A caricature of Russian serfs

By: Katherine E. Ruiz-Díaz

Introduction

Serfdom in Europe can be traced back to the 11th century. This type of feudalism spanned throughout Europe, declining in Western Europe around the 14th century with the Renaissance, but increasing in Central and Eastern Europe, a phenomenon sometimes known as “later serfdom.” Until it was abolished in 1861, serfs -as they were known- in Russia were bonded to their masters in a certain type of modified slavery. Known as the Russian Empire, a term coined by Peter I the Great, this time period is an era of reform for the peasant serfs in the Russian countryside. In this research guide, the period of time attempted to be covered is between 1721, at the beginning of what is know as the Russian Empire, and the year 1861, when under the rule of czar Alexander II serfdom was abolished.

Many elements influenced this turn of events for serfs, from Enlightenment ideas that found their way into the Russian crown to general apathy towards American slavery at the time. Nevertheless, this research guide does not focus mainly on the end of serfdom, but on compiling information about the lives of peasant serfs before the year 1861. The main purpose of this page is to compile information, primary sources, and historical analysis that presents Russian peasants as socio-economic beings, whose lives -otherwise seen as insignificant- made the pages of history and influenced the writings of literary circles at the time.

Agricultural Economy in Rural Russia

Serfdom, as any form of feudalism, was based on an agrarian economy. Day after day, serfs worked the land of their lords, barely leaving time to cultivate the land allotted to them to take care of their family. The lord’s land was divided by the peasant commune (obshchina or mir), into large fields worked on a rotation crop system. Each field was divided into strips and each family given so many strips in each field according either to the number of male workers in the family or the number of mouths to feed. It was this control of “their” land which led to the mistaken, but deep-rooted peasant belief that “we belong to the masters but the land is ours.”

“The Russian Agrarian Question” from The Russian Peasantry: Their Agrarian Condition, Social Life, and Religion

- While a rather old source, Kravchisnskii’s book chapter “The Russian Agrarian Question” can provide the reader a good overview on Russian agriculture under serfdom. The interested reader and/or researcher can find a fairly deep analysis on the economical validity of serfdom and cash crops. One must keep in mind that this was chapter (and book) was written after the emancipation of serfdom, a period where many authors from different disciplines were very critical on the economic structure and very purpose of serfdom, while at the same time dealing with at term coined as “the peasant question.”

- Kravchinskii, Sergei M. “The Russian Agrarian Question.” The Russian Peasantry: Their Agrarian Condition, Social Life and Religion. 1888. Reprint, Westport, CT: Hyperion Press, Inc., 1967. 1-71.

“The Peasant and the Village Commune” from The Peasant in Nineteenth-Century Russia

- In this chapter of The Peasant in Nineteenth-Century Russia, Francis M. Watters presents a picture of the world of the peasant cultivator and his deep relationship with the land he worked. The author of this chapter focuses on the village commune (obshchina or mir) as an institution that governed peasant life, assessing his obligations towards his land and his lord, and guarding his rights.

- Vucinich, Wayne S. “The Peasant and the Village Commune.” The Peasant in Nineteenth-Century Russia. Stanford, Calif.: Stanford University Press, 1968. 133-157.

“Russian Agriculture in the Last 150 Years of Serfdom” (Journal Article)

- This article provides a rather complete economic history on the state of Russian agriculture. Spanning from the rule of Peter I to the rule of Alexander II, Blum provides a complex analysis on the statistics of crop cultivation, comparing Russian serf production to other areas of Europe. At the same time, the author gives a substantial portrayal of the poor technological conditions under which both serfs and half-free peasants had to work under, among other things. From this journal article, the reader will get a view of serfdom both from an agricultural and economic perspective.

- Blum, Jerome. “Russian Agriculture in the Last 150 Years of Serfdom.” Agricultural History 34, no. 1 (1960): 3-12.

“Peasants On the Move: State Standard Resettlement in Imperial Russia, 1805-1830s” (Journal Article)

- Part of the driving force of Russian agriculture was the constant migration of serfs/peasants, an action usually issued by the imperial government. In this article, Sunderland provides an analysis on government-issued reforms, forced migration patterns, and the impact these produced on peasant everyday-life, all this provided through analysis of archives of the time. Furthermore, one can be able to establish a connection between the needs of the state and how these affected serfs, both economically and socially.

