How do you describe the indescribable? Such a question, lies at the heart of Apichatpong Weerasethakul’s latest film, Uncle Boonmee Who Can Recall His Past Lives. Continuing the trend of so many masters, from Godard and Herzog to Fuller and Hitchcock, Weerasethakul combines both high and low art, in charting the final days of one man’s life. Boonmee is silly, magical, and ridiculous, even wonderful. Yet, the film is more than any of the various loving adjectives; it is unlike anything released in the last decade.

How do you describe the indescribable? Such a question, lies at the heart of Apichatpong Weerasethakul’s latest film, Uncle Boonmee Who Can Recall His Past Lives. Continuing the trend of so many masters, from Godard and Herzog to Fuller and Hitchcock, Weerasethakul combines both high and low art, in charting the final days of one man’s life. Boonmee is silly, magical, and ridiculous, even wonderful. Yet, the film is more than any of the various loving adjectives; it is unlike anything released in the last decade.

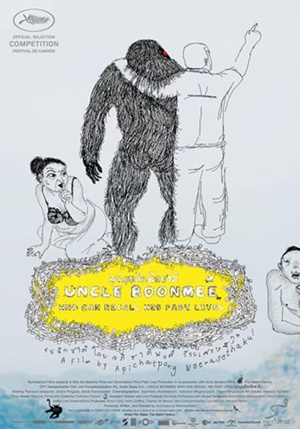

The plot of Boonmee is quite simple. Dying of an ambiguous kidney failure, Uncle Boonmee retreats to a farm where he hopes to relax as his sister-in-law cares for him. One night during dinner, Boonmee is visited by the ghost of his wife. Although she has no corporal body, she appears and chats with Boonmee, his sister-in-law and Boonmee’s nephew Tong. Joining Boonmee’s wife is his son, who comes in the form of a gorilla with glowing red eyes. For all of the possible bizarre, oneiric possibilities that come with the sudden appearance of Boonmee’s wife (who has been dead for twenty years) and son/ape, the scene is not haunting. After the initial shock, it all seems so normal. Surprised, Boonmee quickly becomes enthralled with his loved ones—just as one easily falls back into an old routine, the sudden spectral appearance of his wife and son become not spectacular occasions but important steps to understanding the end of his life.

This is a film of moments and minimal movements. About half way through the movie, lying on his bed, Boonmee hugs the ghost of his wife and proclaims his love for her. What begins as a touching scene soon turns uncanny as the camera lingers on the couple for far too long. It is a frightening scene not because it induces horror, but instead because Weerasethakul plunges deep into the problems of communication. Not only is Boonmee denied an ability to communicate love and passion, but he seems unable to communicate in general. Weerasethakul challenges our own ability to transmit anything in a coherent, understandable way that is truthful to how we feel. There is not a question of whether there is something truthful, but instead a question of how we access that. Boonmee later asks his wife about heaven and hell and if they will be able to meet when he dies. Her reply is simple but devastating: “Ghosts are attached not to places, but people.” Softly spoken the statement emerges from her lips with great beauty and poignancy. Yet we wonder: will she be able to tie herself to Boonmee when he is dead? It is seemingly silly question but it must be asked, are ghosts people?

Tied with such a question is an even greater problem of epistemology. Working through a myriad of genres Boonmee examines not only the problem of knowing others (Boonmee tells his Chewbacca-like son—“I want to recognize you but I can’t”) but more importantly the never-ending quest of self-actualization. Weerasethakul seems to find the answers to such questions in little movements that somehow convey unspeakable greatness. Repeatedly scenes are shown where Boonmee’s sister or wife adjust the tape of Boonmee’s medical apparatus on his stomach. His kidneys slowly deteriorate, and this is the last way to prolong the inevitable. It is a facile action and yet it is the site where the film merges genre tropes with an intensely metaphysical experience.

Through these little movements, Weerasethakul does not merely extol the virtues of life or rely on platitudes about experience, but instead illuminates the sheer importance of the everyday, of our small quotidian actions. Boonmee’s past emerges in the return of his dead wife and prodigal son, but also in small moments such as his lamentation that perhaps his sickness is a karmic consequence of his actions during the war. It is a passing thought for Boonmee, but it is a painful one that seems to weigh heavily. Memory is not a sepia-toned nostalgized vision of the past. For Boonmee, memory is a fragmentary series of events, interactions and relationships, which deny rationality. Logical thought has no place to go.

Many have derided Boonmee as being slow and hard to watch. Such a condemnation seems unnecessary in part because Boonmee is a series of intensely spiritual, albeit contained stories; one could enter the film at almost any moment. Certainly the film’s transcendental world is best experienced in its entirety, but it seems that watching the film and letting one’s mind wander is part of the film’s beauty. Boonmee features a fable like structure that meanders and slithers along. Eschewing a focus on symbolic meaning, Weerasethakul feels his way through a maze of questions. With each act and question characters become imbued with mythic meaning. Embedded in the merging of the ascetic with the extravagant is a question of how people construct a certain mythos to helps interpret the world.

Typically positive characterizations for contemporary cinema come in the form of pithy exclamations; a film is said to “command attention.” Boonmee exists outside of such a lexical understanding—this is not a film that forces anything on the viewer. Like Antonioni’s L’Aventura, Boonmee does not dash towards a final goal but instead lurches forward, peeking behind various bushes, revealing more every minute, all the while the film’s feet remain firmly entrenched in the earth. Boonmee exists in a realm that is both deeply depressing yet emotionally enlightening. Weerasethakul opens up not just a visual or aural landscape, but an imaginative world. The film’s ultimate triumph is not that it helps us understand cinema but that it helps us understand the very world outside of the theater.

-Nicholas Forster

Uncle Boonmee Who Can Recall His Past Lives played At the MFA from April 6-9 and will be opening in Boston again in coming weeks.

The film won the Palme d’Or in 2010.

Written and directed by Apichatpong Weerasethakul; directors of photography, Sayombhu Mukdeeprom, Yukontorn Mingmongkon and Charin Pengpanich; edited by Lee Chatametikool; production design by Akekarat Homlaor; produced by Simon Field, Keith Griffiths, Charles de Meaux and Mr. Weerasethakul; released by Strand Releasing.

With: Thanapat Saisaymar (Boonmee), Jenjira Pongpas (Jen), Sakda Kaewbuadee (Tong)