attempt to retrieve a position where the fundamental difference is no longer that between belief and unbelief but between knowledge and ignorance.)

To reiterate, the point of these considerations is not to defend religion but to draw attention to a fundamental problem of justification that arises from an unresolved and often unstated first assumption we bring to the teaching of religion in the context of the Humanities.

One of our responsibilities as teachers of religious studies in the context of the Humanities is coeval with one of the founding principles of the Humanities, that is, the modeling of habits of critical thinking. Critical thinking requires thought to turn on itself. It asks questions, such as how do we know, and what makes us so certain? The largely forgotten origin of this modern school of critical thinking is the method of doubt, first articulated by Renée Descartes in his Discourse on Method. In order to know, we must subject all of our opinions and assumptions to doubt, so as to arrive at an unquestionable starting point. Descartes argued that this starting point is doubt itself, which leads to the presupposition of our existence as thinking beings, or being grounded in thought. (Note: Strauss points to a difference between opinions, which were the problem addressed by Socrates/Plato, and prejudice, which is our problem, namely, since the advent of our “revealed” religions in the world of human culture, an insight Strauss associates with Maimonides, Guide I, Introduction.)

Subjecting our convictions to doubt means to cast doubt on doubt itself. In this particular case, casting doubt on doubting the reality of revelation, which has turned into an unquestioned conviction. This is not to assert that revelation is “real” in a more acute or different sense than anything else is “real.” (See Hermann Cohen on the “judgment of reality.”) But the methodical subjection of the “real” to an idealist critique, as in Kantian and post-Kantian idealist philosophy, cannot methodologically deny what orthodoxy and neo-orthodoxy assert, namely, that it is perfectly legitimate from “beyond the limits of mere reason” to assert revelation as an actual event, an actual experience, and hence a claim to an absolute obligation. It is this legitimate challenge to the limitation of what can and may be said about revelation that makes it appear problematic to impose an unbelieving (including idealist) framework on the discourse on religious truth that takes place in our classrooms.

To proceed in our approach to questions of God, revelation, and religious beliefs of this kind without taking this challenge of the authority of critique into consideration, means to proceed uncritically.

(To be continued.)

One Comment

trunnion ball valve posted on August 26, 2022 at 2:12 am

Belief, Unbelief, and the College Study of Religion | Michael Zank1661494372