Theory is dead. Well, so I am told. Since the 1990s critics, authors and writers such as David Bordwell, Murray Pomerance and many others have stressed the need to steer film theory in a new direction, whether it be film-philosophy, neo-formalism or another approach (if not theory altogether). Thankfully, if theory is not completely dead (which I hope that it is not) the often obfuscatory, impenetrable style that characterized the worst aspects of it may be. Implicit in the ongoing debate about the death of theory, is a question of cinephilia and its relationship to film criticism. The resurgence of cinephilia in film studies, while giving birth to an already bloated field of study, has also reminded scholars of the importance of style in the development of film criticism. While prone to excessive use of superlatives, what were the cahiers critics if not great stylists? Finding an adequate way of communicating both one’s emotional and intellectual thoughts on film are one of the many threads in a great new collection, The Language and Style of Film Criticism edited by Alex Clayton and Andrew Klevan. Concerned with the form of criticism, each essay elegantly dances with unique style: fragmentary thoughts are cloaked as sentences while fiction and description melt into each other and overlap with analysis. There is such variation and passion in these essays, that while not all are transportive the collection feels alive.

Theory is dead. Well, so I am told. Since the 1990s critics, authors and writers such as David Bordwell, Murray Pomerance and many others have stressed the need to steer film theory in a new direction, whether it be film-philosophy, neo-formalism or another approach (if not theory altogether). Thankfully, if theory is not completely dead (which I hope that it is not) the often obfuscatory, impenetrable style that characterized the worst aspects of it may be. Implicit in the ongoing debate about the death of theory, is a question of cinephilia and its relationship to film criticism. The resurgence of cinephilia in film studies, while giving birth to an already bloated field of study, has also reminded scholars of the importance of style in the development of film criticism. While prone to excessive use of superlatives, what were the cahiers critics if not great stylists? Finding an adequate way of communicating both one’s emotional and intellectual thoughts on film are one of the many threads in a great new collection, The Language and Style of Film Criticism edited by Alex Clayton and Andrew Klevan. Concerned with the form of criticism, each essay elegantly dances with unique style: fragmentary thoughts are cloaked as sentences while fiction and description melt into each other and overlap with analysis. There is such variation and passion in these essays, that while not all are transportive the collection feels alive.

Often introductions emerge as overly long explanations that merely preface the coming essays. In recapitulating essays they become a sort of Cliffs Notes for the collection. Pulling in a range of critics, from Camille Paglia and Raymond Bellour to Stanley Cavell and Andrew Britton among others, Klevan and Clayton’s introduction, rather than summarizing the collection, lays out a series of questions, concerns and hopes about the form of film criticism, all the while pulling out and analyzing the way different authors construct arguments. Of course the important, simple truths are often those that are forgotten. Klevan and Clayton mine some of those truths and bring them out in the introduction reminding readers that “evaluation is not simply something one might do, something optional; it is intrinsic to the viewing experience” (5). What establishes this introduction and thus the entire collection as both enlightening and uplifting is the sense of levity in the writing; this is an introduction that seems to take Cavell’s notion of perfectionism and reproduce it in its very form. Without question, the hope and belief in criticism-as-art permeates each essay in this collection.

Rarely does a sentence sputter out, rarely does a thought fade into the ether, rarely is an insight not gleamed from this poetic prose. Perhaps all the more impressive is that the authors do not attack any of the easy targets often raised as the enemy of less academic critics (post-structuralism, Lacanian psychoanalysis, cultural studies). This introduction instead opts to investigate, citing V.F. Perkins the “important problem with oneself of finding the words that fit ones sense of the moment or the movie” (19). In many ways it is a replay of Emerson’s seemingly doomed quest of communicating experience. As Clayton and Klevan elaborate: “The challenge for the critic is not simply to surrender to platitudes about the undecided, but to attempt to specify the particularity of the indefinite” (21). The introduction promises an investigation of language and style with such clarity and perception one wonders why there has not been more literature on this material already.

