For a couple of decades now, people have been debating over the benefits and costs of wind turbines and wind as a renewable energy resource. Specifically there have been debates of the pros and cons of using offshore wind for energy. Many of the same arguments for and against onshore wind farms are used in the debates for or against offshore wind farms. However, there are also more topics to discuss when it comes to offshore wind farming, making the debates larger and the policies needed to create offshore wind farms more stringent.

Denmark was the first country to create an offshore wind farm and proved that there are many profits that go along with using offshore wind energy. Though there are undoubtedly disadvantages, certain states in America are trying to take steps in the same direction. Lobbyists, skeptics and budgets are delaying their progression, especially in New Jersey. Despite the fact that offshore wind farm development in New Jersey is slow moving, and will continue to be so, it should continue even if incentives must be put in place.

Using wind as a renewable energy resource is a slow moving process mostly because of certain costs and risk factors. Onshore wind farms are easier to build because of their location. Moving equipment on land is easier and less costly than moving it off land. Further, workers need to be able to put the turbines together. Much of this process can be done on land, but some of this work must be conducted on location. With such a location as a few miles offshore, stability, travel and efficiency becomes increasingly harder than onshore. Additionally, “Offshore work involves increased risks of storms which affect the amount of time available for maintenance and installation which in turn influence capital and operation costs” (1). Along with constructional difficulties, come maintenance difficulties. Because much of the turbine is underwater and open to harsher condition, the materials are more apt to corrode or deteriorate. To counteract this problem, people will constantly need to fix these issues or spend more money on better materials that can withstand such condition. (1) All of these problems factor directly into a higher budget for offshore wind energy than onshore. Many lobbyists and skeptics who are against wind farm development use these complications as reasons to not move forward, and try to get the state to agree. Though the state, for the most part, endorses wind farm development, these peoples’ arguments and views are not ignored. They create friction and hinder the progress.

Offshore wind farm development takes a long time on its own, even aside from conflict with lobbyists and a budget. For example, in December 2008, Bluewater Wind Energy Company received a budget of four million dollars from New Jersey to develop an offshore wind turbine, the first in the nation. However, due to tests for wind data collection that needed to be done and other set backs, much time went by without signs of development. After three years, the state decided that the time gone by was time wasted and revoked the money from the company. (4)

