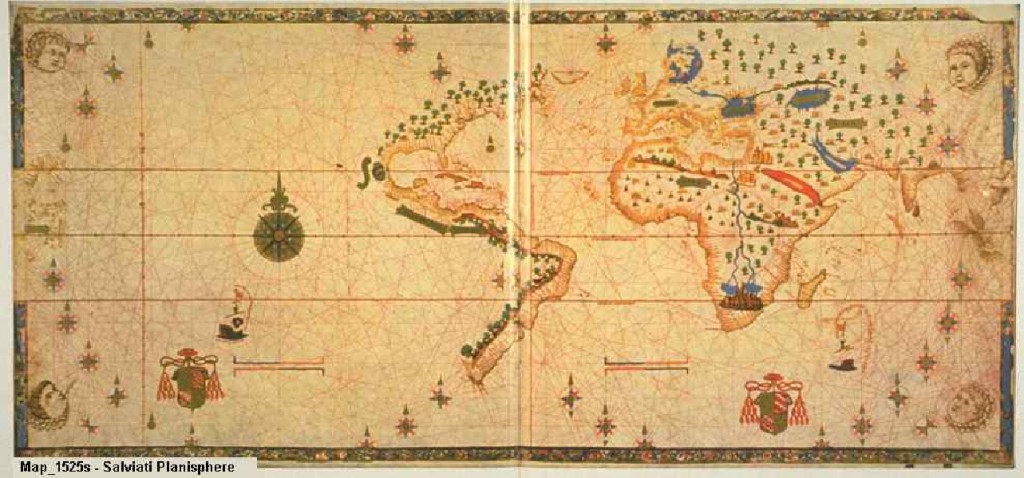

The 1525 Salviati Planisphere shows the Spanish view of the Americas at the time of the Narvaez Expedition.

________________________________________________________

Introduction

In 1528, a Spanish expedition with over 300 men led by the seasoned, one-eyed Panfilo de Narvaez, landed in the area near Tampa Bay. The ambitious expectations of the expeditionary force, to claim vast riches for their king and to save native souls for their Lord, rivaled the Cortez conquest in scope. But eight years later, only four survivors would wander out of the wilderness, naked and wretched, near the Gulf of California. Without an ounce of gold, they could only offer their majesty “news never heard before” of the years they wandered “lost and naked through many and strange lands.”

Shortly after emerging from the wilderness, the four survivors of the Narvaez expedition traveled to Tenochtitlan (Mexico City) where they prepared the so-called Joint Report for presentation to the emperor. The Joint Report is unfortunately lost to history. However, several primary sources related to the Joint Report survive including: a detailed account by Cabeza de Vaca, one of the four survivors; and a transcription of the Joint Report by Oviedo, a contemporaneous historian.

The 16th century world of the survivors’ and the native peoples they encountered is illuminated by examining the expedition’s story. Hundreds of different Native groups inhabited North America, some as different from each other as they were from the invading Caballeros, with widely varied languages, customs and physical appearance. As the expeditionaries struggled across the continent, they interacted with dozens of Native peoples — attacked by some, enslaved for years by others, and finally, worshiped as healers by many. The primary sources provide first hand accounts of the customs and beliefs of these Native groups. The section of this research guide named “Native American Peoples – In Context” provides additional sources for understanding the Native peoples encountered by the expedition.

From the distance of five centuries, the mindset of the caballero can seem impenetrable to the modern reader – they are known for unimaginable brutality and a tough, almost inhuman perseverance. To get at their mindset requires us to ask how they saw themselves. And understanding the caballeros through their own eyes involves, not only examining the survivor’s account of the expedition but also, studying the background of their militaristic ilk, the books they read, the letters they wrote, and the historical context of their time. The “Spanish Caballeros – In Context” section of this research guide provides sources for this examination.

________________________________________________________

Primary Sources

There are three primary sources directly connected to the Narvaez expedition.

- 1542 Relacion (Account): Cabeza de Vaca, one of the survivors and the expedition’s treasurer, wrote an account of the expedition with the intent of securing a royal commission for a territory in the New World. The Joint Report was available to Cabeza de Vaca for reference as he wrote his Relacion which was published in 1542. (Cabeza de Vaca subsequently received a royal commission as Governor of the territories along Rio de la Plata in South America.)

