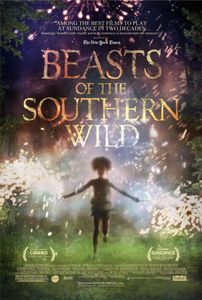

Beasts of the Southern Wild remains a critical darling thanks in no small part to its “magical realist” aesthetic and its tough young star, Hushpuppy (Quvenzhané Wallis). But, cultural critic bell hooks sees “No Love in the Wild,” arguing that the “magical” focus of the film deflects attention away from the pornography of violence at its center.[1] Understanding the gulf between these reactions, and what they suggest about the current media landscape, means placing Beasts into the two artistic contexts it draws from—Southern artmaking, (encompassing artists as wide-ranging as Zora Neale Hurston, Eudora Welty, and Charles Burnett) and American mainstream filmmaking. This dual history illuminates the film’s power, problems, and reception. As in Hurston’s Their Eyes Were Watching God, in Beasts, Southern folklore turns subjects who might be marginalized in other texts (African Americans, the rural, the poor) into lyrically rendered protagonists—that lyricism seems a primary drive in positive reactions to the film, who rarely mention the film’s political import. The parallel history of African American exploitation in mainstream American cinema illuminates hooks’s visceral reaction against the violence Hushpuppy experiences and her argument for the film’s lyricism as a political cop-out. Neither camp is able to fully account for the film which so thoroughly mixes the political and the magical. Beasts, then, speaks volumes about current discourses surrounding American filmmaking, the “one step forward, two steps back” dance filmmakers remain locked into when representing non-white characters, in pieces as radically different as Beasts and The Great Gatsby, and one potential way out.

Beasts of the Southern Wild remains a critical darling thanks in no small part to its “magical realist” aesthetic and its tough young star, Hushpuppy (Quvenzhané Wallis). But, cultural critic bell hooks sees “No Love in the Wild,” arguing that the “magical” focus of the film deflects attention away from the pornography of violence at its center.[1] Understanding the gulf between these reactions, and what they suggest about the current media landscape, means placing Beasts into the two artistic contexts it draws from—Southern artmaking, (encompassing artists as wide-ranging as Zora Neale Hurston, Eudora Welty, and Charles Burnett) and American mainstream filmmaking. This dual history illuminates the film’s power, problems, and reception. As in Hurston’s Their Eyes Were Watching God, in Beasts, Southern folklore turns subjects who might be marginalized in other texts (African Americans, the rural, the poor) into lyrically rendered protagonists—that lyricism seems a primary drive in positive reactions to the film, who rarely mention the film’s political import. The parallel history of African American exploitation in mainstream American cinema illuminates hooks’s visceral reaction against the violence Hushpuppy experiences and her argument for the film’s lyricism as a political cop-out. Neither camp is able to fully account for the film which so thoroughly mixes the political and the magical. Beasts, then, speaks volumes about current discourses surrounding American filmmaking, the “one step forward, two steps back” dance filmmakers remain locked into when representing non-white characters, in pieces as radically different as Beasts and The Great Gatsby, and one potential way out.

Beasts does dramatize the social and political violence hooks discusses in the article linked above, particularly through the interactions between Hushpuppy and her father, Wink (Dwight Henry). Wink’s poverty-borne illness does lead to a desperate, mean desire to teach Hushpuppy to take care of herself, “like a man.” Hushpuppy is dressed inappropriately and abused verbally. The bayou—aka the Bathtub—is destroyed by the government’s belated, misguided intervention. Hushpuppy’s resilience in the face of these hardships, as it connects to the capitalistically self-edifying trope of black women’s strength as the solution to the disproportionate socioeconomic obstacles African Americans have historically faced, is troubling. hooks’ critical indignation is not only well-founded in response to the film, but makes even more sense in a world where a female, non-white lead is still revolutionary, and strong black women are often not portrayed in their own right, but as filmic salves/catalysts for other people’s growth (re: The Help). This is the world of viewers who patted themselves on the back for watching Hushpuppy’s story, but left the theater with no plans to help the very real Hushpuppies of the world—the neglected children the film depicts and hooks discusses in her piece.

