One unarmed black man strangled, a second unarmed black man shot. These recent horrible events have forced most Americans to become momentarily aware of the powerful relationship between the law, law enforcement and identity. Community leaders and national newspapers are calling for reduced enforcement of low-level crimes – a reversal of the “broken-windows” police policy that linked petty crime as a pre-cursor for the development of larger social ills. The relaxing of enforcement follows other recent moves to shift the borders of inclusion and exclusion. President Clinton stopped enforcing the ban on gays in the military and President Obama stopped enforcing the ban on gays marrying and the use of marijuana. These inactions demonstrate that in the United States, the enforcement of the law is inconsistent. Selective enforcement of the law has historically preceded cultural change as different groups negotiated the power relationships intertwined with law and culture.

One unarmed black man strangled, a second unarmed black man shot. These recent horrible events have forced most Americans to become momentarily aware of the powerful relationship between the law, law enforcement and identity. Community leaders and national newspapers are calling for reduced enforcement of low-level crimes – a reversal of the “broken-windows” police policy that linked petty crime as a pre-cursor for the development of larger social ills. The relaxing of enforcement follows other recent moves to shift the borders of inclusion and exclusion. President Clinton stopped enforcing the ban on gays in the military and President Obama stopped enforcing the ban on gays marrying and the use of marijuana. These inactions demonstrate that in the United States, the enforcement of the law is inconsistent. Selective enforcement of the law has historically preceded cultural change as different groups negotiated the power relationships intertwined with law and culture.

This discussion highlights ways in which the law has been, and can be used as a rich resource for the historical study of continuity and change in American culture.

Response: Will Edmonstone

Race and the Social Security Act of 1935

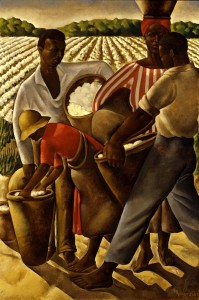

Smithsonian American Art Museum

In examining the relationship between law and the politics of identity, it is important to remember that while some laws are unjust “on their face,” such as the recently overturned Defense of Marriage Act, others are unjust only as they are applied. In other words, while an examination of law and identity often leads to a discussion about explicit or deliberate exclusion, we should be careful not to overlook the ways in which exclusion in U.S. legislative history can often take on more subtle forms. These indirect forms of exclusion often covertly perpetuate structural inequalities. Take for example, the 1935 Social Security Act, which excluded nearly half of U.S. workers from coverage.[1] Among the excluded groups were agricultural and domestic workers, which included large segments of the African American workforce.[2] Understanding exactly how race functioned in the construction of the Act is a complex task, but doing so highlights the ways in which law-making can both reflect and build upon already existing prejudice without expressing deliberate racist intent in an explicit sense.

In his survey of the historiography of this exclusion, Larry DeWitt, a public historian with the Social Security Administration, has argued that scholars have been too quick to explain the exclusion of farm and domestic workers as a function of racism. Dewitt challenges the argument that Southern law-makers “deliberately” excluded African Americans from the Act out of fear that Social Security coverage would bolster their independence as workers. DeWitt posits that such claims are “conceptually flawed and unsupported by the existing empirical evidence.”[3] He argues instead, “It is more in keeping with the evidence of the record to conclude that the members of Congress (of both parties and all regions) supported these exclusions because they saw an opportunity to lessen the political risks to themselves by not imposing new taxes on their constituents.”[4] While DeWitt’s argument convincingly complicates notions of “intentional” racial exclusion, his argument does not adequately address the more complex ways in which racial ideology functioned during the construction of Social Security. As Mary Poole has argued, “The Act’s framers…did not design policy to deliberately discriminate against African Americans, but they structured the Social Security Act in such a way that it would inevitably discriminate against some Americans.”[5] She goes on, “Once the line was drawn and the atmosphere of scarcity established, a scramble ensued…With no protections built into the Act, and no group of policymakers willing to lay down and die for them, the existing marginality of the country’s 12 million African Americans guaranteed that they would fare worst in the scramble.”[6] Thus, while the Social Security Act did not contain a racial animus “on its face,” the law nevertheless reinforced racial inequality as it was applied. The subtlety of this distinction may make it appear unimportant, but it offers some insight into the legality of indirectly state-sponsored racism.

[1] DeWitt, Larry. “The Decision to Exclude Agricultural and Domestic Workers from the 1935 Social Security Act” Social Security Bulletin. 2010, Vol. 70 Issue 4, p49-68. 20p. 1 Chart. 49

[2] Poole, Mary. The Segregated Origins of Social Security: African Americans and the Welfare State. Chapel Hill: North Carolina U.P., 2006. 36-39

[3] DeWitt, 49

[4] DeWitt, 64

[5] Poole, 174 (Poole’s italics)

[6] Poole, 174

This update highlights the importance of reviewing the recently revised employer policies for OCI and off-campus recruiting, effective May 16, 2019. Employers are encouraged to ensure compliance and reach out to the CDO for any clarifications

cat language translator app