Introduction

MR. STRIPLING: Mr. Gerhart Eisler, take the stand.

MR. EISLER: I am not going to take the stand.

MR. STRIPLING: Do you have counsel with you?

MR. EISLER: Yes.

MR. STRIPLING: I suggest that the witness be permitted counsel.

THE CHAIRMAN: Mr. Eisler, will you raise your right hand?

MR. EISLER: No. Before I take the oath-

MR. STRIPLING: Mr. Chairman-

MR. EISLER: I have the floor now.

MR. STRIPLING: I think, Mr. Chairman, you should make your preliminary remarks at this time, before Mr. Eisler makes any statement.

THE CHAIRMAN: Sit down, Mr. Eisler.

-Gerhart Eisler, brother of composer Hanns Eisler, before the House Committee on Un-American Activities, February 6, 1947

After the Second World War, as tensions began to simmer between both the United States and Soviet Union and the Hollywood studios and unions like the Screen Writers Guild, the House Committee on Un-American Activities turned its eyes towards the entertainment industry, suspecting communist infiltration and propaganda. In October 1947, HUAC opened hearings on the matter, interviewing writers, directors, actors, executives and others in order to find evidence of communist subversion. Most famous among these individuals were ten who refused to confirm their involvement in the Communist Party. The Hollywood Ten, as they became known, were cited for contempt of Congress and served prison time. Others suspected of communist sympathies were denied work by the studios, forcing them to work under fronts or pseudonyms. Others, whether for political reasons or out of reluctance to lose their jobs, cooperated, naming more individuals for HUAC to question.

The purpose of this guide is, for one, to provide a comprehensive database of primary accounts of the blacklist period specifically within the motion picture industry (c. 1947-1960), from autobiographies to interviews to transcripts of the hearings and more, in order to construct a more complex compilatory narrative of the events. The guide also contains context/overview sources, secondary analysis and modern depictions/remembrances of the blacklist period. Hopefully, in using this guide, one might gain a sense of all facets – political, moral, social – of this complicated and confounding period of American history.

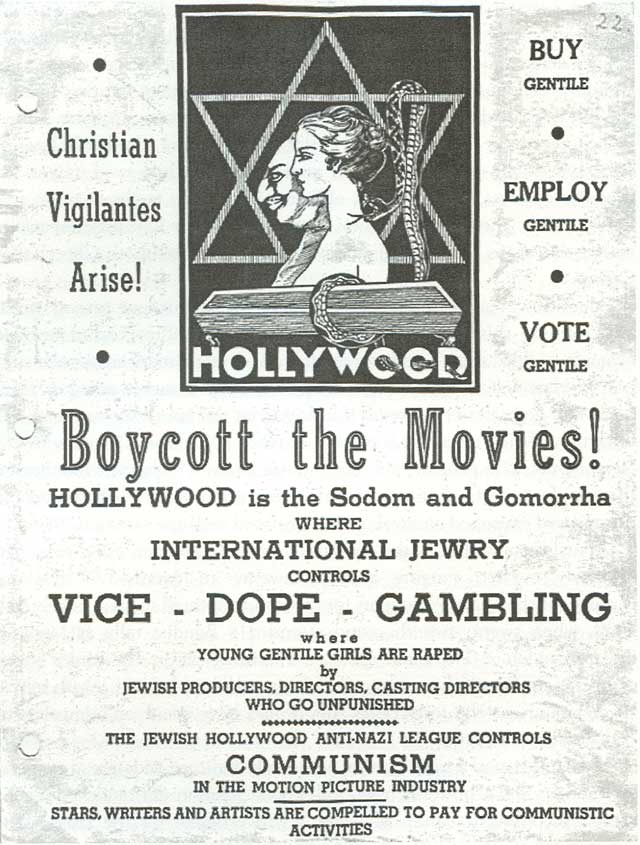

- A 1930’s leaflet from Los Angeles condemns the “International Jewry of fostering “communism in the motion picture industry.” (Jewish Federation Council of Greater Los Angeles Community Relations Committee Collection)

The Hollywood Blacklist

Context Sources

MR. STRIPLING: Are you now or have you ever been a member of the Communist Party, Mr. Dmytryk?