It is also a world that recently saw The Great Gatsby, a novel that deeply acknowledges the Jazz Age’s debt to African American labor and culture, remade into a film that transforms African Americans to a grotesquerie of entertainment. A saxophone player scores a raucous party of white revelers; black female bodies gyrate for the pleasure of white men; black bourgeoisie men and women drive by narrator Nick Caraway, but are evacuated of the social commentary they provide in the book. These are ironic inclusions meant to highlight the Jazz Age’s simultaneous fetishization and subordination of black art and bodies to white fantasies, as well as the accompanying mainstreaming of African American culture in the Jazz Age to the present day. If this ironic strategy works as it is meant to (which is itself debatable), it is a canny tactic to get at the raced way the American cultural industry shaped itself and, in fact continues to tells its stories. But, as mindful as this strategy can be, it still pushes African Americans back to the edges of the Great American narrative after the very book it adapts brought them to the center: it means that in one of the most hyped films of the year, African Americans are acknowledged as an important “looming presence,” but are denied authentic subjecthood or names.[2] It means that this year, mainstream film viewers have been most often been treated to white fantasies of blackness in place of actual black characters, and it means filmmakers who follow in Baz Luhrmann’s footsteps are destined to repeat the strange dance of showing African Americans without actually showing them.

Here’s the unfair, but totally necessary comparison: in another white-authored piece from last year, a Southern community of rural, poor, black and white Americans got two hours of screen-time to tell their story, and audiences responded. While hooks argues the film’s magical real aesthetic enchanted audiences at the expense of informing them, there is another way to read Beasts. The film’s aesthetic does not deflect attention away from the political or the problematics of the gulf region: it made the vocalization of the larger, messier history of the region possible. This is a history that includes domestic abuse as well as devastatingly lyrical literature—both of which are represented in equal measure in Beasts, and in fact must be represented to be addressed. More importantly, the mythic language of the film allowed a traditionally doubly marginalized population to tell their story on their own terms, in the folkloric style indebted to their region.[3]

Chief among this population is Hushpuppy. She is not tragic, melodramatic, sexualized, or precocious; she is not a sidekick, nor is she comic relief. In short, she is none the stereotypes Hollywood would wish her to be. She is not resilient to facilitate the growth of other characters, she performs a wholly different function. She is a fully-formed, gender-fluid character who exists in her own right, and sees the world in an age-appropriate, animistic way. If the film does not pause to note her complexity, make no mistake that within the current media landscape, Hushpuppy’s presence and accompanying declaration that “In a million years, when kids go to school, they gonna know, once there was a Hushpuppy and she lived with her daddy in the Bathtub,” is a political statement.

The film’s political statement may be limited, and the continuing critical excitement surrounding Beasts may be paradoxical and narrowly-fixed. Viewers may not have walked out changed, with activism on their mind. But then again, that was not this film’s goal, its responsibility, nor something it could achieve. Films don’t create activists, viewers have to do that work. However, good films can let characters speak in their own voices, they can make the impact of social problems felt on a massive scale and inspire action, and they can create alternate universes we can both emulate and critique. Beasts does that. I would hope that the film’s flaws, and the larger cultural blind spots it points to, could be acknowledged as a starting point, or even better, a call to arms. See what moves you. Speak out against what doesn’t—the task of acknowledgement and response is as important for us as it is for bell hooks.

-Sarah Leventer

[1] hooks, bell. “No Love in the Wild.” NewBlackMan (In Exile). Mark Anthony Neal. 05 Sept 2012. Web. 15 May 2013.[2] Colby, Tanner. “Mad Men and Black America.” Slate. 14 March 2012. Web. 4 April 2013.

[3] Most actors in Beasts, including Wink, but not Hushpuppy, are bayou residents and non-professional actors.