Woody Guthrie: American, Radical, Patriot, gathers together the complete Library of Congress recordings in one place for the very first time, including the interviews done by Alan Lomax, the VD demos, and the BPA songs written to help celebrate the power of the Bonneville Power Administration as it powered up the Pacific Northwest. In the 1940s, Guthrie sang songs about Hitler for the war effort and donned a soldier’s uniform. He was a man of the people, singing for them and their causes. He was a “commonist”, celebrating the power of the individual, and, in these recordings, the government as well. All of this makes for a complex character, and a wonderful new set of music, courtesy of Rounder Records.

Woody Guthrie: American, Radical, Patriot, gathers together the complete Library of Congress recordings in one place for the very first time, including the interviews done by Alan Lomax, the VD demos, and the BPA songs written to help celebrate the power of the Bonneville Power Administration as it powered up the Pacific Northwest. In the 1940s, Guthrie sang songs about Hitler for the war effort and donned a soldier’s uniform. He was a man of the people, singing for them and their causes. He was a “commonist”, celebrating the power of the individual, and, in these recordings, the government as well. All of this makes for a complex character, and a wonderful new set of music, courtesy of Rounder Records.

I spoke with Bill Nowlin, co-founder of Rounder Records and producer of the new set. We talked about Guthrie’s position here as he worked for the government, his lasting influence, and what may still remain in the vaults for our future enjoyment.

In your liner notes, you call Woody Guthrie a “commonist”. Can you explain what you mean by that?

It’s kind of a play on words, but it’s his play on words, and not mine. (I wish I could take credit for it!) Some people called him a Communist, but one of his witty rejoinders was to call himself a “commonist” – essentially, someone who was sympathetic to the “common man.”

You start your notes with the sentence, “Woody Guthrie loved his country.” How does his involvement with the government complicate our idea of Woody Guthrie as a political songwriter?

It doesn’t necessarily complicate our idea – but that depends on the person. We all have a tendency to see things through the prism of our own beliefs and mindset. Someone who themselves was an anti-government radical (or at least one highly suspicious of government) might tend to see Woody as one, too. That might leave them with the comfortable feeling that Woody endorsed their views. That person might find it complicating to realize how much Woody wanted to work with or for the government, at least on some matters.

One can still be political as a songwriter, of course, regardless of one’s politics. There’s nothing to prevent a songwriter today from writing a song about how wonderful John Boehner and Mitch McConnell are.

How did Rounder Records first get involved with these recordings?

Rounder first got involved with these recordings back in the 1980s. It was in August 1987 that we released the Columbia River Collection (Rounder 1036) as an LP and CD. Those were the songs Woody recorded for the Bonneville Power Administration, and which are again presented in Woody Guthrie: American Radical Patriot, along with an additional track. We had started on that project around 1985.

In October 1988 that we released the Library of Congress recordings on 3-LP and 3-CD sets. What we released than was the same material which Elektra had first released in 1964, but which had gone out of print (and, of course, never been on CD).

It was more or less around 2010 that we started working on this set – the complete Library of Congress recordings, with the additional two hours of song and spoken word material which was not on either the Elektra or Rounder packages from the 1980s.

What surprised you most while digging through all of these songs and interviews?

Not a lot, really. It was a true pleasure, though, to take the time to hear Woody recount his life to Alan (and Elizabeth) Lomax – just to hear him talk and play the songs in the context of that conversation. It was also nice to hear – for the first time – the radio dramas he recorded for the war effort and in the fight against venereal disease. I can’t say they were a surprise, but they were definitely new to me.

I guess the biggest “surprise” of a sort was to be able to locate and talk on the phone with a survivor of the Reuben James. As best I can tell, Earl Jaeggi is the only remaining survivor, so it was really nice to be able to talk with him, and to learn that he definitely knew Woody’s song.

Alan Lomax could almost rightly be co-credited with this set. Can you talk a little bit about his efforts to document these stories and forms of music in the 1940s and beyond?

This set would never have happened without the foresight and dedication of Alan Lomax. That is true for a lot of other American music as well, and some traditional folk music of a number of other countries that he helped record and preserve. It was Alan’s particular inspiration to record what he called “musical autobiographies” of some outstanding performers of his day – Jelly Roll Morton, Lead Belly, Aunt Molly Jackson, and Woody Guthrie. Had he not done so, the world might not really have heard of a couple of these artists. Alan not only recorded the Library of Congress recordings of Woody but he helped arrange for Woody to get the job writing songs in the Pacific Northwest for the BPA (Bonneville Power Administration). And we know that the Office of War Information songs, and the public health service songs also had his active involvement – he even wrote the script for the “Lonesome Traveler”, for instance.

Following in his father’s footsteps and broadening his work, Alan was a genius at his work and one could easily argue did more for American roots music that any other person, with evident influences to this very day in the second decade of the 21st century.

You’ve released a handful of Guthrie recordings in the past. Why this set, why now?

We’d always thought – since releasing the edited LOC set back in 1988 – of putting out the full Library of Congress recordings. When Nora Guthrie was visiting Rounder, and talked about gathering all of Woody’s “government recordings” into one set, with liner notes discussing this aspect of his work, it was a natural – and in particular for me, a former political science student and professor. Why now? We just got around to it. We had hoped to aim for his 100th birthday in mid-2012, but when we saw that Smithsonian Folkways had a boxed set in the works, we deferred to them and held ours over to this year.

In the set, Jesus sits right alongside Jesse James and Pretty Boy Floyd—can you talk a little bit about Guthrie’s vision of outlaws and those who challenged authority?