We have been introduced, now: how to begin? Alex Clayton’s first essay begins on unstable grounds attempting to highlight and dismantle the criticism provided by Bordwell and Thompson in Film Art. Clayton’s claims are pointed and often funny; of Film Art’s style Clayton writes, “it is as if the film has been sedated, or solved” (29). While certainly not untrue, Bordwell’s status as punching bag for critics makes this seem at first needless, even mean-spirited. As D.N. Rodowick highlighted in his 2007 essay “An Elegy for Theory” “no one’s commitment to good theory building is greater or more admirable” than Bordwell’s.1Thankfully Clayton’s essay evolves instead into a poignant uncovering of the critic as an individual pulled by the poles of time. Clayton suggests that “perhaps criticism can then be considered a communion between the critic’s present and past selves, as well as between the critic and the work” (36). It is a provocative suggestion that establishes the tone for the rest of collection.

The essays that follow create their own communion, one that reveals the experiential qualities and philosophic intricacies to film criticism. Robert Sinnerbrink’s essay “Questioning Style” rejects the false-objective style that dominates film criticism. It is an important addition to the burgeoning literature on film-philosophy. Sinnerbrink’s vision is not only of film-philosophy but of “romantic film-philosophy” (53). Sinnerbrink argues that just as there are grand implications and possibilities for film, film criticism can reveal and uncover truths of the everyday—it can come to elaborate on the question of what film calls thinking. With criticism, Sinnerbrink claims we must “think with, rather than [think] on film” (52).

Adrian Martin reveals in his essay “Incursions” not film-philosophy but instead description-as-philosophy. Martin looks at three critics John Flaus, Shigehiko Hasumi and Frieda Grafe (all unknown to this reader) and how they approach the problem of description: how does one write about a scene in a film without being formulaic, boring, or staid? Martin’s essay lyrically and poetically defends description, turning what is often the worst aspect of an essay into an absolutely engrossing exploration of style. Martin’s essay, which is followed by Andrew Klevan’s essay (“Description”) on critics’ visions of The Magnificent Ambersons, challenges the reader to seize the presentness of film in scene descriptions. Forget textual analysis for a moment, what of textual weaving, textual creation—picture painting. These are the issues of Martin and Klevan’s important essays.

Although it may only be lightly touched on, as though a deft hand fingering the keys of a piano, what subtlety links the essays in this collection is the notion of community. Charles Warren writes that the pleasure of reading criticism may in fact rest in “put[ting the reader] in touch with a community of those who confront and think about art. It is the person looking, listening, and thinking and finding words, who matters – more so than the insights and concepts as such” (143). Citing literary critic R.P. Blackmur, Warren ends his essay, urging critics not merely to embrace their intellect but also their imagination. Criticism may be a sort of communicative science, but it is necessarily and thankfully an imperfect one.

If Warren’s essay highlights the existence of such a community between film, those who watch film and those who read criticism, Lesley Stern’s essay “Memories That Don’t Seem Mine” paints a vivid, almost somatic, portrait of such a community. Filled with fictive interludes Stern moves through Charles Burnett’s Killer of Sheep as light moves into a crystal and is refracted back thousands of different ways. Like the film, Stern’s essay is a series of moments, some elongated, others protracted, all of which seem to carry significance. The essay eschews any straightforward reading, instead unfolding in experimental form. Stern challenges readers and writers to conceive of the essay as a new mode, one which refuses the strict and seemingly false distinctions of fiction and documentary.

Stern seems to stretch the written essay form, but the last essay brings together cinephilic and academic tendencies in highlighting the rise of the video essay. There is something scary about beginning the journey of a video essay. Yet it is perhaps this mysteriousness that makes it so alluring. Christian Keathley’s essay, rather than demystifying, helps organize the “types” of video essays. His essay is an excellent, as he writes, “progress report” on how language and style in film criticism now have new meaning in the video and digital realm. This is a crucial early step in the ever-growing work of video essay-artists such as Keathley and Matt Zoller Seitz.

In their introductory essay Klevan and Clayton claim: “we would like to see film criticism gain a more central place within the academy and develop in more dynamic ways outside it” (24). These essays certainly bridge the split between the academy and the widely-read critic. Rejecting academic jargon and sterile prose, all of the essays strive to open up film studies and urge writers and critics not to become rigid. For every film studies course that requires Bordwell and Thompson’s Film Art, The Language and Style of Film Criticism should be required pairing. While apt for undergraduates, graduates and those outside of academia, there is something even more here for academics and those who may be bitter or tired or exhausted with film studies. This is a clarion call. Wonderfully under the surface of all of these essays is the notion that the history of criticism and theory is not one that is necessarily getting closer to any specific truth. In turning to critics such as T.S. Eliot, Raul Ruiz, V.F. Perkins and Roland Barthes there is still more to open up. Just because these thinkers wrote in a different age does not mean that their writings are insignificant to our age. The history of film criticism is not Whig history. Even further Clayton and Klevan remind us that an essay is never just an essay. An essay is not simply even an organized series of thoughts and feelings—it is something more. That something more is as ineffable and impossible to pin down as film itself. But it exists somewhere in the mystery of criticism as an art form. As evidenced by this collection one of the great beauties of film criticism is the pursuit of those mysteries.