- Oviedo’s Version of the Lost Joint Report: Gonzalo Fernandez de Oviedo y Valdez (often referred to as Oviedo) participated in the colonization of the Caribbean as the official Spanish historiographer. Oviedo provides his own version of the Joint Report in Book 35, chapters 1 – 6 of Historia general y natural de las Indias. In Oviedo’s version, the duplicate testimonies of the survivors contained in the Joint Report are merged into one account and Oviedo also includes his own interpolations but his comments are easily identifiable.

- 1555 Relacion: In 1555, Cabeza de Vaca published another version of the Relacion often referred to as Los Naufragios which can be translated to “shipwrecked ones” or “calamities.” Note that Los Naufragios was created to form part of Cabeza de Vaca’s defense against legal charges brought against him by compatriots on his expedition to Rio de la Plata.

English Translations of Primary Sources

The Narrative of Alvar Nunez Cabeza de Vaca

Translations of the 1542 Relacion as well as Oviedo’s version of the lost Joint Report are provided in this book.

Bandalier, Fanny. The Narrative of Alvar Nunez Cabeza de Vaca. Barre, MA: The Imprint Society, 1972.

Castaways, The Narrative of Alvar Nunez Cabeza de Vaca

Contains a translation of the 1555 Relacion.

Pupo-Walker, Enrique. Castaways, The Narrative of Alvar Nunez Cabeza de Vaca. Translated by Frances M. Lopez-Morillas. University of California Press, 1993.

________________________________________________________

Expedition History And Analysis

Alvar Nunez Cabeza de Vaca; His Account, His Life, and the Expedition of Panfilo de Narvaez

This critically acclaimed three volume set contains: a translation of the 1542 Relacion; a detailed analysis of the Narvaez expedition comparing Cabeza de Vaca’s account to Oviedo’s; and deep biographical information on Cabeza de Vaca. One reviewer calls this book a “historiographical tour de force” (Patricia Kay Galloway) and another calls it “a magnificent work” (Neil L. Whitehead.) This is the go-to place for all things Cabeza de Vaca.

Adorno, Rolena, and Patrick Charles Pautz. Alvar Nunez Cabeza de Vaca; His Account, His Life, and the Expedition of Panfilo de Narvaez. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1999.

We Came Naked and Barefoot

This book consists of translations of the Relacion and the Oviedo account as well as the author’s dissertation in which he traces the route of Cabeza de Vaca and his companions from the coast of Texas to Spanish settlements in western Mexico. The dissertation is rich in information about the native groups, vegetation, geography, and material culture that the companions encountered.

Krieger, A. D. We Came Naked and Barefoot: The Journey of Cabeza de Vaca Across North America. Austin: University of Texas Press, 2002.

Brutal Journey

The Narvaez expedition is described in narrative style in this book. The author draws on the accounts of the first explorers and the most recent findings of archaeologists and academic historians to tell the story.

Schneider, Paul. Brutal Journey. New York: Henry Hold and Company, 2006.

Conquistador in Chains

This book portrays the Narvaez expedition as a a life-changing adventure for Cabeza de Vaca that leads him to seek a different kind of conquest — one that would be just and humane, true to the Spanish religion and law. Note that while their enslavement was certainly a miserable experience, the survivors were never in chains as the book title suggests – the expeditionaries submitted themselves to various tribes in order to survive.

Howard, David A. Conquistador in chains : Cabeza de Vaca and the Indians of the Americas. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 1997.

The Negotiation of Fear in Cabeza de Vaca’s Naufragios

In this article, Adorno focuses on the process of adaptation and survival in Cabeza de Vaca’s interaction with native Americans.

Adorno, Rolena. “The Negotiation of Fear in Cabeza de Vaca’s Naufragios.” Representations, No. 33, Special Issue: The New World, 1991: 163-199.

Cabeza de Vaca and the Problem of First Encounters

This short article describes the enslavement of the four survivors contrasting Western systems of slavery with Native American customs. The survivors were tolerated by the natives, like stray dogs, as long as they were useful.

Resendez, Andres. “Cabeza de Vaca and the Problem of First Encounters.” Historically Speaking Vol. 10(1), 2009 : 36-38.

In Search of Cabeza de Vaca’s Route across Texas

Adorno & Pautz say that this article is “one of the most important articles on the Narvaez expedition’s route written in recent years.”

Chipman, Donald E. “In Search of Cabeza de Vaca’s Route across Texas: An Historiographical Survey.” The Southwestern Historical Quarterly , Vol. 91, No. 2, 1987: 127-148.