- Sunderland, Willard. “Peasants On the Move: State Standard Resettlement in Imperial Russia, 1805-1830s.” Russian Review 52, no. 4 (1993): 472-485.

“О причинах возникновения крепостничества в России” (Webpage Journal Article)

- Serfdom was a phenomenon that was not marked by specific historical catalysts. On the contrary, different conditions of social life and the economy of the time came together to give way to this type of feudalism. In this article, by the journal Scepsis, Milov provides a long analysis in which he discusses certain socio-economic reasons for the surfacing of serf agriculture -and serfdom as an economic structure- in Russia. The source is in Russian.

- Милов, Леонид. “О причинах возникновения крепостничества в России.” Scepsis. http://scepsis.ru/library/id_1588.html. (accessed November 25, 2012).

“Peasant Communes and Economic Innovation” from Peasant Economy, Culture, and Politics of European Russia, 1800-1921

- In this first chapter of the book, Kingston-Mann discusses in an essay the different economic models tried to put into use at peasant communes. While these “economic innovations” were experimentally put into practice during the 1870s and 1880s, these theoretical models were created during the years before emancipation. More than dealing with the “peasant question,” Kingston-Mann shows how reformers dealt with productivity, economic backwardness, and peasant thinking on private -versus otherwise communal- property.

- Kingston-Mann, Esther, Timothy Mixter, and Jeffrey Burds. “Peasant Communes and Economic Innovation: A Preliminary Inquiry.” Peasant Economy, Culture, and Politics of European Russia, 1800-1921. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1991. 23-51.

Peasant Society and Politics

The peasantry had a culture of its own, often very different to the French speaking and western educated one of their masters. This culture was based round village life, the seasons of the agricultural year, folklore and the church. Many historians, following commentators like Belinsky or Stepniak (Kravchinsky), have argued that the Orthodox church had little real impact on peasant life, apart from their carrying out the fasts and rituals, and that peasants were superstitious and illiterate and not genuinely religious.

Society and Life

“The Peasant Way of Life” from The Peasant in Nineteenth-Century Russia

- The Russian peasant way of life was full and abundant in its own way. In this essay, Mary Matossian provides a description of the peasant way of life under normal conditions around 1860, on the eve of emancipation. She covers various aspects of peasant life, like housing, economy, diet, fashion, family life, and village life.

- Vucinich, Wayne S. “The Peasant Way of Life.” The Peasant in Nineteenth-Century Russia. Stanford, Calif.: Stanford University Press, 1968. 1-40.

“Micro-Perspectives on 19th-Century Russian Living Standards” (Work in Progress/Presentation)

- While this is a work in progress, Dennison and Nafzinger discuss the living standards of the Russian peasants in the countryside rather than in large cities, like Moscow and St. Petersburg, from a sociological point of view. By using a rather representative village as their case study, they use this information to measure the living standards of the peasant in health, education, and other “non-market goods.” In their section “Pre-Emancipation Living Standards,” the authors take into accounts many factors (like serf accounts to their lords, demographics, wages) to present a picture of the quality of life of the Russian peasant during the time period this guide covers.

- Dennison Tracy, and Steve Nafzinger. “Micro-Perspectives on 19th-Century Russian Living Standards.” Paper presented at the annual meeting of the Social Science History Association, Chicago, IL, November 15-18, 2007.

“Россия крепостная, история народного рабства” (Website)

- Translated as “Serfdom in Russia, the Story of National Slavery,” this is an anthology that compiles information on serf conditions and their relations with their lords. Tarasov manages to recollect different aspects of how serfdom came about, the conditions under which they had to live in, among other things. The section to be pointed out would be Chapter 3 (“Усадьба и ее обитатели: дворяне и дворовые люди”,) where Tarasov presents the disparity between serf and lord, and how by emulating a Western culture the Russian elites managed to alienate the common peasantry. While the author covers a more broad time period of serfdom, this Westernization occurred during the time of Peter the Great, at the very inception of Imperial Russia.