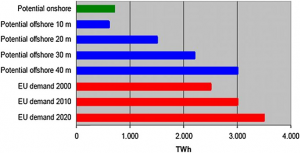

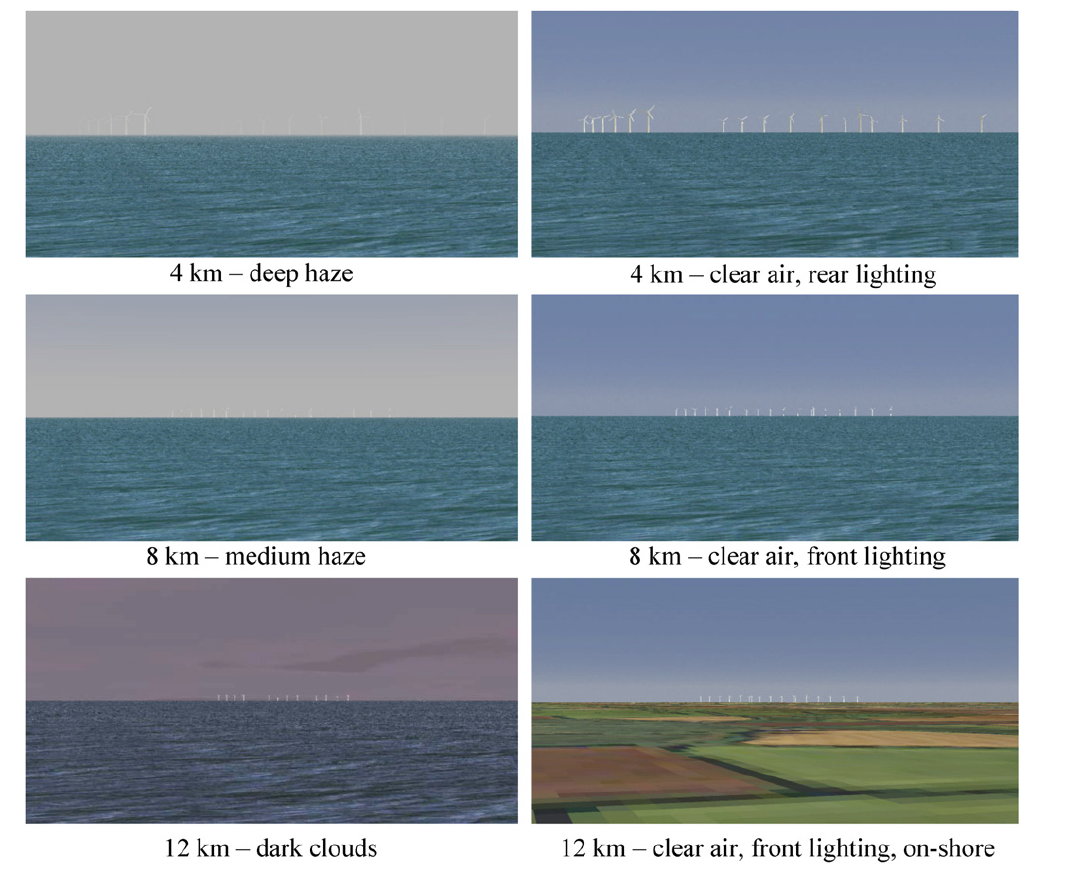

These conflicts, while they are setbacks, should not be reasons to end advances. Some of the many reasons to continue trying to build offshore wind farms are the same reasons we build onshore wind farms: wind farms increase air quality, reduce foreign fuel dependency, mitigate climate change and create jobs. Further, there are many complaints about onshore wind farms are not problems for offshore wind farms. For example, since the turbines offshore will be farther from people, there will be fewer problems with flicker and noise. It can even be seen that offshore wind turbines will create more energy for use because the winds offshore are higher than the winds on land. (1) These advantages are simply taken from comparing and contrasting different farms and energy sources at face value. If a deeper look is taken into the benefits of offshore wind, specifically in New Jersey, more rewards come to light.

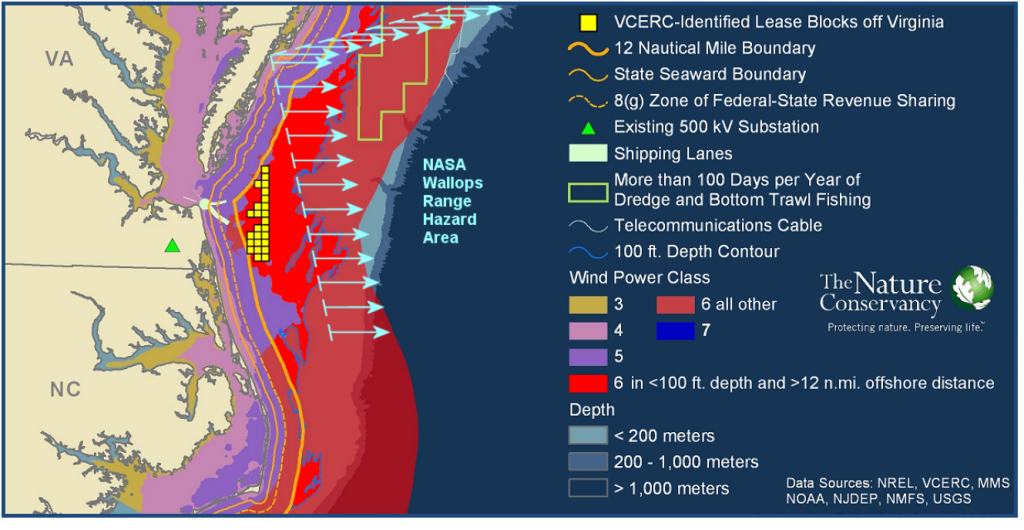

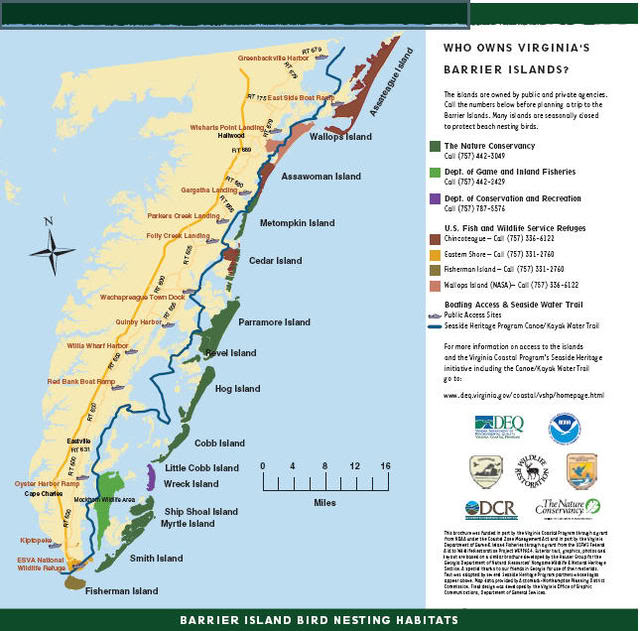

New Jersey especially should invest more research, money and time into the offshore wind development. The lower half of New Jersey, from about Monmouth county and down the coast, has powerful offshore winds. Specifically around Cape Cod, wind turbines would be very effective because of the shear amount of wind they could convert to usable energy. In terms of offshore wind power, New Jersey is one of the states with the most. Along with Massachusetts, Rhode Island, California and Hawaii, New Jersey’s offshore wind energy potential is of the greatest in the nation. (7) If New Jersey were to become the first in the nation to develop an offshore wind farm, the benefits would be great. (5) Further, if New Jersey were to create more wind turbines, the “offshore wind would produce approximately 3,000 MWh/yr for each installed…Power densities of approximately 20 MW per square mile could be harvested while occupying less than .01% of the seabed within a project area” (3). The significant contributions to New Jersey’s renewable energy profile is reason enough to increase the number of wind farms, offshore wind farms especially, and continue progress in development.

