Dmitri Shostakovich and

The Struggle For Artistic Integrity Under Stalin

The Struggle For Artistic Integrity Under Stalin

Created By Ben Gagne-Maynard Spring 2013

If they cut off both hands, I will compose music anyway holding the pen in my teeth-

Dimitri Shostakovich, letter to Isaac Glikman, 1936

Introduction:

On the evening of June 28th, 1936, Dmitri Shostakovich reluctantly chose to attended the Bolshoi Theater production of his new and critically acclaimed opera, Lady Macbeth of the Mtsensk District. The opera, a tale of a lonely woman driven to murder by the pains of unrequited love and tsarist repression, had been critically well received prior to the performance, heralded by the press as a triumph of Soviet culture and tradition. Yet to the composer’s surprise, General Secretary Joseph Stalin and the entire Politburo were also in attendance at the Bolshoi premier, visibly mocking and criticizing the piece with marked dissaproval. Two days later, the soviet newspaper Pravda had denounced his work as “coarse, primitive and vulgar,” all but ruining his artistic and social livelihood. Shostakovich, once the undeniable symbol of proletarian symphonic music and artistic celebrity in the Soviet Union, had been reduced to a symbol of cultural formalism and abstraction, at odds with the artistic patriotism and realism of the day.

My attempt to research and study Shostakovich and his artisitic life from the period of 1927-1975 exposed a great challenge I encountered in the study of Soviet cultural history, in that explicit expressions of thoughts, emotions, and dissent are hard to find. Primary, Secondary and critical sources on Shostakovich’s musical and cultural impact are clouded with a veil of uncertainity, as it is clear that under the threat of repression and execution intellectual freedom and artistic integrity were restrained and clear statements of opinion are rare. Much of what now exists of Shostakovich’s correspondances with friends and colleagues is rife with irony, contradiction, satire and ambiguity. Like his music, Shostakovich’s writings and letters, and memoirs have been constantly reevaluated for their relevancy, sense of irony, meaning and personality. The current debate surrounding Shostakovich revolves around his memoirs, compiled by writer Solomon Volkov under the title of Testimony, and his lengthy correspondances with his close friend, Isaak Glikman. Their underlying sense of anti-communism and dissidence has been a constant source of debate among histiographers and critics, as how to portray Shostakovich’s relationship with communism and Stalin in particular is a source of constant argument. The goal of this guided history is to peice together the primary sources available to us regarding Shostakovich’s past, consider critical analyses of his life for differing as well as complimentary viewpoints and to place his music itself in the historical and cultural context of his time in order to find some sort of understanding of Shostakovich’s deep internal struggle for artistic integrity in a country of ruthless artistic conformity and repression. If we may understand Shostakovich’s relationship with communism and his music, perhaps a more enlightened view of the cultural climate of the Soviet Union under Stalin might be found. Shostakovich’s story and the primary, musical and secondary sources listed below may provide insight into how culture and art under the Stalinist regime struggled to uphold its integrity without suffering the consequences of repression. By constructing this guide for research, I hope to provide a base of information and sources that help to piece together Shostakovich’s amazingly complex story from all sides of criticism and interpretation, with the hope that such a scale of information might encapsulate the scope of his incredible impact on Soviet culture and history and reveal even the most subtle of his attempts to speak his mind.

Secondary Sources

I began my research by studying secondary biographical sources that have been generally considered as authoritative books on the subject of Shostakovich, his music, his relationship with fellow musicians, his relationship with Stalin and proletarian art and music as a whole. I chose to do this becasue in order to better understand the primary sources and historical context in which they might be placed, I felt some degree of biography and historical analysis of Shostakovich’s life and music must be considered first. As I was new to the study of Shostakovich himself but am relatively familiar with his music, I decided it would only be fitting to start from the most widely read and studied of secondary material as a base of furthur research and understanding of his much debated and misunderstood artisitic life.

Postage Stamp of Shostakovich, commemorating his death in 1975

Biographical Sources

Solomon Volkov, Shostakovich and Stalin (New York: Alfred A Knopf, 2004) Print.