MR. DMYTRYK: Well, Mr. Stripling, I think that there is a question of constitutional rights involved here. I don’t believe that you have-

THE CHAIRMAN: When did you learn about the Constitution? Tell me when you learned about the Constitution?

MR. DMYTRYK: I will be glad to answer that question, Mr. Chairman. I first learned about the Constitution in high school and again-

MR. McDOWELL: Let’s have the answer to the other question.

MR. DMYTRYK: I was asked when I learned about the Constitution.

MR. STRIPLING: I believe the first question, Mr. Dmytryk, was: Are you now, or have you ever been, a member of the Communist Party?

MR. DMYTRYK: All right, gentlemen, if you will keep your questions simple, and one at a time, I will be glad to answer.

MR. STRIPLING: That is very simple.

MR. DMYTRYK: The Chairman asked me another question.

THE CHAIRMAN: Never mind my question. I will withdraw the question.

-Director Edward Dmytryk before the House Committee on Un-American Activities, October 29, 1947

The Inquisition in Hollywood: Politics in the Film Community, 1930-1960

Larry Ceplair and Steven Englund, 1980

The Inquisition in Hollywood provides an sturdy introduction to the blacklist period in Hollywood, beginning with an exploration of left-leaning organizations like the Screen Writers Guild in the 1930’s. Ceplair and Englund go on to construct a digestible narrative surrounding the HUAC hearings and the Ten’s citations, although at times push too far into dramatization and themes of oppression. The book works well in conjunction with other, more objectively written sources.

Ceplair, Larry, and Steven Englund. The Inquisition in Hollywood : Politics in the Film Community, 1930-1960. 1st ed. Garden City, NY: Anchor Press/Doubleday, 1980.

Hide in Plain Sight: The Hollywood Blacklistees in Film and Television, 1950-2002

Paul Buhle and Dave Wagner, 2005

This book answers the very important question of what exactly blacklisted writers, producers and others did once studios began to deny them work.

Buhle, Paul, and Dave Wagner. Hide in Plain Sight : The Hollywood Blacklistees in Film and Television, 1950-2002. Gordonsville, VA, USA: Palgrave Macmillan, 2005.

- The Hollywood Ten, Nov. 1947: (Front, L-R) writer and director Herbert Biberman, attorneys Martin Popper and Robert W. Kenny, writer Albert Maltz, writer Lester Cole; (Middle, L-R) writer Dalton Trumbo, writer John Howard Lawson, writer Alvah Bessie, writer Samuel Ornitz; (Back, L-R) writer Ring Lardner, Jr., director Edward Dmytryk, producer and writer Adrian Scott.

‘A Good Business Proposition’: Dalton Trumbo, ‘Spartacus’, and the End of the Blacklist

Jeffrey P. Smith, 1989

Smith picks up where Ceplair and Englund trail off, which the eventual disintegration of the blacklist. The essay is also a solid background source, arguing that the revelation that Dalton Trumbo had managed to pen Spartacus and many other popular films from inside the blacklist suggested that its end was not far off.

Smith, Jeffrey P. “Hollywood Institutions: ‘A Good Business Proposition’: Dalton Trumbo, ‘Spartacus’, and the End of the Blacklist.” The Velvet Light Trap – A Critical Journal of Film and Television 23 (Spring 1989): 75.

Hollywood’s Cold War

Tony Shaw, 2007

Shaw pulls his historiographical lens back further than other texts on the topic, examining Hollywood’s treatment of Communist themes during the Bolshevik Revolution, up to World War II and through the Cold War. Though extensive, it suggests a much more variable relationship with the Left than books focusing just on the blacklist period.

Shaw, Tony,. Hollywood’s Cold War. Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 2007.

Thirty Years of Treason: Excerpts from Hearings before the House Committee on Un-American Activities

Edited by Eric Bentley, 1971

Though by no means comprehensive, Bentley’s compilation of HUAC hearing transcripts fills in its own gaps with relevant primary documents. These supplementary legal statements, letters, journals and others make conclusions easier to draw, however the compilation as a whole tends to favor the witnesses with noticeable emphasis on the hearings’ negative effects on witnesses and their families and careers.

