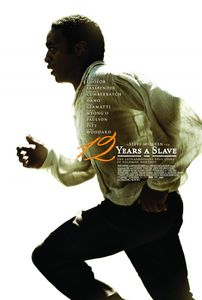

12 Years a Slave is a beautiful, horrifying, and challenging film. It is the story of the capture and enslavement of Solomon Northup, a free black man from New York, after he is duped into taking his violin performances dangerously close to the border and slave states on a promising concert tour. He quickly finds himself in chains, and then in Louisiana, no longer his own master. For the next twelve years, he is passed from plantation to plantation, finding ways to survive amongst unspeakable suffering. Forced to keep his past unspoken, his ability to read and write hidden, and his passions in check, Northup is nevertheless determined to make the best of his situation, biding his time while he keeps the hope alive that he will one day return to his family.

12 Years a Slave is a beautiful, horrifying, and challenging film. It is the story of the capture and enslavement of Solomon Northup, a free black man from New York, after he is duped into taking his violin performances dangerously close to the border and slave states on a promising concert tour. He quickly finds himself in chains, and then in Louisiana, no longer his own master. For the next twelve years, he is passed from plantation to plantation, finding ways to survive amongst unspeakable suffering. Forced to keep his past unspoken, his ability to read and write hidden, and his passions in check, Northup is nevertheless determined to make the best of his situation, biding his time while he keeps the hope alive that he will one day return to his family.

I spoke with the screenwriter John Ridley, who adapted Northup’s memoir on spec, hoping that his project with director Steve McQueen would be produced if he could make it good enough. When I first got on the phone with Ridley, I told him that while I did not enjoy the film, per se, he had certainly accomplished that goal. Northup’s journey is a tear inducing, harrowing experience to watch. Over a century of American film has not been able to produce such a powerful depiction of the peculiar institution. Our conversation touched on everything from the religious lives of slaves to Hollywood’s failure to provide us with sufficient images of the era.

-Rob Ribera

How did you first get involved with this project, and what were your first impressions of the source material?

I had met Steve McQueen, the director, in about 2008, and we talked back and forth about various subject matter and landed on the concept of really examining this time period in American history that we thought had not been excavated and fully rendered in every respect—the difficult parts, the beautiful parts, the human parts. We’d gone back and forth on material and finally landed on the memoir 12 Years a Slave, and when I read it I was just astounded by many things. I had never heard of the story, I was not familiar with it. And the way it was written, the specificity of detail, the elevated language, how evocative it was, what an amazing diary it was of one person’s twelve year long saga. And it really seemed like it was, just in that first reading, that it was a perfect piece of material, that it could lend itself to rendering many aspects of American history and the slave institution that people were not familiar with. That was the jumping off point.

How did you work with Steve McQueen as the screenplay came together?

Well that was only in that Steve lives in Amsterdam and I live in Los Angeles and during that—you know it was about a four year long process. And within that space he went off and made his second film, Shame. So a lot was just early conversation, was just going through the book. It was a unique situation in that it was a spec script. This was not something I was paid to develop. Normally, to take a studio situation, you are paid to develop something, and there’s a lot of conversation. This was more of, “Can I go off and write a script and make something that was impactful that people would want to then attach themselves to it—the actors, other individuals?” So it was a unique process in that it was more solitary some in ways than some of the writing projects I’d been involved in before. There were some things that were really good about that. I think it is a better script because I was able to not have to worry necessarily about fulfilling studio requirements and making it a little bit more upbeat in places or less extreme in some places. I could concentrate more on really translating that source material and those powerful feelings, that emotional velocity that I felt when I first read it, really putting those on the page. And I think being in a more solitary place allowed me to really translate that material in a much, much better way.

Knowing that you were going to be making this film with McQueen, did you tailor some of your writing to his sensibilities?