Observations on the Use of Manual Signs and Gestures in the Communicative Interactions between Native Americans and Spanish Explorers of North America

This article focuses on the communication via manual signs described by our hero, Cabeza de Vaca, and by Bernal Díaz del Castillo. Their reports reveal that both the European explorers and the indigenous peoples relied on manual signs and gestures to help overcome spoken-language communication barriers. They also show that manual signing was already being widely used by the native peoples of North America at the time of their first contacts with European explorers.

Bonvillian, John D., Vicky L. Ingram, and Brendan M. McCleary. “Observations on the Use of Manual Signs and Gestures in the Communicative Interactions between Native Americans and Spanish Explorers of North America: The Accounts of Bernal Díaz del Castillo and Álvar Núñez Cabeza de Vaca.” Sign Language Studies 9, no. 2, 2009: 132-165.

________________________________________________________

Spanish Caballeros – In Context

Amadis of Gaul

With origins in the middle ages, the story of Amadis of Gaul developed into a legend combining a little history and mostly fantasy. The rambling tale depicts the medieval knight Amadís as courteous, gentle, sensitive and as a Christian who battles monsters and defends the honor of his childhood love Oriana. Printed in 1508, Amadis of Gaul enjoyed wild success on the Iberian peninsula. The Narvaez expeditionaries were undoubtedly familiar with this rambling tale and their values influenced by the ideals of knighthood presented in the story.

Montalvo, Garciordonez De. Amadis of Gaul. Translated by Robert Southey. 3 vols. London: John Russell Smith, 1872.

Books of the Brave

Books of the Brave, originally published in 1949, is an account of the introduction of literary culture to Spain’s New World. Leonard’s study documents the works of fiction that accompanied and followed the conquistadores to the Americas and goes on to argue that popular texts influenced these men and shaped the way they thought and wrote about their New World experiences. Rolena Adorno’s introduction brings the reader up to date on developments in cultural-historical studies that have shed light on the role of books in Spanish American colonial culture.

Leonard, Irving A. Books of the Brave. Oxford, England: University of California Press, Ltd., 1992.

The Journey of Fray Marcos de Niza

One of the four Narvaez expedition survivors was Estebanico, a black African slave born in Morocco. During their eight years of hardship, Estebanico learned many of the native languages and served as translator for the band of survivors. Following the Narvaez expedition, Estebanico was recruited by Fray Marcos de Niza on a mission to find the mythical seven cities of Cibola thought to be in the American southwest. The Journey of Fray Marcos de Niza describes this mission, another tragic adventure.

Hallenbeck, Cleve. The Journey of Fray Marcos de Niza. Dallas: Southern Methodist University Press, 1987.

Estevanico, Negro Discoverer of the Southwest

The two main topics analyzed in this article are the questions of Estevanico’s race and of his death during the journey with Fray Marcos.

Logan, Rayford W. “Estevanico, Negro Discoverer of the Southwest: A Critical Reexamination.” Phylon Vol. 1, No. 4, 1940: 305-314.

Estevanico’s Legacy

In this article, the author uses Estevanico’s story to tackle the question, “How can we propose comparative studies on transatlantic cultural relations that do not replicate Eurocentric models of understanding the colonial subjects?” Estevanico’s role has sometimes been overplayed by historian’s in the laudable attempt to include the excluded actors of history into textbook narratives. Adorno examines these attempts and tries to offer a more balance perspective.

Adorno, Rolena. “Estevanico’s Legacy: Insights into Colonial Latin American Studies.” Museum Tusculanum

The Worlds of Christopher Columbus

This book about the life and times of Christopher Columbus provides an understanding of the motives and methods of the Spanish explorers. Phillips provides the background behind the unleashing of Spanish exploration and conquest that started in 1492 and this background is equally relevant to the Narvaez expedition.

Phillips, William D., and Carla Rahn Phillips. The Worlds of Christopher Columbus. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1993.

Knights of Spain, Warriors of the Sun

The expedition of Hernando de Soto departed soon after the Narvaez survivors returned to civilization and covered some of the same southern territory. With Knights of Spain, Warriors of the Sun, anthropologist Charles Hudson provides an in depth analysis of the de Soto expedition. He uses the diaries of the de Soto expeditionaries to arrive at a route that was likely traversed by the caballeros.