The benefits of offshore wind should fuel investors into providing support but it does not. In 2011, “NRG Bluewater Wind, announced that it would back out of a three-year-old power-purchase agreement with Delmarva Power because it couldn’t generate sufficient investor interest” (6). If more investors understood the advantages of offshore wind farms, less pressure would be put on the government to back the movement and it would probably go faster. Along with the already apparent profits of wind farm development, incentives should be put in place to make investors realize the immediate payback of their investment.

Market-based incentives are already present without the help of political action. For example, the price of natural gas, a major current energy source, is very unstable. Wind energy however, has become more stable and has decreased due to more efficient turbines that have been built. The United States government, or even just state governments, can look to other countries to find incentive ideas that work. The federal government can administer a credit applied per kWh to the output of facilities. This credit does not need to last forever, even just implementing it for the first five or ten years could help to offset the cost of building offshore wind farms. Further, state governments can construct tax plans or other financial incentives just as the federal government can. The consumers can even make a difference by voluntarily purchasing green energy. This will drive demand up and investors will realize that supplying cleaner energy is worth the cost. (2)

New Jersey has tried to create new incentives, but other state government departments have shied away. While you would lose money immediately on the investment, the money gained from taxes would surpass that budget. Additionally, New Jersey has adopted lucrative incentives to lure firms to New Jersey from other sites. (8) Such practices should continue. New Jersey has such a high supply of wind, especially offshore. The benefits of converting it to usable forms of energy greatly outweigh the costs. Incentives, put in place by the government or consumers through the market, would help to offset building and maintenance costs, one of the major disadvantages of offshore wind farms. The movement of developing offshore wind farms has to start somewhere. Why not in New Jersey?

- Snyder, Brian, and Mark J. Kaiser. “Ecological and Economic Cost-benefit Analysis of Offshore Wind Energy.” ScienceDirect.com. Science Direct, June 2009. Web. 28 Nov. 2012. <http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0960148108004217>.

- Lori Bird. “Policies and Market Factors Driving Wind Power Development in the United States.” ScienceDirect.com. Science Direct, July 2005. Web. 24 Nov. 2012. <http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0301421503003835>.

- “New Jersey Offshore Wind Energy: Feasibility Study.” New Jersey Clean Energy. Atlantic Renewable Energy Coorporation, Nov. 2004. Web. Nov. 2005. <http://www.njcleanenergy.com/files/file/FinalNewJersey.pdf>.

- Caroom, Eliot. “New Jersey.” The Star-Ledger. N.p., 09 Oct. 2012. Web. 24 Nov. 2012. <http://www.nj.com/business/index.ssf/2012/10/offshore_wind_farm_plans_for_n.html>.

- Miller, Michael. “New Jersey Losing Ground in Race for First Offshore Wind Farm.” PressofAtlanticCity.com. N.p., 30 Mar. 2012. Web. 24 Nov. 2012. <http://www.pressofatlanticcity.com/communities/lower_capemay/new-jersey-losing-ground-in-race-for-first-offshore-wind/article_43e71bb2-7a04-11e1-bcad-0019bb2963f4.html>.

- Caperton, Richard. “Congress Needs To Push Targeted Incentives For Offshore Wind.” ThinkProgress RSS. N.p., 13 Jan. 2012. Web. 24 Nov. 2012. <http://thinkprogress.org/climate/2012/01/13/403620/congress-incentives-offshore-wind/?mobile=nc>.

- “U.S. Energy Information Administration – EIA – Independent Statistics and Analysis.” DOE Provides Detailed Offshore Wind Resource Maps. N.p., 30 Jan. 2012. Web. 24 Nov. 2012. <http://www.eia.gov/todayinenergy/detail.cfm?id=4770>.

Johnson, Tom. “Lawmakers Propose Another Tax Break for Offshore WindNew Bill Would Exempt Wind Manufacturers from Paying Sales Tax on Materials and Equipment.” RSS. N.p., 24 Sept. 2012. Web. 03 Dec. 2012. <http://www.njspotlight.com/stories/12/09/24/-another-tax-break-for-offshore-wind/>.