We certainly had conversations, but the thing you have to remember is that at that point, it wasn’t that long ago that we started doing this, but Steve had only one film that was finished, so I had seen it and thought it was an absolutely remarkable film but the wider world was not the Steve that people think of today. His language of cinema was not as clearly rendered as it certainly is now, so in the writing it was a lot of individual thought in what simply makes the best story, what is the best way to translate Solomon’s memoir onto the page and then build that out for the screen? We had many conversations, but because it was a spec script, again because of the distance and because he was working, it was a situation more where, for me, it was finding the absolute best story and having the belief that others could come in and help elevate it off the page, which they certainly have.

When writing a project like this do you feel an obligation to history, and how do you balance that with an obligation to the drama and the structure of a film?

That’s a really good question. That’s a really, really good question. Over the last few years I’ve done a good number of historical projects, including Red Tails, a screenplay at Universal about the L.A. riots, this film, and a film I just wrote and directed about Jimi Hendrix. We are certainly in an era where people are more sensitive to history. It’s easier for them to find history, to go on the Internet and look things up. And I also think that there’s more of an industry that’s grown up about really being picayune about the films. Whether it’s this film or Zero Dark Thirty, or Argo, or what have you, where people just go, “Well this didn’t happen and that didn’t happen.” On one level it’s a bit aggravating in the sense that oftentimes, like with 12 Years a Slave, you are bringing history that most people did not know about—and I put myself at the top of that list—I’m no more savvier in that regard than anyone else. When you present them with history you need to do it in a cinematic way. Just from the jump, you are taking twelve years and reducing it to two hours and fifteen minutes, so there is a level of duplicity in a sense there, where we’re telling you at the jump that we can’t put everything in this film.

So with people who have a subject matter that they’re not aware of and they get picayune about it, it’s a little annoying. But at the same time, I do think as a writer, particularly when you’re dealing with an individual who endured so much to tell this story, then yes, there’s an obligation to try and be as faithful as possible to the facts of the story, and certainly the emotional honesty of the story. That was a balance that I was working with and I think most writers in a situation like this are working with. You’ve got to entertain people, and as you said with this movie it’s not in a strictly thematic sense entertaining, but it enthralls. And to do that you have to remain true to the source material. But within that as well, you’ve got to make sure you’re presenting something that is cinematic and really moves folks along.

There has been some discussion about the fact that the film was produced, mostly, by non-American filmmakers. There are two aspects to this criticism—one is about artistic territory, so to speak, but the other is about the failure of, or the reluctance on the part of American filmmakers to tackle the subject. What do you think about that kind of commentary?

To be honest with you, I think, first of all, Solomon Northup is an American. I think he is the individual most responsible for the story at all. The fact is he left behind a document that is so vivid, so evocative, so emotional, and speaks to the right of self-determination, which in and of itself is not a right that is limited by any means to Americans. The American would say we do it better than other people, but it is something that anyone at any place at any time can relate to. Within that, I’m an American. So the concept that you can have an American book—the American book on slavery as far as I’m concerned—and an American writer and nobody else from some other background should be allowed to work on or could understand the subject matter—that criticism I don’t quite get.

Certainly we want to educate the American audience, but again, the right to self-determination, freedom, liberty, those are things that everyone in the world should relate to and stories that should be told. Whether it’s South Africa, Syria, or in the Middle East, Eastern Europe, these individuals have been through this as well. I find it—and I know you are asking the question, you’re not pointing any fingers—but it’s kind of a nit-picky thing, especially when you consider we as Americans constantly find stories from around the world. Nobody in America complains because we have this worldview that we feel allows us to speak to the world. Knowing that this is an American story literally, and who wrote it originally, and knowing my own involvement—the fact that anyone is upset, I’m not sure why they left it around for someone from another country to tell the story. This story has been around for 160 years, so people in American have had ample opportunity to find it, excavate it, lift it up, film it, to tell it. And if you have folks from other countries who are going through the dustbin of American history and finding something of value of holding it up for us and saying, “Why aren’t you folks paying attention to it?” We’re certainly in no position to be upset at them at that point.

What was Henry Louis Gates Jr.’s role on the film and how did you conduct your own research? There are a few of these narratives, of free men who were captured, and obviously Frederick Douglass’ own narrative stands out from the period. So did you look into those and find other sources that helped you along with your own writing?

