Some common (and perhaps not so common) Moscow sights:

The Russian State Historical Museum (L) and the GUM. These buildings, along with St. Basil's Cathedral (above) and the Kremlin wall border Moscow's Red Square.

The Kremlin as seen from the Moscow River

Christ the Savior Church. The original building was blown up on Stalin's orders, but a miscalculation of the amount of dynamite left a giant crater in the ground. This crater was made into a swimming pool, which lasted for about fifty years. Then at the end of the Soviet era, the swimming pool was re-transformed into a church.

Moscow State University, my mother's alma mater. Like the Moscow Metro, the scope of this place is mind boggling. Dorms, cafeterias, shops, sports facilities, concert halls, museums, professors' quarters, classrooms and labs are all in this one building. You could spend all your student days in here without ever having to leave, though the corridors with their sickly lighting would probably drive you to seek some sunshine.

There are many examples of interesting architecture in central Moscow, often in redesigned/renovated old buildings.

I have an idea for the Putin matryoshka: how about Medvedev nested inside Putin nested inside Medvedev....?!

Kolomenskoye estate, at the edge of Moscow. Beautiful grounds and woods, and food stalls that serve delicious blini with honey made from estate bees.

Cabbage is a popular Russian vegetable, good as a stuffing in pierozhki, as well as stewed, and in soups. Here's an ornamental patch at Kolomenskoye.

I saw many Russians, adults and children, make bouquets of these--big gold feather dusters carried one in each hand.

Tolstoy's house in Moscow, now a museum. It's a large house, with plenty of rooms (for his thirteen children) and many examples of fine weaving and embroidery by his wife, Sophia. I spent an afternoon there, with Olga. We got to hear a recording of Tolstoy playing the piano and telling a group of children to study well.

This statue of Pushkin on Moscow's Boulevard Ring is a popular meeting place. It's also one of many statues of writers around the city. I don't know if there's another city in the world that pays so much respect to its writers. An inspiration indeed!

Moscow, October 24

Exploring Moscow means seeing at every corner a strange conglomeration of past and present. A monastery from the 1500s abuts one of the Stalinist towers, whose ground floor is occupied by glitzy brands like Gucci and Piaget. At the entrances to Metro stations, babushkas—old ladies distinguished by their headscarves and flat shoes—sell flowers and pickled mushrooms to supplement their meager pensions, while immaculately groomed young women saunter by in mink stoles and leather boots. Such combinations of poverty and opulent wealth are very common, and they present a big contrast to Soviet times, when goods were very cheap but often in short supply. (In St. Petersburg, at the Marinski Theatre kiosk, my friend Nelli shook her head sadly. “In Soviet times,” she said, “we used to go every week to the ballet or the opera. Now tickets are so expensive only foreigners or the very rich can buy them.” Or BU students with Global Fellowships, I thought.)

In the center of Moscow, the most visible stores tend to be sickeningly expensive, and you can’t help but feel that the best commercial real estate has been handed over to foreign brands that all but a tiny minority of Russians find unaffordable. Here’s some evidence from the GUM, that light-filled, endless shopping arcade in Red Square:

...but it used to be a more bustling place with affordable, or as Russians say, "democratic" shops, as this photograph from the '50s suggests.

The good news is that there are places tucked away in corners that sell delicious food and other commodities for reasonable, or “democratic” prices. It helps to follow the crowds, and of course, have Muscovites for friends. Natasha took me to a market near her house where I found a fine pair of boots for about $50. And even on the top floor of the GUM, in an assuming buffet, I was able to have a hearty Russian lunch—fresh fruit juice, beet salad, mushroom soup, and blini—all for less than $10. And yesterday my mother’s former classmates Galya and Olga took me on the spur of the moment to a lovely Debussy concert at the Moscow Conservatory—where tickets were selling for $5. So I guess Soviet era-like prices have not disappeared completely. Nothing ever completely disappears in Moscow—as Donald Rayfield says in his introduction to Caroline Brooks’s work Moscow—A Cultural History: “…everything that ever happened to anyone, no matter how much the perpetrators would wish it obliterated, is somewhere recorded. Perhaps that is Moscow’s attraction (charm would be the wrong word): it is a city built on buried knowledge.”