- Тарасов, Борис. “Россия крепостная, история народного рабства.” Samlib. samlib.ru/a/ali_s/rabstwo.shtml (accessed November 24, 2012).

“Everyday Forms of Resistance: Serf Opposition to Gentry Exactions” from Peasant Economy, Culture, and Politics

- This article explores the validity of the concept of everyday resistance as a way to understand Russian serfdom. Rodney Bohac goes on to examine the actions of serfs living on an early-nineteenth-century Russian estate, through petitions and managerial reports sent from the estate to the absentee owner. Furthermore, the author wants to show how peasants used forms of resistance -dissimulation, petty theft, work slowdowns, and flight- to mitigate the effects of money rent (obrok.) Bohac also presents how these forms of resistance did have effects on the production of crops during the 1810s and 1820s.

- Kingston-Mann, Esther, Timothy Mixter, and Jeffrey Burds. “Everyday Forms of Resistance: Serf Opposition to Gentry Exactions”. Peasant Economy, Culture, and Politics of European Russia, 1800-1921. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1991. 236-260.

Four Russian Serf Narratives

- This book gathers four narratives composed by Russian serfs, either during serfdom or after the emancipation of serfs. The stories are set chronologically in the book, all of experiences under serfdom. The first one, composed in 1785, relates the story of Nikolai Smirnov in his own words after being caught trying to escape his lord. The second story is more of poetic prose written by a anonymous peasant known as Petr O. The third story comes from ex-serf Nikolai Shipov (1881), in which he accounts his attempts to escape from being bonded to a lord, and finally ending in his escape. The book ends with a story told from the perspective of an ex-serf woman, M. E. Vasilieva, in which he narrates her life as a girl under serfdom (1911). Besides being (conveniently) translated from Russian to English, this compilation offers first-hand accounts of serfs from different areas of the country and under different, individual conditions.

- MacKay, John. Four Russian Serf Narratives. Madison, Wis.: University of Wisconsin Press, 2009.

Life Under Russian Serfdom: The Memoirs of Savva Dmitrievich Purlevskii, 1800-1868

- This is the memoir of Savva Dmitrievich Purlevskii, who wrote his life story after his death in 1868. In this book, he narrates his entire life, a man that lead a rather ordinary life as a serf. This is a story of how he manages to escape serfdom to become a merchant, and these experiences are retrospectively told once he is outside of the village life and free from the hold of his lord.

- Purlevskii, Savva Dmitrievich, and Boris B. Gorshkov. A Life Under Russian Serfdom: Memoirs of Savva Dmitrievich Purlevskii, 1800-1868. Budapest: Central European University Press, 2005.

The Russian Museum (Website)

- This is the link for a small part of the folk art section of the Russian Museum of Art. Through their art, one can open yet another window into peasant-serf life in this time period.

- “Folk Art.” The Russian Museum. http://www.rusmuseum.ru/eng/collections/folk_art/ (accessed November 27, 2012).

Peasants, Serfs, Soldiers

Serfs, as it usually happened in a feudal system, could be conscripted and sent off to war by their lords. In fact, a male serf could be sent into the imperial army as punishment for “insubordination,” and the parameters for this charge were established by the individual serf lords. In this segment tries to collected different sources that portray serfs as soldiers of Imperial Russia, collecting different media content and pieces of historical analysis.

“The Peasant and the Army” from The Peasant in Nineteenth-Century Russia

- While the majority of records compiling information about soldier conditions is from the years after 1905, the pre-reform army of the nineteenth century was rather different. In this essay, John S. Curtiss goes on to portray an image of a Russian army that was mostly composed of peasant-serfs. Unlike the Russian army troops that were controlled by the government during the 1900s, this peasant army was one composed of serfs that had strong aversion for the army, its harsh discipline, and brutal treatment, which usually resulted in desertions and suicides among serfs.

- Vucinich, Wayne S. “The Peasant and the Army.” The Peasant in Nineteenth-Century Russia. Stanford, Calif.: Stanford University Press, 1968. 108-132.