Professor Gates was immensely helpful, and I think more so directly with Steve. There were many things that I found and researched and just looked through, some for what went into the screenplay itself and others just for my own education. There was a learning curve. You’re American, you’re African American, and I think there are some assumptions about what you know about slavery. In just the early cursory study I realized I know nothing. That was an education. I think with Professor Gates it was about building on the page with Steve and looking at what was there and all the information that I had given. And for me it was a big thing—in writing the script it wasn’t just about the words on the page. There’s that. There is the dialogue; there are those fundamental elements of screenwriting. But with something like this I really wanted to try to build out a bible. Not knowing the level of awareness that anyone would come to with this story, about American history in general, about slavery, I wanted to add as much detail as possible to the script so that people would have a jumping off point, they would have something they could build off of. Maybe things they may never need or use, but at least have some kind of reference coming in, because making a film it’s a very quick startup and you never know when people are going to come into it, how much time they are going to have to research it, and just their own levels of awareness.

So within that, once that script was in Steve’s hands, he and the professor worked hard to bring Steve up to speed about some elements of American history, about slavery, and he was available to anyone who needed, that his infinite knowledge in that subject matter, as reference. For me, I would say, the books that I looked at, I looked at some slave narratives, but I really wanted to learn as much and many different things about American slavery, about the history of it, about it’s inception, about its transformation here in America, about events like the Stono rebellion, or New York Burning. This exhaustive piece that PBS had done a few years back, Africans in America, that had both been written up as a source book as well as a multi-part documentary that really was one of the best collections on the history of slavery, slave narratives, even narratives by plantation owners and abolitionists. A very rich volume, that again, most people were not familiar with. So in the early stages it was really getting a fundamental education, learning as much as I could, reading Solomon’s memoir, trying to create context for as many things as possible. And then, within that as well, writing the script. There’s still that—writing the script. There’s a reason it was a four-year-long process, but I would say it was one of the most enriching experiences I’ve ever had as a writer. Ultimately, as difficult, as painful as some of it was, it was easily one of the most rewarding experiences I’ve had as a writer.

Solomon’s religious journey is complicated, to say the least, and not unlike that of many slaves. The presentation of religion in the film certainly expresses some of those complex issues. I’m thinking of two scenes in particular—that of Epps’ speech about the blessings of God, Patsey, and righteous living, and of Solomon joining in the singing of Roll Jordan Roll. We see religion as corruption and redemption.

Solomon’s religious journey is complicated, to say the least, and not unlike that of many slaves. The presentation of religion in the film certainly expresses some of those complex issues. I’m thinking of two scenes in particular—that of Epps’ speech about the blessings of God, Patsey, and righteous living, and of Solomon joining in the singing of Roll Jordan Roll. We see religion as corruption and redemption.

The interesting thing in reading a lot of the history you realize how much more religion was a part of the fabric of American life than it is now. As much as we talk about religion and faith every election cycle, the question about faith-based voting and things like that, it was just such a hard and fast element of American life back then. And certainly then, as now, people used either religion or their interpretation of religion to their own ends. Within Solomon’s memoir it is a heavy thread, not just merely individuals preaching their philosophy of what the bible is about or what God’s word is, but even elements of masters giving their slaves bibles and whether it’s appropriate for a slave to read at all, which certainly many people felt it wasn’t. And if they are going to be allowed to be able to read the word of God, or whether or not the word of god should be preached, which I think is very interesting, this concept not just withholding reading from individuals but saying you can’t discover God in your own way. You can be taught it but you can’t discover it in your own way because you may take a different feeling out of it. So there were elements that I wanted to definitely keep in the screenplay without preaching too much, no pun intended, about how religion was used in that time period to either enlighten or subjugate individuals, to simply put in context that it was used in some way shape or form.

