Normally you don’t see flying and fish in the same phrase. How can an animal that spends all of its time in the water have the ability to fly? There are even species of birds that don’t have the gift of flight (sorry, penguins), so how can fish fly? In fact, scientists have discovered over 60 species of fish that can take the skies.

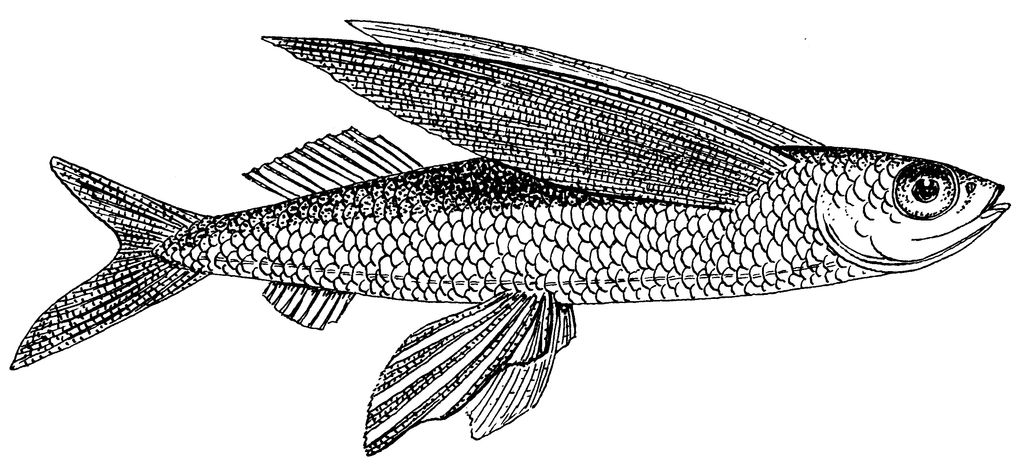

So how do they do it? Well, first off, fish technically don’t have any wings to flap, so they actually glide. In order to get into the air, they swing their tails rapidly from side to side and propel themselves out of the water. Once they’re airborne, the fish spread their long pectoral fins and their shorter pelvic fins and tilt them upwards. These outstretched fins are analogous to wings on a plane, so lift is created in the same way. As the fish glides descends slowly over the water, it slaps the surface with its tail in order to keep on gliding.

This doesn’t sound like the most efficient flying, but it really does work for fish. They have been observed gliding for over 40 seconds; they can travel hundreds of feet through the air just by gliding and can motor at a speed of up to 40 miles per hour. Below is a video of a 45-second “flight” of a flying fish, shot by a Japanese crew member.

Initially, four-winged fish didn’t exist. Scientists believe that four-winged fish evolved from two-winged fish, developing larger pectoral fins that would aid in gliding. Having an extra set of pelvic wings helps fish travel larger distances, and enables them to turn and and change the altitude of their flight, as two-winged fish can only fly in shorter distances of straight paths. These wings evolved as a result of predation. Fish use gliding as a defense mechanism to escape from predators such as sharks and seabirds.

Initially, four-winged fish didn’t exist. Scientists believe that four-winged fish evolved from two-winged fish, developing larger pectoral fins that would aid in gliding. Having an extra set of pelvic wings helps fish travel larger distances, and enables them to turn and and change the altitude of their flight, as two-winged fish can only fly in shorter distances of straight paths. These wings evolved as a result of predation. Fish use gliding as a defense mechanism to escape from predators such as sharks and seabirds.

Scientists have now found that studying flying fish could actually help make aircraft more efficient. In fact, research has shown that fish are just as effective as gliding as some birds, with a lift-to-drag ration of 4.4. Dr. Haecheon Choi, a mechanical engineer at Seoul Nation university in South Korea, explains that the extra set of pelvic wings help create a flow of air that accelerates towards the tail of the fish, helping to create additional lift.

All in all, studying flying fish could help engineers create and improve the aerodynamics of aircrafts. Features from the gliding of fish could be incorporated into human-powered flight and make it more efficient. Because if fish can do it, why can’t we?

Citations:

One Comment

Lorena Barba posted on October 7, 2012 at 12:39 pm

When quoting the lift-to-drag ratio of the flying fish, it is helpful to compare it with other gliding creatures.

A flying squirrel has an L/D of about 2, and for the house sparrow, it is about 4.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lift-to-drag_ratio

So, it looks like some flying fish as as good gliders as sparrows!