“Отслужил солдат” (“Soldiers Had Served the Czar”)

A traditional Russian lament, and source of many different adaptation, this song portrays the story of an old soldier coming home after 25 years of serving the czar. As the lyrics show, when he returns to his home, he finds his beloved wife to be dead and the life he once had completely changed and ruined. Lyrics in both English and Russian provided.

Translation of Lyrics to English:

The soldier has served his harsh duty

His patriotic duty, his hard duty

Twenty years he served, and another five

Before the general gave him his leave

And the soldier went to familiar lands

His chest full of medals, his hair all gray

On the porch, his young wife sits

As if twenty years had not gone by

Not a wrinkle on her face

Not a gray hair in her youthful braids

Looked the soldier upon his wife

And said the soldier these bitter words

“Looks like you, my wife, have had a good life,

had a good life, have not aged!”

And she says to him from the porch,

Says from the porch, eyes full of tears:

“I am not your wife lawful, I am your daughter, orphaned.

Your wifе is in the cold ground,

Under the birch tree, five years now.”

And the soldier went, in the house he sat.

Young wine, he asked to be brought.

Drank all night, the soldier, down his cheeks

either wine dripped, or maybe tears

“Social Misfits: Veterans and Soldiers’ Families in Servile Russia” (Journal Article)

- In this article, Wirtschafter examines the relationship between military service and social categorization in Imperial Russia prior to the introduction of universal conscription in 1874. Focusing upon the lower military ranks and the role of service obligations and opportunities in blurring social boundaries it analyzes the ambiguous status of retired soldiers, soldiers’ wives,and the illegitimate children of the latter, with an eye toward the larger problem of social definition.

- Wirtschafter, Elise Kimerling. “Social Misfits: Veterans and Soldiers’ Families in Servile Russia.” The Journal of Military History 59, no. 2 (1995): 215-235.

“Russian Army of the Napoleonic Wars” (Website)

- The Napoleonic Wars were an event that marked the pages of Russian history during its 10-year period (1805-1815.) While in the large scale they marked the victory of Europe against Napoleon Bonaparte at the Battle of Waterloo, it also marked the lives of thousands of serfs-turned-soldiers. In this webpage, one can learn the hardships serfs had to withstand, and the discipline -among many other things- they had to undergo to serve czar, lord, and country.

- “Russian Army of the Napoleonic Wars.” Napolun. http://www.napolun.com/mirror/napoleonistyka.atspace.com/Russian_army.htm (accessed November 20, 2012).

“Peasants in Uniform: The Tsarist Army as a Peasant Society” (Journal Article)

- While in this article Bushnell explores the condition of the peasant-soldier after the emancipation of serfdom, within his analysis one can see the continuing trend even after peasants no longer were bonded to a lord.

- Bushnell, John. “Peasants in Uniform: The Tsarist Army as a Peasant Society.” Journal of Social History 13, no. 4 (1980): 565-576.

Religion and Belief

“Popular Religion” from The Russian Peasantry

- In this section of the book, Kravchinskii raises the question: “Are the Russian peasants so very religious?” He claims for peasants to be “Christ-like,” following an idea of religion that includes “pan-human” morals rather than really having knowledge of the inner workings of Christian theology. The author mostly covers the Christian Orthodox peasantry.

- Kravchinskii, Sergei M. “Popular Religion.” The Russian Peasantry: Their Agrarian Condition, Social Life, and Religion. 1888. Reprint, Westport, CT: Hyperion Press, Inc., 1967. 208-235.

“The Peasant and Religion” from The Peasant in Nineteenth-Century Russia

- The etymology of the word for peasant in Russian –krest’ianin– is from the Old Russian word for “Christian.”While others argue that the Russian peasantry was persistently yet superficially religious, Donald W. Treadgold argues that there is not enough evidence to support this claim. He, then, goes into a revision and analysis of the (scarce) literature on the subject, while going deep into Russian folk culture to show a more round and complete analysis of peasant religion.

- Vucinich, Wayne S. “The Peasant and Religion.” The Peasant in Nineteenth-Century Russia. Stanford, Calif.: Stanford University Press, 1968. 72-107.