And at the end, with Roll Jordan Roll it is a building on that. In its rendering in the film itself is an amazingly powerful moment, which is so much on Chewitel’s performance of an individual who, for me, what was very interesting about Solomon, was someone who was very intellectualized, very much someone who was living in their mind, very much an individual who tried to compartmentalize a lot of the aspects of what was happening to them, about having a faith in the systemic value of the system that somebody will free him. Or with Eliza if her children are being taken away, you don’t cry for them outwardly, arriving at a moment where he can no longer contain his emotions and they can flow freely. And I hope and I believe that audiences will understand the truth in that. Things like spirituals which have become a stereotype of people of color or black churches, but people realize where this came from, that it’s not just something people of color do. That was their hope and their drive and their salvation for hundreds of years, and why those things remain close to the black community is because of how it uplifted the black community. So within this beautiful, beautiful moment within this film, in these twelve years, in this progression of Solomon, I would hope the audience sees the progression of black culture, why these things are important to us, where they came from, what they mean. They’re things that, as with any culture, that we hold true are not to be dispensed, they are things to be understood.

Some feel that slavery, perhaps like the holocaust, is almost an untouchable subject because it presents a problematic, lose/lose situation where you have to depict pain and suffering but you don’t want it to seem like exploitation. How do you respond to that, and how do you find the balance?

The opposite of that is to not depict it at all, and I think that Hollywood has done a pretty good job of not depicting it at all over the last 85-100 years of filmmaking. History in general is not something we should shy away from. It’s a truth. It’s a reality. And it’s there, and again, I include myself. There are many aspects of history, not just this, but year in and year out films come out within things that we don’t know anything about. These films are not meant to be 100% literal or documentaries, but to say look, here’s something that happened in history that you should be aware of and we hope that we’ve energized you enough to go off and learn more, to research on your own, to just find out. So the concept that we should not, and I’m going to limit my perspective to this film, that we should not try to restore Solomon’s story to a rightful place of prominence, that we should not try in any way shape or form try to render what slavery was or its brutality but equally its humanity.

Again, to your previous question about the Roll Jordan Roll moment, in my opinion it’s certainly one of the most beautiful moments in film that I have ever been a part of. To see a moment like the slave Patsey who is making these little cornhusk dolls of a family and thinking about the family that she could have. To say that we shouldn’t do one is to say that we can’t do the other. To not be able to see the enduring spirit of people of color, of individuals who were enslaved, who never gave up their faith in the system, in each other, for a better life or in their country, I think is wholly wrong. And I think that there are some people today who would like us to not talk about these kinds of things, but unless all of us—and I mean black, white, whatever—unless we are educated about this system, about where we came from, about how we all were given over to this mass hysterical belief that racial inferiority was and should be the norm, and should be canonized into law, unless we really get past that, you look at where we are in 2013 and how far this country has come but how we’re still so calcified in regards to some feelings about race, this is why. It’s because we don’t represent these things, we don’t talk about these things, we don’t educate ourselves. And we don’t see the humanity in each other. I think this is a film that does that. Regardless of the subject matter, I think we need these kinds of films from time to time.

How did you find the structure of the film? How does it compare to the book, and how do you find the balance between what very well could have been two hours of horror? Of trying to condense twelve years of the experience of a slave into what could have been four, five, six hours of beatings and horrible experiences.

A lot of that I would really point back to the memoir and what Solomon wrote. And the reason that I think it was not two straight hours or had it been six hours of just straight beatings and torture is that it goes to Solomon’s character. This was a man of incredible will and incredible fortitude, and an individual who was able to find much beauty around him even in the most horrific of situations. The way that he treated other people, the way he would defend people who were weaker than him. The way that he would create beauty through his music, through his intellect in moments, for example, where he’s building the raft for master Ford, saying, “I’m not merely going to spend the next however many years a victim of circumstance, but offer myself up when I can.”