Bentley, Eric, ed. Thirty Years of Treason: Excerpts from Hearings before the House Committee on Un-American Activities, 1938-1968. New York: The Viking Press, 1971.

Hearings Regarding the Communist Infiltration of the Motion Picture Industry

U.S. Congress House Committee on Un-American Activities, 1947

This is the complete transcript of HUAC’s hearings on Communist influence in Hollywood, available through the Internet Archive. Unlike Bentley’s book, this database contains every hearing conducted between October 20 and October 30, 1947, without any editing or supplementation: a completely objective account of the hearings themselves.

United States Congress House Committee on Un-American Activities. Hearings Regarding the Communist Infiltration of the Motion Picture Industry. Hearings before the Committee on Un-American Activities, House of Representatives, Eightieth Congress, First Session. Public Law 601 (section 121, Subsection Q (2)). Washington, U.S. Govt. Print. Off., 1947.

Primary Perspectives

Additional Dialogue; Letters of Dalton Trumbo, 1942-1962

Dalton Trumbo, 1970

Before his citation and sentencing with the rest of the Hollywood Ten, Dalton Trumbo was one of the industry’s highest paid writers, working on films like Kitty Foyle (1940) and Thirty Seconds Over Tokyo (1944). After, Trumbo continued to work under front credits and pseudonyms. This compilation of letters written by Trumbo gives a useful account of the blacklist period as it was occurring, a benefit not seen in other first-person writings written after the fact.

Trumbo, Dalton,. Additional Dialogue; Letters of Dalton Trumbo, 1942-1962. New York: M. Evans; Distributed in Association with Lippincott, 1970.

Screenwriter Dalton Trumbo, October 28, 1947

(Dalton Trumbo HUAC Testimony Excerpt, 1947. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=tFR4RIyekis.)

Hollywood Red: The Autobiography of Lester Cole

Lester Cole, 1981

Cole’s autobiography, given its many uncomfortable pointed attacks on contemporaries like Dalton Trumbo and On the Waterfront writer Budd Schulberg, dispels any myths of unity or consensus among the blacklisted.

Cole, Lester,. Hollywood Red : The Autobiography of Lester Cole. Palo Alto, Calif.: Ramparts Press, 1981.

Odd Man Out: A Memoir of the Hollywood Ten

Edward Dmytryk, 1996

Dmytryk’s position as the only member of the original Ten to then cooperate with HUAC gives him a unique perspective to share. Compared to his earlier memoir, It’s a Hell of a Life, But Not a Bad Living (New York, Times Books, 1978), Odd Man Out shows Dmytryk to stand firmly by his decision to name names.

Dmytryk, Edward. Odd Man Out : A Memoir of the Hollywood Ten. Carbondale, IL: Southern Illinois University Press, 1996

Wanderer

Sterling Hayden, 1963

Unlike Dmytryk, Hayden, another “cooperative witness”, expresses deep remorse that his “close friends were blacklisted and deprived of their livelihood” because of his decision to name names.

Hayden, Sterling,. Wanderer. [1st ed. New York: Knopf, 1963.]

Actor Gary Cooper, October 23, 1947

(Gary Cooper HUAC Testimony Excerpt, 1947. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gkViHgIs2WM.)

Further Reading

I’d Hate Myself in the Morning: A Memoir

Ring Lardner, Jr., 2000

Lardner, Ring,. I’d Hate Myself in the Morning : A Memoir. New York : [Emeryville, Calif.]: Thunder’s Mouth Press/Nation Books ; Distributed by Publishers Group West, 2000.

The Citizen Writer in Retrospect

Interview with Albert Maltz, 1978-1979

Maltz, Albert. The Citizen Writer in Retrospect. Interview by Joel Gardner. Text, 1978. Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley. https://archive.org/details/citizenwriterinr02malt.

Inquisition in Eden

Alvah Bessie, 1965

Bessie, Alvah Cecil,. Inquisition in Eden. New York: Macmillan, 1965.

MR. STRIPLING: Mr. Reagan, what is your feeling about what steps should be taken to rid the motion-picture industry of any Communist influences?