Kazan, Oct 8-10

My last train trip from Moscow was to Kazan, the capital of the Republic of Tatarstan. It’s a very picturesque city, with a great many monuments. Russian and Tatar are both official languages here. Mosques and churches, often built side by side, are interspersed with high-rises. Currently Kazan is in the middle of a grand spruce up. The 2013 Universaide (a sporting event) will be held here, which, by the banners and advertisements I saw everywhere, is a big deal.

The Russian mathematician Nikolai Lobachevsky (1792-1856), whose work I became acquainted with when I taught high school math. He's known for his development of non-Euclidean geometry. He was a student at Kazan State University and later worked there, first as a professor and then as rector.

A room designed to feel like a cave, in a historic mansion that's now a public library. Not a bad spot to read!

October 7

I thought I’d ramble a bit about trains, having spent about fifty hours on them in the last month. Twenty-six of these hours were in a single stretch, from Novosibirsk in Siberia to Perm in the Urals. Enough time to let the wheels spin, so to speak. (Thoughts, and consequently language and metaphor grow lazy after a full morning and afternoon of staring at woods, fields, woods, fields–the pattern unbroken save for the rare dacha or disintegrating shed that flies by.)

Some basics about Russian trains: they run on time, they’re comfortable, and tickets can be difficult to purchase online. (I was spared having to do this by my father, who played the role of travel agent.)

I had decided to reread Anna Karenina while in Russia, and I got through two-thirds of it on the train before reaching Perm. I read it on my Kindle, where War and Peace resides as well. (Need I mention how, despite my love for real books—ink, paper, binding and all—I was glad not to have had to carry these two in my backpack?) Tolstoy’s depiction of the culture surrounding Russian train travel in the 1860s bears a quaint resemblance both to the contemporary scene and to my childhood memories of travelling by train in India. Platforms are bustling places: conductors guard the carriage doors and look stern and important in their uniforms; hawkers try to sell you food and magazines while porters and taxi drivers hover around. Families seeing off relatives climb into the carriages and sit with their loved ones until the train is ready to depart. (This last practice I find very endearing. Someone considerably older than I told me that it used to happen on planes too. It’s hard to imagine an era where people without boarding passes used to walk freely through airports, climb into aircrafts and sit with their departing friends or family until the pilot announced that the cabin doors were about to be closed!)

Once the train gets moving, it’s easy to get acquainted with the people in your compartment, just as Anna met Vronsky’s mother (and won her over, though not for long) on the ride from St. Petersburg to Moscow. My companion in Siberia was an elderly man named Vladimir. His English was about as good as my Russian, but within minutes we had established that I was a student and he was travelling to Ekaterinburg to visit his grandchildren. He dropped into my lap a handful of plums and tomatoes from his dacha, and only grudgingly accepted the sandwich I offered him in return. He showed me pictures of his grandchildren and seemed gratified by my smiles. Ochin krassivoy, I said, and meant it. All Russian children I’ve seen have been adorable and, compared to American kids, strikingly well behaved. They don’t throw food or temper tantrums at the table; in museums they’re quiet; and, like their parents, they’re usually very smartly dressed, in sturdy shoes, well-fitting coats, and brightly colored hats. Schoolgirls look very becoming with their swinging braids and ponytails adorned by ribbons or white gauzy bands.

Vladimir was fascinated by the Kindle, especially by how the font size can be adjusted. I imagine he’ll be getting one soon. In Soviet times, books were hard to come by, and it used to be a respected undertaking to acquire a full collection of an author’s work. Here’s one such relic from a restaurant I visited in Tomsk.

Balzac And finally, here’s one of my favorite passages from Anna Karenina. It captures, I think, not just the difficulties of reading on a train but the dual experience of reading a novel and existing in the real world.

At first her reading made no progress. The fuss and bustle were disturbing; then when the train had started, she could not help listening to the noises; then the snow beating on the left window and sticking to the pane, and the sight of the muffled conductor passing by, covered with snow on one side, and the conversations about the terrible snowstorm raging outside, distracted her attention. Further on, it was continually the same again and again: the same shaking and rattling, the same snow on the window, the same rapid transitions from steaming heat to cold, and back again to heat, the same passing glimpses of the same figures in the twilight, and the same voices, and Anna began to read and to understand what she read. Annushka was already dozing, the red bag on her lap clutched by her broad hands, in gloves, one of which was torn. Anna Arkadyevna read and understood; but it was distasteful to her to read, that is, to follow the reflection of other people’s lives. She had too great a desire to live herself.