Those are the things in my opinion elevate his story from being merely exploitational, that it really is a story about the human spirit, and a story about that spirit personified in an individual who would carry on despite all of the things that were going on around him because he did have faith, and he did have a belief that he could endure, that eventually he would find those individuals who could vouch for him and return him to his freedom. I think that element of that story, although the perspective may be slightly different than other narratives at that time period is a theme that you would find running through most of the lives of these individuals, of slaves, who just would not give up, and would either survive on a fundamental day by day basis, or give themselves over to the fight for civil rights. When you have stories like that, it’s not going to be monotonous, it’s not going to be one-note, and it’s not going to be depressing. Solomon was not that character, he was a spirit who enlifted, and I believe that in the telling that’s what people walk away with, an elevated and enlifted spirit.

I found it fascinating that you begin the film with this juxtaposition of women, intimacy, and time. And as an extension of your thoughts on historical accuracy, the scene with Solomon helping to bring the woman to sexual satisfaction is not strictly an historical moment lifted from the memoir, but does bring up another point about sexuality in the lives of slaves. Why begin this way?

What we wanted to happen there was that concept of a desperate sense to feel alive, and to feel like a person, and you can split that off into a man or a woman, of having some kind of contact in any shape or form that does not end with a fist or a whip. And also that moment directly afterwards where you realize, this is not my loved one, this is not a moment that is truly tender or is about emotion. Within the slave system it is so difficult to find a moment that matters in life, when everything has been stripped away from you. And that continues throughout the film. When Patsey’s only family is the only cornhusks she makes, when Eliza is stripped away from her family, or Solomon is not able to write to his family at all, or Patsey who wants just a little bit of soap to smelly nicely. Slaves don’t even own their sleep patterns when they are woken up in the middle of the night for the entertainment of others.

So for us, it was taking a moment, and saying, what is one of the most fundamental things that an adult man, an adult woman wants? You want contact. You want to know you matter. You want to know at the end of the day that someone cares about you. That’s the reason people go home at night. You’re working all day, it’s been a crappy day, but you go home and your kids are there, your wife is there. Sometimes even that is crappy, but when you fold up in bed at night you say this is what I’m working for, these people care about me. Once you rob them of that, to even have the attempt of human contact. That was just a different way to start the story, a different way into the story to make the audience know that this is a story that is about the search for value on the most fundamental level, not just in the big scope of one day I can be free, but that one day I can matter again.

Speaking of the role of women in the film, you do give them a strong voice here as well, Alfre Woodard’s role as Mistress Shaw, who gives voice to another path to survival or Sarah Paulson’s role as Mistress Epps who has her jealousy come to define her, and of course Lupita Nyong’o’s difficult role as Patsey, present different glimpses into the lives of women at this time. We’ve been talking about the roles of people of color in the film, but can you talk about writing these complex parts for women at a time when they too are under-represented?

Speaking of the role of women in the film, you do give them a strong voice here as well, Alfre Woodard’s role as Mistress Shaw, who gives voice to another path to survival or Sarah Paulson’s role as Mistress Epps who has her jealousy come to define her, and of course Lupita Nyong’o’s difficult role as Patsey, present different glimpses into the lives of women at this time. We’ve been talking about the roles of people of color in the film, but can you talk about writing these complex parts for women at a time when they too are under-represented?

Well in general, it’s unfortunate, the fact that women outnumber men certainly as film goers and ticket buyers, but they tend to not get films that have strong female characters at the center of it. Part of that is the number of women behind the scenes, the decision makers. When anyone questions why there aren’t more Asians or Hispanics generally you can find the answer if you look behind the camera or in the executive office. That will answer your question. There certainly are a good number of women who are decision makers, but it’s unfortunate that you see particularly women over the age of forty start having a very difficult time finding substantial roles. And then it tends to be the same actresses over and over again who are getting those roles, which is great for them, and they should. But you’re not getting wider body of representation of females.