MR. REAGAN: Well, sir, ninety-nine per cent of us are pretty well aware of what is going on, and I think, within the bounds of our democratic rights and never once stepping over the rights given us by democracy, we have done a pretty good job in our business of keeping those people’s activities curtailed. After all, we must recognize them at present as a political party. On that basis we have exposed their lies when we came across them, we have opposed their propaganda, and I can certainly testify that in the case of the Screen Actors Guild we have been eminently successful in preventing them from, with their usual tactics, trying to run a majority of an organization with a well-organized minority. In opposing those people, the best thing to do is make democracy work. In the Screen Actors Guild, we make it work by insuring everyone a vote and by keeping everyone informed. I believe that, as Thomas Jefferson put it, if all the American people know all of the facts they will never make a mistake.

-Screen Actors Guild President Ronald Reagan before the House Committee on Un-American Activities, October 23, 1947

Novelist Ayn Rand, October 20, 1947

(Ayn Rand at the HUAC Hearings, 1947. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xTeTByQD4go.)

Secondary Analysis

MR. TAVENNER: Were you a member of the Communist Part at the time you were subpoenaed in 1947?

MR. DMYTRYK: No, I was not.

MR. TAVENNER: Had you ever been a member of the Communist Party?

MR. DMYTRYK: Yes, I had been a member from sometime around spring or early summer 1944 until about the fall of 1945. Most of this was during the period when the Communist Party as such was dissolved and the Communist Political Association had taken its place.

MR. TAVENNER: While you were a member of the so-called Hollywood Ten, did you have opportunity to further observe the workings of the Communist Party?

MR. DMYTRYK: I think I can truthfully say that I had much more opportunity to observe the workings of the Communist Party while I was a member of the Hollywood Ten than I did while I was a member of the Communist Party.

MR. TAVENNER: This Committee is endeavoring very strenuously to investigate the extent of Communist Party infiltration into the entertainment field. Are you willing to cooperate with the Committee in giving it the benefit of what knowledge you have, from your own experiences, both while a member of the Communist Party and later?

MR. DMYTRYK: I certainly am.

-Director Edward Dmytryk before the House Committee on Un-American Activities, April 25, 1951

Caught in the Crossfire: Adrian Scott and the Politics of Americanism in 1940’s Hollywood

Jennifer E. Langdon, 2010

Langdon explores the career of Adrian Scott and the role of his and Edward Dmytryk’s 1947 film noir Crossfire, seen at the time as “a frank spotlight on anti-Semitism”, in bringing him before HUAC. Available entirely online, Caught in the Crossfire doubles as a digital archive of sorts; telegrams, FBI memos and more primary documents are accessible via PDF in the book’s endnotes.

Langdon, Jennifer E. Caught in the Crossfire. ACLS ed. New York: Columbia University Press, 2010.

Naming Names

Victor S. Navasky, 1980

This book addresses the more moral questions behind the blacklist, namely those pertaining to what Navasky calls “the Informer Principle”, or whether or not obedience – in this case, naming names – is a matter of virtue.

Navasky, Victor S. Naming Names. New York: Viking Press, 1980.

Cartoonist Walt Disney, October 24, 1947

(Walt Disney HUAC Testimony Excerpt, 1947. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=EWLmfNEzaZo.)

Racializing Subversion: The FBI and the Depiction of Race in Early Cold War Movies

John Noakes, 2003

Noakes argues that the FBI, in searching for Communist infiltration into motion picture, came to equate African-American characters and racial themes with radicalism and subversiveness. The essay gives a unique interpretation that further complicates the popular memory of the blacklist period.

Noakes, John. “Racializing Subversion: The FBI and the Depiction of Race in Early Cold War Movies.” Ethnic and Racial Studies 26, no. 4 (January 1, 2003): 728–49. doi:10.1080/0141987032000087389.

Making the Blacklist White: The Hollywood Red Scare in Popular Memory

Andrew Paul, 2013

Paul’s insightful essay is a memory study of the blacklist period, using three different film portrayals (The Front (1976), Guilty by Suspicion (1991) and The Majestic (2001)) to argue that modern “justice vs. oppression” interpretations of the events gloss over “race, ethnicity, and radical politics” in favor of more ambiguous patriotic themes.

Paul, Andrew. “Making the Blacklist White: The Hollywood Red Scare in Popular Memory.” Journal of Popular Film and Television, no. 4 (2013): 208-18.