-Nicholas Forster

Sincere thanks to Routledge for a review copy

1. See D.N. Rodowick “An Elegy for Theory” October No. 122, Fall 2007, pp. 91–109.

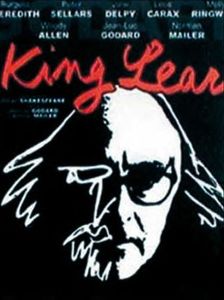

Godard’s King Lear (1987) oscillates between being both a mess and a masterpiece. Shunning any straight-reading of the Shakespeare play, Godard, as he did throughout the 1960s, raises questions about the instability of language and the very meaning of art in a society driven by the culture industry. There is no real plot to Godard’s film and King Lear seems only cursorily interested in Shakespeare’s play, and yet Godard cultivates many of the ideas of his earlier films such as Vivre Sa Vie, Made in the U.S.A. and Pierrot Le Fou in a more coherent manner. Taking place after Chernobyl, in a world where art has been destroyed Godard traces William Shakespeare Jr. the Fifth’s attempt to recreate his ancestor’s work. If Godard shows us the breaking down of Paris in Alphaville, in King Lear the world has already been demolished and reborn. Still, even as art is being re-instantiated and reconstituted, Godard’s world is an attritional one.

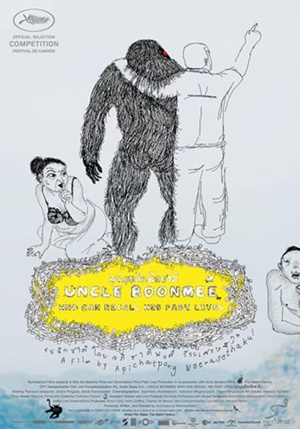

Godard’s King Lear (1987) oscillates between being both a mess and a masterpiece. Shunning any straight-reading of the Shakespeare play, Godard, as he did throughout the 1960s, raises questions about the instability of language and the very meaning of art in a society driven by the culture industry. There is no real plot to Godard’s film and King Lear seems only cursorily interested in Shakespeare’s play, and yet Godard cultivates many of the ideas of his earlier films such as Vivre Sa Vie, Made in the U.S.A. and Pierrot Le Fou in a more coherent manner. Taking place after Chernobyl, in a world where art has been destroyed Godard traces William Shakespeare Jr. the Fifth’s attempt to recreate his ancestor’s work. If Godard shows us the breaking down of Paris in Alphaville, in King Lear the world has already been demolished and reborn. Still, even as art is being re-instantiated and reconstituted, Godard’s world is an attritional one. How do you describe the indescribable? Such a question, lies at the heart of Apichatpong Weerasethakul’s latest film, Uncle Boonmee Who Can Recall His Past Lives. Continuing the trend of so many masters, from Godard and Herzog to Fuller and Hitchcock, Weerasethakul combines both high and low art, in charting the final days of one man’s life. Boonmee is silly, magical, and ridiculous, even wonderful. Yet, the film is more than any of the various loving adjectives; it is unlike anything released in the last decade.