“Religion and Expressive Culture” (Website)

- This website provides a rather general view of peasant religion, rituals, and integration with everyday life. While it is not exactly complete, this website is a good starting point to learn about peasant religion, but it is recommended to complement this information with other books on the subject (see above).

- “Religion and Expressive Culture – Russian Peasants.” Countries and Their Cultures. http://www.everyculture.com/Russia-Eurasia-China/Russian-Peasants-Religion-and-Expressive-Culture.html (accessed November 20, 2012).

Peasant Women in Rural Society

In an agrarian-based serf society, women were at a disadvantage. For the lords, serf women were seen as a commodity, a means for reproduction and increased revenue; their treatment as such was very similar to European treatment of African slaves, retarding the concept of “rights in persons” to benefit themselves through slave labor. At the same time, serf women were subjugated in their own home, belonging to a patriarchy that also extended into the inner workings of serf society.

“Empresses and Serfs, 1695-1855” from A History of Women in Russia: From Earliest Times to the Present

- This segment of the book shows how attempts to bring with the emancipation of serfdom reforms for a more open attitude towards women in society failed. The question to have in mind while reading this would be if serfs had better conditions under “the Age of Empresses,” or if there was no difference at all. While it does not touch on the subject of serf women specifically, it is interesting to read and observe that serf-czar relationship.

- Clements, Barbara Evans. “Empresses and Serfs, 1695-1855.” A History of Women in Russia: From Earliest Times to the Present. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2012. 64-111.

“Victims or Actors? Russian Peasant Women and Patriarchy” from Peasant Economy, Culture and Politics

- In this essay, Worobec paints a good picture of the rigidity of village patriarchy. In every sphere of serf social life, women were subjugated, following certain societal patterns based on preconceived notions of male and female roles. While marriage was compulsory, it was an event in a woman’s life that was both wanted and dreaded. Furthermore, this essay attempts to cover the different roles and aspects of a woman’s life in a peasant village, from matters like premarital chastity to the habit of wife beating.

- Kingston-Mann, Esther, Timothy Mixter, and Jeffrey Burds. “Victims or Actors? Russian Peasant Women and Patriarchy”. Peasant Economy, Culture, and Politics of European Russia, 1800-1921. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University 5Press, 1991. 177-206.

“Widows and the Russian Serf Community” from Russia’s Women: Accommodation, Resistance, Transformation

- In this section, by Rofney D. Bohac, the reader can get a picture of the life of peasant widows. Bohac shows how both views of the widow contain truth: widows could be alone and vulnerable, but also managing a household by themselves. It was a matter whether she overcame the pressure of the patriarchal society in which she lived. The author also discusses a widow’s economic situation, property rights, and her living conditions.

- Clements, Barbara Evans, Barbara Alpern Engel, and Christine Worobec. “Widows and the Russian Serf Community.” Russia’s Women: Accommodation, Resistance, Transformation. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1991. 95-112.

“The Peasant Woman as Healer” from Russia’s Women: Accommodation, Resistance, Transformation

- This section of the book shows Russian women’s roles as healers and midwives, a tradition long before the appearance of professionalized medical practitioners in the Russian countryside. One can observe the kind of jobs peasant-serf women could have, and how they managed to do well in it.

- Clements, Barbara Evans, Barbara Alpern Engel, and Christine Worobec. “The Peasant Woman as a Healer.” Russia’s Women: Accommodation, Resistance, Transformation. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1991. 148-162.

“Female Serfs in the Performing World” from Women in Russian Culture and Society, 1700-1825

- In this essay, Richard Sites shows how peasant women could obtain a certain social mobility if they chose to become actresses. While they had to endure the social connotations of choosing this profession and the abuses of their owners, one can observe an outlet for serf women to escape their lives in the countryside, for better or for worse.

- Rosslyn, Wendy, and Alessandra Tosi (ed.). “Female Serfs in the Performing World.” In Women in Russian Culture and Society, 1700-1825. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2007. 24-38.

The End of Serfdom

The abolition of serfdom was a turning point in Russian history. The years that followed 1861, until the fall of the empire in 1917, are considered one of the most reformist years in Russian history. In one way or another, the emancipation of serfs opened the floodgates to the events leading to 1917 and its aftermath, giving these peasants more freedom to be organized. In this segment, while some background information is provided on important czars of the era for serfdom, Catherine II and Alexander II, the main focus is the collection of works analyzing the end of serfdom.