- Posters for High Noon, written and produced by “uncooperative witness” Carl Foreman, and On the Waterfront, directed by Elia Kazan, written by Budd Schulberg and co-starring Lee J. Cobb, all “cooperative witnesses”. Both films drew criticisms for their perceived allegorical natures. (Wikimedia Commons)

Communism in Hollywood: The Moral Paradoxes of Testimony, Silence, and Betrayal

Alan Casty, 2009

Casty seeks to muddy a different dichotomy: that between cooperative and uncooperative HUAC witnesses. He criticizes those like the Hollywood Ten who refused to speak, arguing that citing their right to free speech was inconsistent with the Stalinism they weren’t condemning.

Casty, Alan. Communism in Hollywood: The Moral Paradoxes of Testimony, Silence, and Betrayal. Scarecrow Press, 2009.

Screenwriter John Howard Lawson, October 27, 1947

(Howard Lawson HUAC Testimony Excerpt, 1947. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=F7W3XbDZqO4.)

The Final Victim of the Blacklist: John Howard Lawson, Dean of the Hollywood Ten

Gerald Horne, 2006

Horne, Gerald. Final Victim of the Blacklist : John Howard Lawson, Dean of the Hollywood Ten. Berkeley, CA, USA: University of California Press, 2006.

Modern Perspectives

MR. STANDER: I know of some subversion, and I can help the Committee if it is really interested.

MR. VELDE: Mr. Stander-

MR. STANDER: I know of a group of fanatics who are desperately trying to undermine the Constitution of the United States by depriving artists and others of life, liberty, and pursuit of happiness without due process of law. If you are interested in that, I would like to tell you about it. I can tell names, and I can cite instances, and I am one of the first victims of it, and if you are interested in that – and also a group of ex-Bundists, America Firsters, and anti-Semites, people who hate everybody, including Negroes, minority groups, and most likely themselves-

MR. VELDE: Now, Mr. Stander, let me-

MR. STANDER: And these people are engaged in the conspiracy, outside all the legal processes, to undermine our very fundamental American concepts upon which our entire system of jurisprudence exists-

MR. VELDE: Now, Mr. Stander-

MR. STANDER: -and also who-

MR. VELDE: Let me tell you this: You are a witness before this Committee-

MR. STANDER: Well, if you are interested-

MR. VELDE: -a Committee of the Congress of the United States-

MR. STANDER: -I am willing to tell you-

MR. VELDE: -and you are in the same position as any other witness before this Committee-

MR. STANDER: -I am willing to tell you about these activities-

MR. VELDE: -regardless of your standing in the motion-picture industry-

MR STANDER: -which I think are subversive.

-Actor Lionel Stander before the House Committee on Un-American Activities, May 6, 1953

The Hollywood Reporter Blacklist Series, Nov. 30, 2012

“The Most Sinful Period in Hollywood History”, by Gary Baum and Daniel Miller

“An Apology”, by W.R. Wilkerson III

“The Hollywood Brass Who Endorsed the Blacklist”, by Gary Baum and Daniel Miller

“The Blacklist and My Dad”, by Sean Penn

“Blacklist Profiles”, by Scott Feinberg

Through this series of articles run 65 years after the fact, The Hollywood Reporter both acknowledges and apologizes for its role in the period (in 1946, founder and then-publisher Billy Wilkerson published a column, entitled “A Vote for Joe Stalin”, pointing fingers at the likes of Dalton Trumbo, Howard Koch and others that would come to be blacklisted) and then celebrates those affected through portraits and profiles. The series provides a great modern, popular depiction of the period that can serve as a template for others.

HUAC, the Hollywood Ten, and the First Amendment Right of Non-Association

Martin H. Redish and Christopher R. McFadden

Analyzing the period from a legal perspective, Redish and McFadden try to apply the idea of non-association (a counter of the right to free association). The essay posits, though it doesn’t agree, that HUAC was blameless in the studios’ decision to blacklist, and that it was instead their right as private entities to disassociate with those they deemed disagreeable, given their politics.

Redish, Martin H., and Christopher R. McFadden. “HUAC, the Hollywood Ten, and the First Amendment Right of Non-Association.” Minnesota Law Review 85 (2001 2000): 1669.