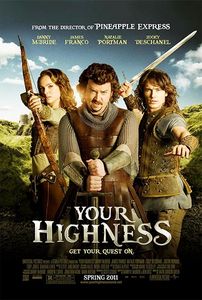

How do you describe the indescribable? Such a question, lies at the heart of Apichatpong Weerasethakul’s latest film, Uncle Boonmee Who Can Recall His Past Lives. Continuing the trend of so many masters, from Godard and Herzog to Fuller and Hitchcock, Weerasethakul combines both high and low art, in charting the final days of one man’s life. Boonmee is silly, magical, and ridiculous, even wonderful. Yet, the film is more than any of the various loving adjectives; it is unlike anything released in the last decade. Once upon a time, about eight years ago, David Gordon Green was America’s most promising young filmmaker. In certain circles, people were calling him the next Malick, and while comparing a twenty-seven year-old with two feature films under his belt to the greatest American filmmaker since Orson Welles may have been a bit excessive, it was not without reason. Aside from some striking aesthetic similarities (a shared interest in poetic realism and Faulkner-esque characters and dialogue), I think George Washington (2000) and All The Real Girls (2003) simply represent the finest beginning to an American’s career since Badlands and Days Of Heaven. I say all of this just to make it clear why I am so utterly disappointed in his latest film, Your Highness. I appreciate the desire to switch it up and make something different, and I thought Green’s first foray into comedy, Pineapple Express, was at least somewhat entertaining, and since then he has directed multiple episodes of Eastbound and Down, my pick for the funniest show currently on television, but everything he learned from those jobs seems to have been forgotten in this mess of a film. Your Highness simply is not funny. At all.

Once upon a time, about eight years ago, David Gordon Green was America’s most promising young filmmaker. In certain circles, people were calling him the next Malick, and while comparing a twenty-seven year-old with two feature films under his belt to the greatest American filmmaker since Orson Welles may have been a bit excessive, it was not without reason. Aside from some striking aesthetic similarities (a shared interest in poetic realism and Faulkner-esque characters and dialogue), I think George Washington (2000) and All The Real Girls (2003) simply represent the finest beginning to an American’s career since Badlands and Days Of Heaven. I say all of this just to make it clear why I am so utterly disappointed in his latest film, Your Highness. I appreciate the desire to switch it up and make something different, and I thought Green’s first foray into comedy, Pineapple Express, was at least somewhat entertaining, and since then he has directed multiple episodes of Eastbound and Down, my pick for the funniest show currently on television, but everything he learned from those jobs seems to have been forgotten in this mess of a film. Your Highness simply is not funny. At all. Looking over my now three-month-old list of the best films of 2010 (which I now realize I should have posted here) I’m noticing how much some of the positioning would change with the benefit of time. The key word there is “some.” There is still no doubt in my mind about the top two films on that list: Apichatpong Weerasethakul’s Uncle Boonmee Who Can Recall His Past Lives and Abbas Kiarostami’s Certified Copy. These films, which picked up the Palme d’Or and the best actress award respectively at Cannes last year, are far and away the most beautiful and engaging pieces of cinematic art that I’ve seen from last year. While Boonmee seemingly never expanded beyond the most limited of releases, which is frankly kind of insulting for a Palme d’Or winner, Certified Copy has finally opened at your local art cinema.

Looking over my now three-month-old list of the best films of 2010 (which I now realize I should have posted here) I’m noticing how much some of the positioning would change with the benefit of time. The key word there is “some.” There is still no doubt in my mind about the top two films on that list: Apichatpong Weerasethakul’s Uncle Boonmee Who Can Recall His Past Lives and Abbas Kiarostami’s Certified Copy. These films, which picked up the Palme d’Or and the best actress award respectively at Cannes last year, are far and away the most beautiful and engaging pieces of cinematic art that I’ve seen from last year. While Boonmee seemingly never expanded beyond the most limited of releases, which is frankly kind of insulting for a Palme d’Or winner, Certified Copy has finally opened at your local art cinema. Matthew McConaughey is extremely likable. When we look back at his most well-known roles—Steve Edison in The Wedding Planner, Ben Barry in How to Lose a Guy in 10 Days, Tripp in Failure to Launch, Connor Mead in Ghosts of Girlfriends Past—it is more than clear that he can play the good-looking, smooth-talking romantic interest that is…well, likable (even if the film isn’t). As he is a member of rom-com royalty, McConaughey’s likability may be one of his best attributes, definitely up there with his willingness to take off his shirt on command. But the actor’s good-looking, smooth-talking ways served him well in his latest film, The Lincoln Lawyer, a crime thriller in which he plays a defense lawyer that is (you guessed it) extremely likable.