Catherine II the Great (Екатерина II Великая) and the Enlightenment

Despite the professed distaste of serfdom by Catherine II the Great and her enlightenment ideas, the institution expanded considerably under her reign. While Catherine continued to modernize Russia along Western European lines, military conscription and economy continued to depend on serfdom, and the increasing demands of the state and private landowners led to increased levels of reliance on serfs. This was one of the chief reasons behind several rebellions, including the large-scale Pugachev’s Rebellion of cossacks and peasants.

Alexander II the Liberator

Under Alexander II‘s rule, important changes were made in legislation. The existence of serfdom was tackled boldly, taking advantage of a petition presented by the Polish landed proprietors of the Lithuanian provinces and, hoping that their relations with the serfs might be regulated in a more satisfactory way, he authorized the formation of committees “for ameliorating the condition of the peasants,” and laid down the principles on which the amelioration was to be effected. The emancipation was not merely a humanitarian question capable of being solved instantaneously by imperial ukase. It contained very complicated problems, deeply affecting the economic, social, and political future of the nation. On 3 March 1861, 6 years after his accession, the emancipation law was signed and published.

Emancipation of Serfdom in Russia

Russian Peasants and Tsarist Legislation on the Eve of Reform: Interaction between Peasants and Officialdom, 1825-1855

- A detailed examination of three cases, David Moon explores peasant interactions with the state during the last decades of serfdom. One can see how peasants interpreted orders from those above them, and how -whether intentionally or unintentionally- they simply ignored imperial authority. Moon presents the idea of a “rational peasant” that was neither fooled nor (mis)guided by utopic ideas surfacing at the time, but rather an individual being just trying to survive in the conditions given to him.

- Moon, David. Russian Peasants and Tsarist Legislation on the Eve of Reform: Interaction Between Peasants and Officialdom, 1825-1855. Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire: Macmillan Press, in association with the Centre for Russian and East European Studies, University of Birmingham, 1992.

The End of Serfdom: Nobility and Bureaucracy in Russia, 1855-1861

- In this book, Field attempts to explain how an old system of bondage such as serfdom came to an end. Rather than focusing on the peasant, as other books in this research guide, this book focuses more on the other side of the coin: the nobility and the government. Thus, The End of Serfdom goes deep into analyzing the reaction of nobles to this reform, and how Russian bureaucracy was changed because of the emancipation of serfs.

- Field, Daniel. The End of Serfdom: Nobility and Bureaucracy in Russia, 1855-1861. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1976.

“The Peasant and the Emancipation” from The Peasant in Nineteenth-Century Russia

- In this essay, Terence Emmons provides an analysis to the events and conditions that gave way for czar Alexander II to abolish serfdom in Imperial Russia. At the same time, he discusses how the state coped with the lost of this massive economic income, and how lords in the countryside attempted to establish strong resistance against the changes imposed by the empire.

- Vucinich, Wayne S. “The Peasant and the Emancipation.” The Peasant in Nineteenth-Century Russia. Stanford, Calif.: Stanford University Press, 1968. 41-71.

Emancipation of the Russian Serfs

- This book, compiled by Emmons, presents a series of essays that can present to the reader a general idea of the atmosphere of the time when serfdom was abolished in Russia. Emancipation of the Russian Serfs provides the historical background for the period leading to emancipation, the economic background of the different objectives attempted to be achieved by the different social classes in play, the motives for reform, and the final results that came with that reform.

- Emmons, Terence. Emancipation of the Russian Serfs. New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston, 1970.

“The Emancipation of the Russian Serfs, 1861: A Charter of Freedom or an Act of Betrayal?” (Web Journal Article)

- This link provides a general overview on the end of serfdom, Alexander II’s role, and the significance of emancipation. It is a good article because, while one can complement with information from other sources as the ones provided above, it also provides sources for further reading.