For me, writing characters that are complex, I wanted all the characters, even once that may have been repugnant, to at least be complex. You’d never forgive them or forgive what they did or how they behaved, but that there was a complex nature to them. For example, sticking to Mistress Epps and Mistress Shaw. Mistress Shaw, even though she was a woman of color, she was gaming the system a little bit. She certainly had to have any measure of freedom, but I didn’t want to write her as a pure angel but rather a woman who said, “I’m not going to be a victim anymore, what am I going to do to get out of it?” And equally with Mistress Epps, who was very much a racist, but you could see that she was on the receiving end of bad things as well. There was a certain cycle of violence that she was caught up in. I think people appreciate complex characters. One-note characters, it doesn’t matter if it’s this or a comedy: one note becomes one note. It’s very easy to get bored with it. Were they a little more difficult in this circumstance because one note that I could not play was sympathy with a lot of these characters. But again, within that source material, what Solomon wrote, he did such an amazing job of reportage detailing his details of characters. He made it fairly easy to help create fully formed characters on the page.

There is a powerful line, one of many in the book, that Solomon writes right after he is forced to whip Patsey and Epps then takes the whip himself. Solomon writes this about Epps’ face: “The tempestuous emotions that were raging there were little in harmony with the calm and beauty of the day.” When I read that, I couldn’t help but think not only of Solomon’s experience and still being able to appreciate the beauty around him, but it also made me think of the film, with all the shots of nature, almost like a hint of Malick’s work, where we are looking up at the trees and the sky. Were those moments of relief in the screenplay? Also, a parallel would be, the opening shot is a good example of these tableaus, almost like paintings of people standing, looking, and waiting.

There were elements certainly from the book in Solomon’s descriptions of the geography and the landscape that I absolutely wanted to transfer over, but I think that’s a huge element of not just the general geography but the nature of that time was a little more raw and looked a little different, and I wanted to represent that. Certainly different than Saratoga where Solomon lived in the north, and trying to separate those two places as much as possible.

I have to give much compliment and much admiration to the cinematographer Sean Bobbitt, who I’ve gotten to know over the course of putting together this film. Those images that you see, the color palettes, the framing, that’s Sean, and he is an amazing cinematographer, a really fantastic person. I think it’s a terrific script, but ultimately the words on the page are just a part of it, and there’s so much of the film itself coming alive through the cinematography and the person who does the camerawork, and what Sean did in this film was to take what was on Solomon’s page and translate those moments like you just read where there was just a harshness to what is happening to these individuals but the environment around Solomon is just starkly beautiful. It is a hard kind of beauty, and it takes a very talented individual to be able to match those two things in a real space, and I honestly can’t say enough about Sean Bobbitt, about his work and his approach, and his ability to capture all that.

There is a long shot later on in the film, after Solomon has spoken with Bass about writing the letter, where we see him stare off screen for a long while and then, uncomfortably right at us. Can you talk a bit about this moment of breaking the fourth wall, this challenging moment for the audience? Was that in the script or not, and how do you feel about this film as a conversation starter, as a challenge?

It certainly is a challenging film. As you said when we first jumped on the phone, you can’t really say that you enjoyed the film. I’d never say to anyone that they have to go out and see the film, but once it is seen it is not easily forgotten. And I think that is an essential part of creating something whether it is a film that is meant to be highbrow or whether it is a film like Inception, for me where, I can get all of it, but it begs to be fully watched. I think that’s very essential and very important. I would say, with creating a film, you have to try and use as much of the language of cinema as possible, without using tricks, without using it in ways to fool the audience. Do the words on the page work? Is the sound editing there? Is the score there? Are the performances there? Is the framing there? Does it work on multiple levels? And I believe this film does.

In terms of being a conversation starter: the conversation to me that is most important out of this film is people talking about Solomon, his story and his journey, and really making his memoir a part of our cultural landscape again. This was, in its time, a very important and a very prominent book, and it has just completely fallen away from our psyche. As someone who is part of this film I’m incredibly thankful and appreciative that people are discussing it in any way shape or form, especially if it is not in a bad way. But at the same time, what Solomon had to go through to deliver this story to us, to all of us, is fairly phenomenal. And if people are, from now forward, putting this book into part of their conversation about our history, then I think that’s in and of itself is a pretty special accomplishment.

Django Unchained certainly had its own approach to the time period and brought up its own issues of historical accuracy and exploitation. Lincoln had some criticism leveled at it for mostly scrubbing out the African American side of the story. Are there some films that you think bring justice to the material more than others?