Matthew McConaughey is extremely likable. When we look back at his most well-known roles—Steve Edison in The Wedding Planner, Ben Barry in How to Lose a Guy in 10 Days, Tripp in Failure to Launch, Connor Mead in Ghosts of Girlfriends Past—it is more than clear that he can play the good-looking, smooth-talking romantic interest that is…well, likable (even if the film isn’t). As he is a member of rom-com royalty, McConaughey’s likability may be one of his best attributes, definitely up there with his willingness to take off his shirt on command. But the actor’s good-looking, smooth-talking ways served him well in his latest film, The Lincoln Lawyer, a crime thriller in which he plays a defense lawyer that is (you guessed it) extremely likable.  Over the last decade, Simon Pegg and Nick Frost have discovered one of the best formulas in comedy. If you put them, and their quintessential Brittishness, into a scenario from any number of overly serious popular American films, hilarity will probably ensue. Of course, this formula worked best in 2004’s cult classic Shaun Of The Dead, and their next film together, Hot Fuzz, while not quite as hilarious, has grown on me over time, but both of those films were directed by Edgar Wright, as was the British television series Spaced on which they all worked together for the first time. Pegg and Frost’s latest project together, Paul, is their first without Wright, who was busy with Scott Pilgrim. Instead they brought in Superbad and Adventureland’s Greg Mottola and moved the setting from the UK to America. Since the project was announced, I’ve wondered whether or not this radical change in their methods would stifle their humor and hurt the final product, particularly because Paul included an influx of American comedy actors who had not worked with the duo before. The truth is that while the film never comes particularly close to their best work, it’s still generally enjoyable and lesser Pegg and Frost will always be better than whatever other comedies are coming out of Hollywood.

Over the last decade, Simon Pegg and Nick Frost have discovered one of the best formulas in comedy. If you put them, and their quintessential Brittishness, into a scenario from any number of overly serious popular American films, hilarity will probably ensue. Of course, this formula worked best in 2004’s cult classic Shaun Of The Dead, and their next film together, Hot Fuzz, while not quite as hilarious, has grown on me over time, but both of those films were directed by Edgar Wright, as was the British television series Spaced on which they all worked together for the first time. Pegg and Frost’s latest project together, Paul, is their first without Wright, who was busy with Scott Pilgrim. Instead they brought in Superbad and Adventureland’s Greg Mottola and moved the setting from the UK to America. Since the project was announced, I’ve wondered whether or not this radical change in their methods would stifle their humor and hurt the final product, particularly because Paul included an influx of American comedy actors who had not worked with the duo before. The truth is that while the film never comes particularly close to their best work, it’s still generally enjoyable and lesser Pegg and Frost will always be better than whatever other comedies are coming out of Hollywood.

Little Fockers, the third, and hopefully final, film in the trilogy that also includes Meet The Parents and Meet The Fockers, ends with a scene that serves as a surprisingly apt metaphor for the series as a whole. Early in the film, Greg Focker (Ben Stiller) gives a speech in which he recounts some of the mistreatment he suffered at the hands of his father-in-law Jack (Robert De Niro) in the first film. It’s nothing special, but some of the stories are reasonably amusing, just like Meet The Parents. At the end of the film, we see Jack watching the speech on youtube, and because it is so redundant, the speech is not funny the second time around, just like Meet The Fockers. Jack then clicks on an autotuned remix of the speech, which further replicates the same thing, but now it is soulless and mechanical on top of being repetitive, and that seems to describe this film in a nutshell. It’s like the first two, but now anyone with some cheap equipment and a few acting legends willing to embarrass themselves could have done the same thing. I have seen worse comedies this year (Macgruber, anyone?) but none of them have been as astoundingly lazy as Little Fockers. There is not a single joke or situation that isn’t a variation of something that probably wasn’t too funny when it happened in the first movie, and was far less funny when it happened again in the second.

Little Fockers, the third, and hopefully final, film in the trilogy that also includes Meet The Parents and Meet The Fockers, ends with a scene that serves as a surprisingly apt metaphor for the series as a whole. Early in the film, Greg Focker (Ben Stiller) gives a speech in which he recounts some of the mistreatment he suffered at the hands of his father-in-law Jack (Robert De Niro) in the first film. It’s nothing special, but some of the stories are reasonably amusing, just like Meet The Parents. At the end of the film, we see Jack watching the speech on youtube, and because it is so redundant, the speech is not funny the second time around, just like Meet The Fockers. Jack then clicks on an autotuned remix of the speech, which further replicates the same thing, but now it is soulless and mechanical on top of being repetitive, and that seems to describe this film in a nutshell. It’s like the first two, but now anyone with some cheap equipment and a few acting legends willing to embarrass themselves could have done the same thing. I have seen worse comedies this year (Macgruber, anyone?) but none of them have been as astoundingly lazy as Little Fockers. There is not a single joke or situation that isn’t a variation of something that probably wasn’t too funny when it happened in the first movie, and was far less funny when it happened again in the second.