Peterhof, Sep 28

Peterhof is a suburb of St. Petersburg, where Peter the Great built his summer palace. Its gardens, modelled after Versailles, stretch all the way to the Gulf of Finland. The place was designed to impress…and it certainly does, especially with the fountains, which are outrageously ornate. (The palace and grounds were ravaged by German troops after Peterhof was occupied in 1941. Restoration began after the end of the war, and construction projects in the gardens are still continuing.)

Sep 27

Despite the endless traffic jams and road constructions, St Petersburg exudes a tranquility that comes not just from the soft, ceaseless rain but from the city’s exacting design. Every block, every intersection and corner is composed to look like a postcard. Zoom out, and every bridge and lamppost fits into a larger plan. The Italian architects and designers hired by Peter the Great had Venice in mind when they devised this city. Its beauty comes in part from its unmistakable transposition from another place and time. Muted pastel buildings turn radiant against the grey waters, cobblestones and skies. Fairytale churches and halls rise from the canals like props on a grand stage. All ridiculously intricate and spectacular. And all precariously assembled on a bog floating in the Gulf of Finland.

Sep 22

I’m in St Petersburg and will be here till October 4. I want to get on to describing this breathtaking city, but before I do I feel compelled to say a little bit about my visits to Novosibirsk and Perm last week. Novosibirsk is not at all what I expected of a town in Siberia. It’s a big city, complete with malls, high rises, choked streets and flashing lights.

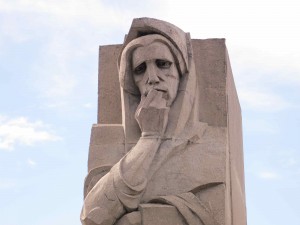

Below is one of several monuments in the center of the city to victims of the Second World War. More than 26 million people were killed in the Soviet Union during the Nazi invasion.

Many Russian apartment complexes, like this one, look like ghettos from the outside and even from the lobby areas. The state of the building is no indication of the state of the individual apartments--many are very comfortable, with modern furnishings.

Perm

From Novosibirsk I took a 25-odd hour train journey to Perm, a city of about a million people in the Urals. Located on the banks of the river Kama, Perm is a major hub of manufacturing and trade. It is also a cultural center. The Perm Ballet and Opera Theatre is well renowned, as is the Perm State Art Gallery, which is housed in this church:

I didn’t take pictures inside, but I very much enjoyed the collection of seventeenth-century wooden sculptures which included figures of Christian saints with very distinctive and often amusing facial expressions.

Here are some pictures of a reconstructed peasant village outside Perm. Many of the buildings have timber frames (i.e. no nails). Houses were often sectioned into two halves: a large winter room, built around the stove, and an unheated summer room.

Tomsk, Sep 8-9

Tomsk is one of the oldest cities in Siberia, founded over 400 years ago. Its population is around half a million, and it is home to many centers of higher education and scientific research. It really has the feel of a university town: libraries and leafy campuses, and young people everywhere. My hosts, the Panin family, have lived in Tomsk their entire lives. They gave me an enthusiastic tour; their pride and affection for their city were palpable.

My favorite statue. Chekhov, after a trip to Tomsk, called it a “dull town,” with dull people, an impression he formed from the “drunkards” and “intellectuals” he met during his stay. Here we have a satirical monument to Chekhov. The inscription on the pedestal says, “Chekhov in Tomsk through the eyes of a drunkard lying in a ditch who never read Kashtanka.”

Sights from around Altai:

Lunch at a restaurant in the small town of Artibash:

Climbing “Camel” Mountain

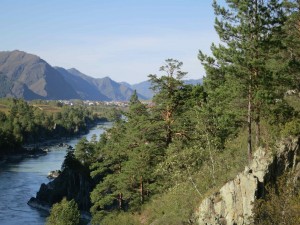

Altai Mountains, Siberia, September 10-14

These mountains span a region that overlaps Russia, China, Mongolia and Kazakhstan. The rivers Ob and Irtysh have their sources here. The name “Altai” means “Gold Mountain” in several languages.