- Lynch, Michael. “The Emancipation of the Russian Serfs, 1861: A Charter of Freedom or an Act of Betrayal?.” History Today. www.historytoday.com/michael-lynch/emancipation-russian-serfs-1861-charter-freedom-or-act-betrayal (accessed November 19, 2012).

Representations in Literature

As said before, peasant life served as inspirations for works of literature. Most of the literature during this time period criticized or satirized in some way the conditions of serfs and the socio-economic structure of serfdom. While many works of this time were censored, this section attempts to collect works that incorporated serfdom -and serfs as characters- into their plot. Works analyzing literature of the time and its use of peasants also appears in this segment.

Nikolai Gogol — “Dead Souls” (Мёртвые души, 1842)

In the Russian Empire, before 1861, landowners could buy, sell, or mortgage their serfs. To count serfs (and people in general), the measure word “soul” was used. The plot of the novel relies on “dead souls” (i.e., “dead serfs”) which are still accounted for in property registers. This story follows the exploits of Chichikov, a gentleman of middling social class and position. Chichikov arrives in a small town and quickly tries to make a good name for himself by impressing the many petty officials of the town. Despite his limited funds, he spends extravagantly on the premise that a great show of wealth and power at the start will gain him the connections he needs to live easily in the future. He also hopes to befriend the town so that he can more easily carry out his bizarre and mysterious plan to acquire “dead souls.” Online English version of the text is provided.

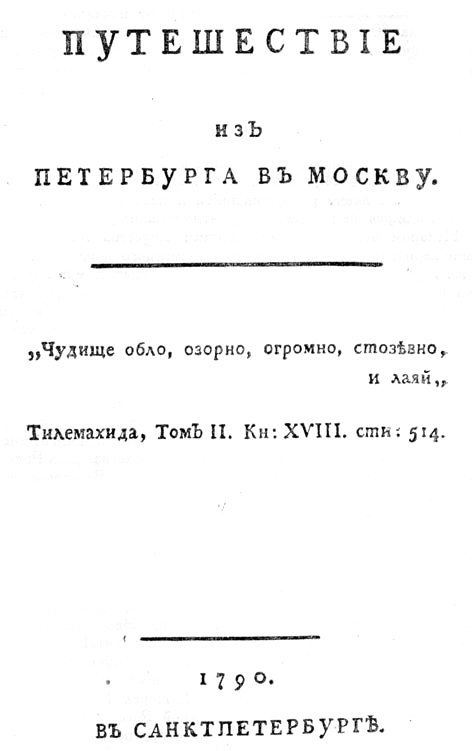

Alexandr Nikolayevich Radishchev — “Journey From St. Petersburg to Moscow” (Путешествие из Петербурга в Москву, 1790)

This book is Radishchev’s most famous, even though it was banned and he himself was exiled to Siberia. Often described as a Russian Uncle Tom’s Cabin, it is a polemical study of the problems in the Russia of Catherine the Great: serfdom, the powers of the nobility, the issues in government and governance, social structure, and personal freedom and liberty. In the book, Radishchev takes an imaginary journey between Russia’s two principal cities; each stop along the way reveals particular problems for the traveler through the medium of story telling. Published during the period of the French Revolution, the book borrows ideas and principles from the great philosophers of the day relating to an enlightened outlook and the concept of Natural Law.

Nikolai Karamzin — “Poor Liza” (Бедная Лиза, 1792)

Known as one of the best exponents of Russian sentimentalism, “Poor Liza” is the story of a peasant girl that is seduced by a gentleman, whom which she falls in love with, only to be later abandoned. In the end, her heartbreak results in her suicide. Although Karamzin presents an idealized version of a serf, in particular of a peasant woman, it nevertheless shows the influence the lower classes had on character formation and literature. While critics say that the portrayal not as realistic, or even critical, as Radishchev, Karamzin sure presents another view on serfs by a higher strata of Russian society.