I’m not sure I can give the best answer to your question – simply because I haven’t studied it as much. It would be a good subject for someone to research. I have the sense that he romanticized some of the outlaws a bit, though I don’t think that was uncommon at the time, particularly in Oklahoma where there was apparently a little bit of a subculture of “outlawdom” in the hill country in the 1920s and 1930s. Wanting the outlaw to have some noble characteristics wasn’t unique to Woody; we see it in a number of books and films.

And of course there’s the great “Jolly Banker” song—taking aim at the bankers in Oklahoma.

Bankers were certainly easy targets at the time, and maybe (if we include financiers as well) ought to not be as exempt as they appear to be today. With foreclosures in the thousands, many Oklahomans had to leave their homes during the Depression. It’s not surprising that Woody felt strongly on the subject.

The folk tradition was also important to Guthrie, as it was for blues artists in the south and other musicians. Can you talk about the oral tradition of these songs—where Guthrie picked them up, and how they were transformed by future folk artists like Bob Dylan.

I can’t do this nearly as well as others could. In listening to Woody talk with the Lomaxes about the songs he sang – even some that are listed as written by Woody – we hear him talk himself about where he got the songs from. Most of them weren’t from one person or another, or if they were from someone, they were just songs Woody heard and made his own. He definitely picked up songs along the way, and added to them. Later singers have tended more to replicate songs sung by others, rather than simply sing them their own way.

Can you talk a little bit about the VD recordings? What was the impetus for them, and where did these songs go?

They didn’t really go anywhere. They were basically demos, but Woody wasn’t commissioned to sing them. I’d really love to learn just how Bob Dylan learned four of them so early on – 1961 – in his own career, and what fascinated him enough to have recorded four of them in his “Minnesota hotel tapes.”

Do you think it is fair to say that the Dust Bowl helped to create Woody Guthrie as an artist? I’m thinking about how Steinbeck, similarly, must be looked at through the lens of the Great Depression, and how Woody Guthrie seems to be the other towering artist of that era.

Do you think it is fair to say that the Dust Bowl helped to create Woody Guthrie as an artist? I’m thinking about how Steinbeck, similarly, must be looked at through the lens of the Great Depression, and how Woody Guthrie seems to be the other towering artist of that era.

Well, certainly that was where Woody’s muse first matured, dealing in his songs and stories with the Dust Bowl, the displacement, and the migration westward of so many people from his part of the country. Steinbeck, of course, had something to say about Woody – you’ll read that in the notes to this set.

What was the decision process behind putting a 78 in the box set? The physical aspect of an new/old 78 seems like a fascinating choice, given the fact that it might be hard to actually play it.

It just seemed like a good idea. When Woody was first recording, and when all of the tracks on his package were cut, the recorded medium was the 78 rpm record. It was only later that 45s first appeared. And later still that we developed the long-playing 33rpm record, then the cassette, the CD, etc.

An increasing number of people are turning back to vinyl these days, which is an interesting counter-trend (I’m not sure how far it will go). I’m told that today’s record players can handle 78s. But I’d venture a guess that of the 5,000 people who buy this limited edition package, less than a thousand will ever hear the tracks on the 78 by actually playing the 78 itself.

Guthrie material keeps emerging, with his novel House of Earth even finding release earlier this year. What else is out there that we don’t know about?

I guess we’ll find out! Nora Guthrie and her staff now count over 3,000 songs Woody wrote, and most of them have never been recorded by anyone. My guess is that we’ll hear more of those in the next several years.

There is another thematic approach to Woody’s work that I am slowly working on developing, but I’ll keep that under wraps for now.

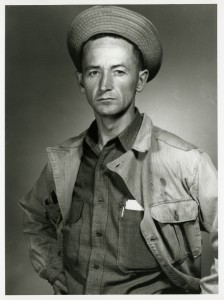

What do you think we can still learn from Woody Guthrie?

He was a straight-forward guy. There was a fundamental honesty about him, and a directness. Those are good traits that will always be exemplary, for all of us. Of course, some of the particular issues he addressed in his songs, and what else he had to say, are no longer current issues, but a surprising number of them still obtain. There will probably always be economic inequality, with those of power and influence using the tools available to them to try to solidify and expand their position of advantage. There will always be room for straight talkers who can stand up and point out inequities and give voice to those who may not find an easy time voicing their own, perhaps even unarticulated, feelings.

Oral histories of the folk tradition are so important to our understanding of America during this time period. Do you think there is room for this type of project today? Do we have anyone like Alan Lomax today? Or Guthrie?

There is a very definitely plenty of room for oral history – not just in folk tradition but in all fields. There are many scholars and other dedicated people working today to document the lives of those who came before, taking advantage of tools available to us today – such as video – which weren’t around at Woody’s time. I don’t know that there’s anyone quite like Alan Lomax or Woody Guthrie today, in America. There could well be in other lands, though I don’t know of any. I don’t know if there really could be anyone quite like Alan Lomax today, because of the proliferation of media and the fact that there are hundreds of people doing documentary work. But maybe there will be in time to come.

Every few years there seems to be a bit of a folk revival. In recent years, bands like the Avett Brothers and Mumford and Sons have gotten a lot of attention—Mumford even contributing to the new Coen brothers film, Inside Llewyn Davis. This is wonderful, of course, but do you think it is a challenge for contemporary audiences to reach back eighty years to dig a little deeper into the folk tradition?

Periodic return to the essential simplicity of acoustic, “hand-made” music is probably something that will continue. Many of today’s “folk-style” musicians themselves do look back to Woody Guthrie, and others. See, for instance, the New Multitudes project that Rounder released a couple of years ago. For younger audiences today, that music seemed to resonate. Whether contemporary audiences themselves will do some digging, I don’t know. I’d like to hope so.