This book was instrumental in my early research, as it provides an extensive and rather objective guide to the political struggles that Shostakovich faced as a composer, beginning with a chronicle of his early success as a “Proletarian” composer and his reaction to his early denouncement in 1936, marking the beginning of a greater artistic purge implemented by the Soviet government from 1936-1939. Volkov’s depiction of Shostakovich’s troubled relationship with the Soviet government and Stalin in particular places Shostakovich’s struggles with expression versus conformity in a historical context of the great cultural purges of the 1930’s, yet also suggests that Shostakovich’s personal character influenced the volatility of his relationship with Stalin. The section on Shostakovich’s “War Symphonies” and his second denounciation are incredibly informative, and the book in general is a great depiction of the political ironies behind Shostakovich’s musical works and his correspondances with fellow musicians and friends. Though the book is subjective in its arguments surrounding Shostakovich’s memoirs and letters, mabye because Volkov himself edited the memoirs, it is a good basis for furthur research of primary sources relating to the topic of the book.

Stalin in 1936

Elizabeth Wilson , Shostakovich: A Life Remembered (Princeton, N.J. : Princeton University Press, 1994) Print.

A more gradual and detail based biographical source compared to Volkov’s, Wilson’s book is a very anecdotal depiction of Shostakovich’s life. Relying on more historical fact and primary source analysis than analysis of historical context and expository argument, the book provides many anecdotes and storys which display Shostakovich’s troubled relationship with his country , and his even more conflicted relationship with music. The source provides a good basis for adding biographical fact to a research paper, yet does not supplant primary texts for their historical relevance.

Secondary Musical Texts

Shostakovich’s ultimate expression of emotion and political opinion may be seen in his artistic medium, and a number of secondary sources are indispensible tools for research. Critical analysis of Shostakovich’s symphonies, operas, sonatas and quartets all illumnaites the dark ironies and emotions that underscore their forms, and many sources I discovered provide musical analysis that relies heavily on historical context to describe the motives and emotions behind the composer’s music, and are useful branching-off points for putting the composers music into the greater context of his time.

David Edwin Haas, Leningrad’s Modernists: Studies in Composition and Musical Thought, 1917-1932 (New York: Peter Lang, 1998) Print.

Haas introduces Shostakovich in a non-exclusive manner in this source, as the title makes clear. Yet his placement of Shostakovich in the context of the greater Russian Classical Music circle of Leningrad in the early 1920’s is important, as both musical analysis and the historical context of Shostakovich’s works provides important insight into the greater trend of guarded artistic expression that was present in the early Soviet union.

Wendy Lesser, Music for Silenced Voices: Shostakovich and his Fifteen Quartets (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2011) Print.

This source provides perhaps the most informative and expository argument focusing on Shostakovich’s music as a focus in my entire research. Lesser focuses on an often overlooked set of compositions, Shostakovich’s string quartets, and provides insight into their sense of pain, emotion, passion and irony and how their musical qualities might represent a greater sense of emotion Shostakovich attempted to release on behalf of the people. The introduction of the book is especially helpful to my arguemnt, because it is less technical in its analysis of Shostakovich’s music and more ideological, placing emphasis on their emotion and tonal qualities rather than their musical technicalities and form.

Shostakovich at the Piano, Circa 1941

Electronic and Multimedia Sources

After my research took me to more secondary analysis of Shostakovich’s life, historical context and music, a number of valuable electronic and multimedia resources presented themselves to me. Before I could move into finally examining Shostakovich’s life and relationship with his own artistic integrity, I felt it was instrumental to in fact listen and dissect his music, discover criticism of his letters and music on a more collective scale through electronic databases, and to furthur try to understand Shostakovich’s troubled past through articles of critical and historical argument.

Musical sources

The Seventh Symphony, more commonly known as the “War Symphony” or “Leningrad Symphony,” is considered by many critics, including some sourced elsewhere in this reseacrh guide, to be Shostakovich’s most emotional and powerful piece. The symphony is an artistic response to the horrors of the seige of Leningrad during WWII and the intense emotional toll the seige, and the war itself, took on the Soviet people. It has generated a good amount of controversy, because the intent of the symphony is often confused because Shostakovich’s own opinion on Stalin’s approach to the war and the emotional character of sadness rather than triumph in the piece hints at a tragic, highly critical and less ideolized depiction of the war, one that might have appealed to the more repressed feelings of the Soviet public.