Hudson, Charles. Knights of Spain, Warriors of the Sun: Hernando de Soto and the South’s Ancient Chiefdoms. Athens, Georgia: University of Georgia Press, 1997.

________________________________________________________

Native American Peoples – In Context

One vast winter count

This work traces the histories of the Native peoples of the American West from their arrival thousands of years ago to the early years of the nineteenth century. Emphasizing conflict and change, One Vast Winter Count offers a new look at the early history of the region by blending ethnohistory, colonial history, and frontier history. Drawing on a wide range of oral and archival sources from across the West, Colin G. Calloway offers an unparalleled glimpse at the lives of generations of Native peoples in a western land soon to be overrun.

Calloway, Colin Gordon. One vast winter count: the Native American West before Lewis and Clark. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2003.

Handbook of North American Indians

The Handbook of North American Indians is a fifteen volume enclopedia (with five more volumes planned) that documents information about all Native peoples of the Americas north of Mesoamerica, including cultural and physical aspects of the people, language family, history, and prehistory. Leading authorities have contributed chapters to each volume. Volumes cover geographical areas of North America and include separate chapters on all tribes of that area. The set is a reference work for historians, anthropologists, other scholars, and the general reader. The volumes cited here describe the Native peoples in the areas through which the Narvaez expeditionaries traveled.

Ortiz, Alfonso. Handbook of North American Indians. Vol. 9 Southwest. 17 vols. Washington: Smithsonian Institution, 1979.

Ortiz, Alfonso. Handbook of North American Indians. Vol. 10 Southwest. 17 vols. Washington: Smithsonian Institution, 1983.

Fogelson, Raymond D. Handbook of North American Indians. Vol. 14 Southeast. 17 vols. Washington: Smithsonian Institution, 2004.

The Indian Tribes of North America

This one-volume guide to the Indian tribes of North America covers all groupings such as nations, confederations, tribes, sub-tribes, clans, and bands. Formatted as a dictionary, or gazetteer, and organized by state, it includes all known tribal groupings within the state and the many villages where they were located. The text includes such facts as the origin of the tribal name and a brief list of the more important synonyms; the linguistic connections of the tribe; its location; a brief sketch of its history; its population at different periods; and the extent to which its name has been perpetuated geographically.

Swanton, John Reed. The Indian Tribes of North America. Washington: Genealogical Publishing Company, 1952.

Conquest: The Destruction of the American Indios

The author argues that a series of economic and social factors played a role in the disastrous decline of the native populations in addition to the destruction caused by ‘imported’ diseases. He argues that the catastrophe was not the inevitable outcome of contact with Europeans but was a function of both the methods of the conquest and the characteristics of the subjugated societies. Sources include surviving documentation from conquistadors, religious figures, administrators, officials, merchants and the direct testimony of Native Americans of their harsh subjugation at the hands of the Europeans

Bacci, Massimo Livi. Conquest: The Destruction of the American Indios. Cambridge: Polity Press, 2008.

________________________________________________________

Archives and Collections with Related Material

General Archive of the Indies (Archivo General de Indias)

The House of Trade was the sixteenth century epicenter for launching Spanish expeditions and the documents from the House of Trade are now maintained in the General Archive of the Indies located in Seville. These documents originated from several organizations operating in the House of Trade: the Council of the Indias; and the Casa de la Contratación (Contracting Company.) The types of documents include trade contracts, officer appointments and maps of trade routes.

Royal Academy of History (Real Academia de la Historia)

The Royal Academy of History has a library for study and research of the history of Spain and Spanish America. The library contains a large collection of printed books and pamphlets printed as well as manuscripts and handwritten documents ranging from the Middle Ages to the present. The collections contain the research of scholars themselves and other historians of the eighteenth, nineteenth and first half of the twentieth centuries.

Library of Congress: Exploring the Early Americas

This online exhibition provides insight into indigenous cultures, the drama of the encounters between Native American and European explorers and settlers, and the pivotal changes caused by the meeting of the American and European worlds. The exhibition features selections from the more than 3,000 rare maps, documents, paintings, prints, and artifacts that make up the Jay I. Kislak Collection at the Library of Congress. The exhibition has three major themes: Pre-Contact America; Explorations and Encounters; and Aftermath of the Encounter.

American Journeys contains more than 18,000 pages of eyewitness accounts of North American exploration, from the sagas of Vikings in Canada in AD1000 to the account of Cabeza de Vaca and the diaries from the de Soto expedition.

________________________________________________________