In terms of what other directors or artists choose to leave in or take out or how they want to handle the story or not—that’s their business and their decisions. I didn’t see Django, not because I didn’t want to see it, and not because I didn’t want to feel like I was competing with it, it’s just not the kind of film I want to see. I didn’t see Inglourious Basterds either. I’m sure it’s a great film, an entertaining film, it’s just not particularly the kind of film I want to see. Lincoln I did see, and I think it’s a phenomenal film, and I get where people might say, oh you’ve kept slavery at an arms length, but to a degree I think that was part of the issue of bureaucracy. For a lot of those folks making decisions, slavery was prevalent and pervasive at the time. It was something distant for those who did not own slaves and how people of color interacted. It’s that way today. There are so many issues that we’re dealing with right now where people in Congress are not exposed to the issues the same way that the electorate is. So I didn’t have a problem with it. I understood it.

As long as there is enough film out there to cover the subject matter. And I think this institution of slavery is well covered now. I don’t say well covered meaning we don’t need more films about it. We’re talking about an institution that lasted for nearly 200 years. I think there are any number of stories that could be told, but I think one has to look at these stories individually and not looking at any of them as having to do the job of telling this environment in its totality because every film will come up short if that’s the measurement.

How do you see the state of affairs in Hollywood when it comes to people of color?

I would say, in my opinion, it has gotten much better over the last year and a half, two years. If you go back, you look at a variety of films. You look at Flight with Denzel, you look at Red Tails, Think Like a Man, or Halle Berry’s film, The Call. Certainly films like Fruitvale, The Butler, Mandela: Long Walk to Freedom, 12 Years a Slave, I have this film about Jimi Hendrix coming up—you definitely see a variety of films of people’s color in various positions in front of the camera, behind the camera. Life of Pi, I would put in there as well. I think we have a long way to go in terms of numbers. I don’t believe there should be a quota system by any means, you know, a white filmmaker makes a film, a black filmmaker makes a film. I think also we have to be mindful when we talk about peoples’ color. If you do look at the numbers and even attempt to put together any kind of equation, there are certainly not enough Hispanics who have an opportunity to tell their stories, or stories at all. It doesn’t necessarily have to be their stories, just opportunities to work in film. Although you see Alfonso Cuaron this year with Gravity, which I think is fantastic both as a film and a reminder to people that we can do other things. More women working in film, in front of the camera, behind the camera, in different roles, and not just for ladies who are between twenty and thirty-nine.

There’s a lot of work that needs to be done, and part of that comes from people who make films and realizing there is an audience that out there that is willing to support on a weekly basis. We just had Best Man Holiday open two weeks ago and one of the things that really bothers me is that a film like that comes out and does exceptionally well, and the reportage out here is that it over-performed. And that really bothers me because it’s not that it over-performed; there was an audience that is strong, that has money, and wants to see films that, don’t even have to necessarily involve the black American experience, but they’re fun, they’re funny, they’re different and they’re with people who look like us. And when folks report that it over-performed it’s almost as if saying this was an accident. It wasn’t supposed to happen, it’s an aberration and it’s not going to happen again. And when people use that line out here week in and week out you are just reinforcing the idea that this is an audience that exists and thrives and is willing to support film in any fashion. I think we need to get past that kind of language. I think we have to understand that America is changing, that the world is changing, and that we need to build films for everybody. It’s just good business sense, that’s a reality. It’s just good business sense. There are those of us who work in this business who want to thrive.

What’s next for you? What are you working on now?

I have this film coming out in May called Always by My Side that is about a year in the life of Jimi Hendrix with Andre Benjamin in the lead, and we opened in Toronto with 12 Years a Slave, which was a pretty amazing weekend for me. Both films were well received, and Andre is absolutely phenomenal in this part. And for a guy who has accomplished a lot in his career, he’s really taking it to the next level, so I’m very excited about that. And with 12 Years, there’s still a long way to go with this. Awards season is coming up. All of us involved in the film are very hopeful that our hard work and Solomon’s story will continue to get noticed and recognized.