The Fifth Symphony, also heralded as deeply emotional and personal to Shostakovich and the greater Soviet public, is a more scathing and bombastic piece of music compared to the 7th Symphony. Whereas both pieces are full of emotional character and feelings of tragedy, the fifth also plays into the more passionate Soviet realism of the time period in which it was written, in the midst of the great purges of 1937. The symphony has generated a great deal of controversy, as it can either be seen as a genuine piece of Soviet realism, as it was wildly popular among the Soviet elite at the time, or a piece of ironic charcter attempting to appeal to the great tragedy of Stalin’s purges and their emotional footprint on the lives of the Soviet people. The particular recording here, made in 1959 of Leonard Bernstein conducting the New York Philharmonic, was made with Shostakovich himself in attendance, and is an excellent interpretation of the piece’s raw emotion and sinister character.

Databases and archives

A number of databases specifically focusing on Shostakovich presented themselves to me as my research continued. They proved vital to my argument, in that they contained such a wealth of critical information, primary source material, subject matter and furthur ideas for research. They served as a gateway into finally finding some way of interpreting the primary sources I researched in a balanced and well informed way, and provided alot of commentary on those sources as well.

This link is to a database compiled by the Southern Illinois University at Edwardsville, entitled “Shostakovichiana.” This database is essentially a collection of critical sources, analyses of primary and secondary sources, chronological tools, links to book reviews and modern interpretations of Shostakovichs life, and furthur pages of research. I found the section on Shostakovich’s letters to Isaak Glikman and their critical response from Ian Mcdonald to be particularly useful, as it provided me with furthur insight into the differing arguments surrounding the nature of Shostakovich’s writing and tone in dealing with his true opinions. Also, the databases link to several testimonies of Shostakovich’s attitude toward the Soviet regime provided me with primary spurces I would have otherwsie not enocuntered at all. Though not all the information on the site is useful and relevant, I found that in general this database was highly beneficial to my argument.

This site, a small database dedicated to Shostakovich’s works and their historical context, had mostly redundant and useless items for me in terms of my research. However, it did provide a rather useful section on the historical context of Shostakovich’s Fifth symphony, quoting major publications on Shostakovich and providing detailed information as to how one might listen to the Fifth Symphony in a more historically enlightened manner.

The BU library system actually had a startling amount of information on Shostakovich, including many of his scores and notes to those scores. The site proved useful in gathering a basic group of research guides and texts, and the JSTOR database connected with the site had a number of articles that proved useful to my research.

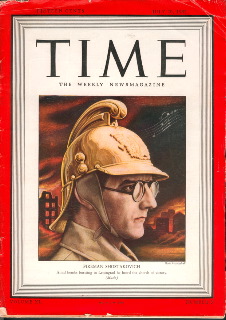

Shostakovich as a volunteer fireman, cover of Time Magazine, July 20, 1942

Articles

My research led me to a number of articles concerning Shostakovich, some more relevant and applicable than others. By researching using the BU library database, I found a number of articles that concerned a part of my topic I had either begun to slowly understand and contextualize or that had not yet been considered for addition to a possible paper.

Pauline Fairclough, “The ‘Perestroika’ of Soviet Symphonism: Shostakovich in 1935” Music & Letters, 2002, Vol.83(2), pp.259-273 [Peer Reviewed Journal]

This article provided alot of insightful information as to how Shostakovich’s musical and personal character were symbols of artistic integrity and bravery in a time of repression and cultural uniformity. The article is well written and will be easily quotable when the time comes that more expository evidence is needed to solidify my argument.

Richard Taruskin, ” The Peculiar Martyrdom of Dmitri Shostakovich-The Opera and the Dictator” New Republic, 1989, Vol.200(12), pp.34-40

This article coincides with a close historical analysis of the period between 1935-1937 when Stalinist policies towards art and culture began to tighten their grip and scope of what was truly “Soviet” that Solomon Volkov provides in his book “Shostakovich and Stalin,” yet provides a more anecdotal and detailed depiction of the relationship they actually had when Shostakovich’s Lady Macbeth of the Mtsensk District was premiered. This article is a good source of possible quotations and shows just how contentious the debate over Shostakovich’s relationship with the USSR’s political elite really is, even 40 years after his death.