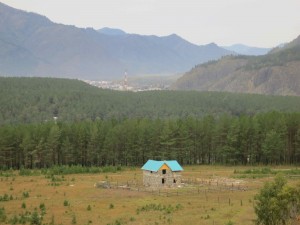

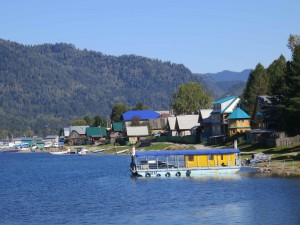

After a two-day visit to Tomsk (a charming city that I will describe later), I took a four-hour bus ride to Novosibirsk, the unofficial “capital” of Siberia. It’s a city of about 1.5 million people (the third most populous after Moscow and St. Petersburg), located in southwestern Siberia, on the banks of the Ob. It took about eight hours by car to drive from here to the Altai region. We (my host Evgeny, his colleagues Vladimir and Boris, Boris’s daughter, Lena, and I) spent two nights at Lake Teletskoye, and two nights near the village Chimal, where we climbed “Camel” mountain (верблюд). The weather was lovely the entire time. I was surprised by how warm it was—while Moscow last week felt like Boston in November, the daytime temperatures in Siberia stayed well above seventy degrees.

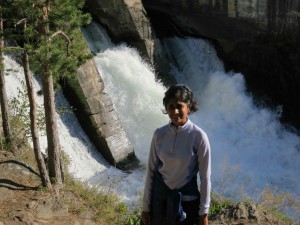

Lake Teletskoye is about 50 miles long and 3 miles wide. The water is very clear (and cold). We took a motorboat tour of some of the waterfalls in the surrounding hills.

a hydroelectric station at one of the waterfalls

a hydroelectric station at one of the waterfallsMoscow, September 7

I landed in Moscow two days ago but won’t really have a chance to explore the city until I return from side trips to Siberia and St Petersburg. My hosts Ram and Natasha live very close to the center of the city, near the Metro station Taganskaya. It’s an old residential neighborhood, with many houses from the 1800s preserved as monuments. The pictures here are from short walks I took with Ram and Natasha. Tonight I take a red-eye flight to Tomsk.

Wild City Mushrooms

Natasha made a sumptuous mushroom soup yesterday. Clear broth, fresh dill, and large jelly-like slices of mushroom that slipped out from under the edge of my spoon whenever I tried to cut them in half. She had found them growing near her dacha in the outskirts of the city. “This big,” she said, and held apart her hands as if she were describing a medium-sized rabbit.

“Are there poisonous mushrooms in Russia?” I asked.

“Yes,” she said mildly. “But not this one.”

Russian children, I’ve been told, are taught early on to spot and identify wild mushrooms, which are a free source of nutrition and flavor. Ram, who has lived in Russia now for more than thirty years, has evidently picked up the skills: on our way back from the market today, he noticed a spread of champignons in a grassy patch of black soil, right by the main road, which was clogged with traffic. Round, white caps poking out of the ground, each topped with a little pile of dirt, as if the mushroom were about to shake itself clean. The black soil, Ram said as we picked the patch clean, had been carted in during the spring from the countryside and was rich with spores. Ten minutes later we came upon another grassy patch near Ram and Natasha’s apartment. This one was dotted with a brown variety that’s supposed to be good for frying. We got home with enough mushrooms from to cover the entire kitchen table.

I was reminded of how last summer in Maine, my husband and I came upon some cone-shaped mushrooms in the backyard. We identified them (by comparing them to a diagram in a mycologist’s guide) as parasols, edible. They had the white and brown patches and the distinctive rings on the stems. Still, we were hesitant to cook them. My husband’s relative had once poisoned her dinner guests by serving them mushrooms she’d picked in the same backyard and mistakenly identified as edible morels. “How do we know for sure,” my husband asked, “that they’re not amanitas?”

We didn’t, and that’s why—even after we had sautéed the caps in butter and agreed that they smelled too good to do any harm—our appreciation for their delicate flavor was clouded by phantom sensations of nausea. But Natasha’s soup I didn’t question for a moment and enjoyed to the very last drop of my second helping.

June 8, 2012

I’m headed to Russia, to visit Moscow and St Petersburg. My parents spent several years in the former Soviet Union, as students, and I’m excited to have this opportunity to see some of the places they experienced in the seventies. Undoubtedly Russia has changed since then. I look forward to exploring these important cities and to meeting new people, including some of my parents’ friends from college whom I’ve never seen before.