On October 5-6, 2012, the Department of Medicine will celebrate its centennial with a symposium. In planning the agenda of speakers and sessions, the organizing committee left time for questions from the audience. As important as this interaction is, I am reminded of how rare it is to hear a good question after a presentation.

Commonly, the so-called questions are really comments. If forced to abide by the interrogative form, the questioner will add a perfunctory, "Don't you agree?" Other times, the questions are rambling and disconnected from the speaker's main argument. Sometimes I hear very specific methodological questions that interest only specialists.

What all these kinds of questions have in common is that they are more interested in showcasing the asker than eliciting an answer. I was relieved to read that other academics have the same pet peeve. Peter Wood from the National Association of Scholars describes a panel he participated in where none of the questions started with "who," "what," "when," "where," or "how."

In the service of restoring the A and A period to a Q and A, he offers several useful suggestions:

- Have a single point.

- Don't ask clarifying factual details.

- Avoid talking about the question; just ask it.

- If someone else asks your question, put your hand down.

- Resist speaking for an entire category of people.

- At the same time, resist giving your autobiography.

- Add value to the conversation.

The burden to be witty may be too heavy, so just focus on being concise and curious.

A

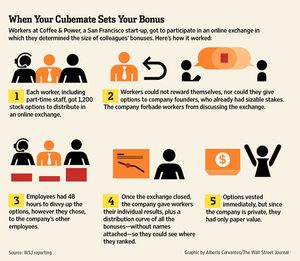

A  As practiced at a coffee shop in San Francisco, employees receive a certain amount of shares that they can distribute to their coworkers, in essence voting for how much they value each other's contributions.

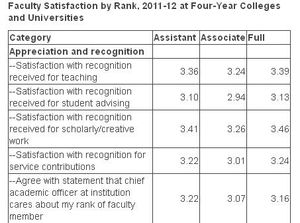

As practiced at a coffee shop in San Francisco, employees receive a certain amount of shares that they can distribute to their coworkers, in essence voting for how much they value each other's contributions. The investigators asked how many ranks are used in universities across 28 countries. It turns out that only India and Italy join the United States in designating three rungs of academic promotion.

The investigators asked how many ranks are used in universities across 28 countries. It turns out that only India and Italy join the United States in designating three rungs of academic promotion. investigators can explain the benefits of their projects and seek funding. So far the projects seem to involve wildlife conservation, which may make for more visually appealing descriptions. But any scientist can take a turn explaining the benefits of their research.

investigators can explain the benefits of their projects and seek funding. So far the projects seem to involve wildlife conservation, which may make for more visually appealing descriptions. But any scientist can take a turn explaining the benefits of their research.