Leo Tolstoy — “Anna Karenina” (Анна Каренина, 1878)

This story is set “in the time of the masters” (i.e. under serfdom.) Under barshchina the normal arrangement was for the lord’s land to be divided with an area set aside as demesne or landlord area to be farmed by the peasants, but under whatever orders the landlord laid down. This could mean if, like Tolstoy himself, the landlord was a progressive farmer, that the land was enclosed and machinery could be brought in and new seeds developed. Such a landlord might also introduce schools and other facilities on the estate and try to educate the peasantry in western farming methods. Levin in Anna Karenina is based on Tolstoy’s own experience and shows how difficult such projects could be. The rest of the farm would be handed over to the peasants for their own use. Russian and English versions of the text provided.

“The Peasant in Literature” from The Peasant in Nineteenth-Century Russia

- In this segment of the book, Donald Fanger discusses the appearance of peasants in literature of the 19th century. The author of this essay argues that it is difficult -if not almost impossible- to find literature of the time that gives a truthful depiction of peasant life; rather, authors of the time worked of stereotypes and commonplace conventions, even those who came from peasant backgrounds. Fanger discusses works of authors like Radishchev, Karamzin, Tolstoy, (shown above, ) and Dostoevsky. He also goes into the different stereotypes and roles serfs played in literature.

- Vucinich, Wayne S. “The Peasant in Literature.” The Peasant in Nineteenth-Century Russia. Stanford, Calif.: Stanford University Press, 1968. 231-262.

“Description of peasantry in the main works of Russian prose literature from the mid-nineteenth century to 1917” (Thesis Paper)

- While mainly in Russian, this paper -a thesis work by Sophia Rosovsky- explores the description of peasantry in Russian prose literature from the second half of 1840s to 1917. All material is sub-divided into chapters; each chapter discusses an individual writer, except the fourth chapter which considers the raznochintzy writers.

- Rosovsky, Sophia. “Description of peasantry in the main works of Russian prose literature from the mid-nineteenth century to 1917.” MA diss., The University of British Columbia, 1973.

Serfdom, Society, and the Art in Imperial Russia: The Pleasure and the Power

- In this interesting book, Stites analyses different aspects of the arts, from sheet music to opera. While the title might suggest so, he does not go into folk culture and serf art, but into a deep analysis of how the Russian elite interpreted serf and peasant life. Moreover, he focuses on countryside elites that, in one way or another, tried to incorporate their perceptions and outside observations of peasant everyday-life into their works. Was it a homage? Was it a mockery? At the same time, the author discusses other factors, like social stature and rank distinction within the same elite classes.

- Stites, Richard. Serfdom, Society, and the Arts in Imperial Russia: The Pleasure and the Power. New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press, 2005.

Further Reading

Lord and Peasant in Russia: from the Ninth to the Nineteenth Century

- In this book Jerome Blum goes into depth on the dynamics of serfdom in Russia. Covering a rather large scope, this book was relevant upon its publication in 1961, marking the one hundredth anniversary of the emancipation of the Russian serfs, and it is a book still relevant today. Lord and Peasant is a rather large volume that explores the legal and social evolution of Russia’s predominantly agricultural population, the types of peasant status, and the multifaceted nature of the master-peasant relationship. Blum also makes the argument that it is necessary place serfs front and center in the study of Russian history. This book is considered by many a cornerstone of Russian historiography.

- Blum, Jerome. Lord and Peasant in Russia: from the Ninth to the Nineteenth Century. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1961.

A Social History of the Russian Empire 1650-1825

- This is a rather broad collection of the social history of Russia from before Peter the Great right through to the post-Napoleonic era. While Janet Hartley traces significant developments, she concentrates on two major themes: the relations of society and the state, and the relations between the different social groups. While this book does not focuses on serfdom, it does have segments that give a glimpse into peasant life. What this book does provide is a view of the bigger scheme of what Russian society was, and the observant reader might see how peasant fit into Imperial Russia as a whole.

- Hartley, Janet M.. A Social History of the Russian Empire 1650-1825. London: Addison Wesley Longman, 1999.

The Russian Museum of Ethnography (Website)

- The website of the Russian Museum of Ethnography provides a decent display of the different cultures of the people in the countryside, from traditional agriculture to attire and customs. In addition, this website can serve as both a written and visual source of information on Russian peasants.

- “The Russian Museum of Ethnography.” The Russian Museum of Ethnography. http://eng.ethnomuseum.ru/ (accessed November 27, 2012).