Shostakovich in Frankfurt, Germany in 1949, shown seated under an ‘Operations Vittles” advertisement. ‘Operation Vittles’ was the allied attempt to deliver food and supply goods to Berlin despite the Soviet blockade there.

Primary Sources

Choosing to study secondary texts on Shostakovich first and listening to his music under its historical context, in consideration of the life and times of their composer, provided me with a strong base for understanding the complexity of the primary sources surrounding his story. Because repression, censorship and violent suppression of dissent were basically institutionalized in the Soviet Union during Shostakovich’s lifetime, the composer’s correspondances with friends and family have ironic and ambiguous undertones, as it is unclear whether the political zeal which Shostakovich displays in his letters is a sincere affirmation of his political ideals or a poignant and scathing depiction of the absurdity and brutality of the Stalinist regime. The memoirs of Shostakovich, compiled by Solomon Volkov under the title “Testimony” furthur complicate the situation, as they appear to clearly show Shostakovich’s discontent with the government and Stalinist policies. Yet it is unclear whether Shostakovich even wrote the memoirs, adding confusion to an already complex situation. But because of my readings of various different viewpoints on the subject of Shostakovich’s life, music and personal writings, I feel I was able to look at the primary sources listed below in a far more objective light, considering differing viewpoints on their tone and accuracy in order to form a well rounded opinion for myself.

Dmitri Dmitrievich Shostakovich, Testimony: The Memoirs of Dmitri Shostakovich, edited by Solomon Volkov (New York : Limelight Editions , 2004) Print.

The memoirs are perhaps the most important and most controversial of Shostakovich’s primary texts, as today it is hotly debated as to whether he even wrote them at all. Reportedly compiled after being dictated to Solomon Volkov, they represent Shostakovich’s more personal and emotional reflections upon his life and music, and are much more explicitly anti-stalinist and dissentful than other primary sources appear. The memoirs, despite their controversial nature, provide incredibly useful quotatio and insight into what Shostakovich possibly thought about all that had occured in his musical and personal life, revolving around the assumption that his true emotions and artistic ambitions had been squandered by Stalin’s regime yet kept alive by some guarded form of hope. The memoirs provide a powerful base of primary quotations for research, and are important when placed in comparison with other primary texts.

Dmitri Dmitrievich Shostakovich, Story of a Friendship: The Letters of Dmitri Shostakovich to Isaak Glikman 1941-1975, compiled by Isaak Glikman (Ithaca, N.Y. : Cornell University Press , 2001) Print.

Shostakovich’s lengthy and seemingly countless letters to his close friend, Isaak Glikman, are catlogued chronologically in this sourcebook, and provide insight into the nature of Shostakovich’s relationship to his political and artistic world. the letters have been greatly debated, as their tone may be interpreted as either incredibly sincere and straightformward, or scathingly ironic and mocking of Soviet dogmatism and self-assurance. Coupled with my earlier extensive reading of criticism and analysis of the letters tone and meanings, the letters themselves both illuminate the complexity of Shostakovich’s situation as an artist struggling for ideological and musical integrity and highlight just how little is known for sure about Shostakovich’s true opinions. However, if read in historical context and with a degree of objectivity, the letters provide a great degree of useful information and possible evidence to support my fast developing argument.

This link is to an electronic copy of the January 28th, 1936 publication of a scathing denounciation of Shostakovich’s music in Pravda magazine, an article entitled “Muddle instead of Music.” This primary source is an indispensible source of information for my research topic, as it directly shows how the impact of Shostakovich’s original and avante garde music affected his political and social standing among the Soviet public. The article is a direct response to Shostakovich’s Lady Macbeth of the Mtsensk District and exhibits a fine example of a greater trend in Soviet cultural history, the denounciation of symbols of artistic ingenuity and integrity as a means to supress cultural dissent and ideolize Soviet music and art. The article is an incredibly useful tool as a primary source for my research guide, and is a telling depiction of the struggles which Shostakovich faced as an artist struggling between artistic integrity and political exile.