by Nicole Close

Introduction

In medieval Europe, there was no fine distinction between magic and religion. The Church’s magical and devotional facets were often inextricably linked to one another. This changed with the introduction of the Protestant Reformation in the sixteenth century. The Reformation started in Germany, but quickly spread and splintered Catholic Europe. Protestantism addressed key problems with the Church: the use of magic for secular reasons and its claim to have access to God’s supernatural power. This movement caused a decline in not only the use of magic, but the belief in magic as well. However, this weakening of the ties between magic and religion may have only occurred in Catholicism.

The Reformation can be considered a time of increased rationalism, and thus accounts for the decrease in the belief of magic. However, this denial of magic does not appear to apply to Jews, as seen through the persistence of ritual murder accusations. Why does this inconsistency regarding magic exist? How did the Jews become associated with magic, particularly satanic magic? This guide’s purpose is to compile documents that may address this disparity between the rational decline in the belief of magic and the irrational continuance in the belief of Jewish magic, particularly pertaining to ritual murder.

Topic Overview

Religion and the Decline of Magic (Book)

A key work in regards to this research guide, Keith Thomas’ book provides a substantial history of the Reformation and how it affected religion. Its scope is mostly sixteenth and seventeenth-century England. There is detailed information on the magical beliefs and practices in medieval Christianity. Then, Thomas thoroughly explores the Reformation and details its impact of causing a decline in magic. However, there is little mention of the effect on Jews in particular. One instance of mention was about how the fear of witches was not usually interchangeable with the fear of Catholics or Jews. Thomas describes that witchcraft cases are unique in that the accused are in close proximity to the accuser, practically neighbors, and that it was used to explain a local tragedy. Despite Thomas saying this is a function of only witchcraft accusations, I find this to be very similar to ritual murder accusations. In which case, the displacement of witches with Jews would become easier to achieve, for their role would practically be the same.

Thomas, Keith. Religion and the decline of magic: Studies in popular beliefs in sixteenth and seventeenth century England. New York: Oxford University Press, 1997.

Jewish Magic and Superstition (Book)

An important book for this guide, as it is entirely about Jewish magic. Trachtenberg writes about all the political, social, economic, and religious factors that account for the belief in Jewish magic, especially the ritual murder accusation. He proclaims that this myth has been the most persistent and popular form and has had the most serious consequences for the Jewish community. He explains Christians as having misunderstood Jewish religious rituals, and causing Jews to either stop practicing them or be persecuted. Also addressed is the double standard surrounding magic in this time: Christians would use Jewish magic for their own benefit, but also punish magic that they considered satanic.

Trachtenberg, Joshua. Jewish Magic and Superstition: A Study in Folk Religion. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2004.

The Reformation, Popular Magic, and the “Disenchantment of the World” (Journal Article)

This article by Scribner focuses on the complicated relationship between magic and religion, both before and after the Reformation. He defines both terms in order to separate them. Magic is the attempt of seizing divine power in order to use it, while religion is human faith and devotion toward divine power. Scribner follows magic and religion throughout history in order to see how and why the two became so interconnected, and how the Reformation affected this relationship.

Scribner, Robert. “The Reformation, Popular Magic, and the ‘Disenchantment of the World’.” The Journal of Interdisciplinary History 23 (1993): 475-94.

Primary Sources

The Twelve Conclusions of the Lollards

Lollardy was a political and religious movement initially led by John Wycliffe. The Twelve Conclusions of the Lollards was written by the Lollards, Wycliffe’s followers, in 1395. This document was presented to the Parliament of England and criticized the then-current state of the Church. Of particular importance is the Fourth Conclusion, which deals with transubstantiation. Transubstantiation is the idea that the sacrament of the Eucharist was a real transformation in which priests turn bread and wine into the body and blood of Christ. The Lollards did not believe that priests had such magical powers, and thought transubstantiation led to idolatry. This leads to the Fifth Conclusion in which they write that consecration is related to necromancy, not theology. The Lollards parallel with many Reformation themes, and one that is key to my research is the disbelief in the Church’s ability to control God’s power.

“The Twelve Conclusions of the Lollards (Middle English, Literally Translated into Mod. English).” The Geoffery Chaucer Page. The Twelve Conclusions of the Lollards

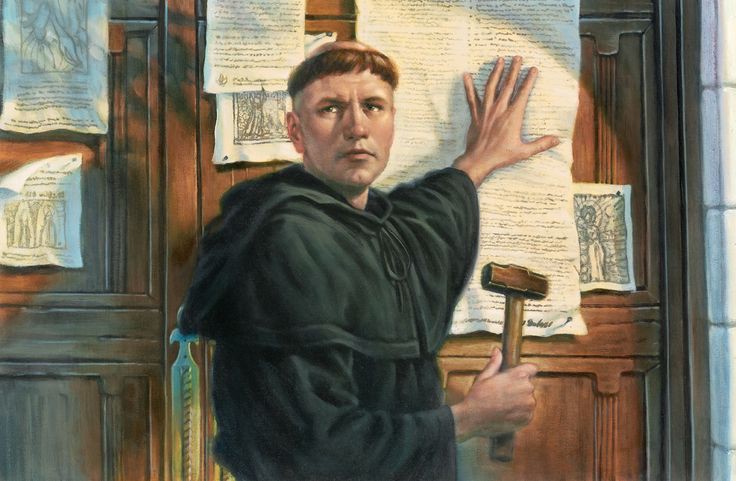

The Ninety-Five Theses on the Power and Efficacy of Indulgences

Written by Martin Luther in 1517, this work is often considered the beginning of the Protestant Reformation. It mainly deals with the church’s practice of selling indulgences. Luther believed that God wanted his followers to genuinely repent for their sins. He also believed, and this is the thrust of Protestantism, that faith alone, not deeds, would lead to salvation.

Luther, Martin. Luther’s Ninety-five Theses. Philadelphia: Fortress Press, 1957.

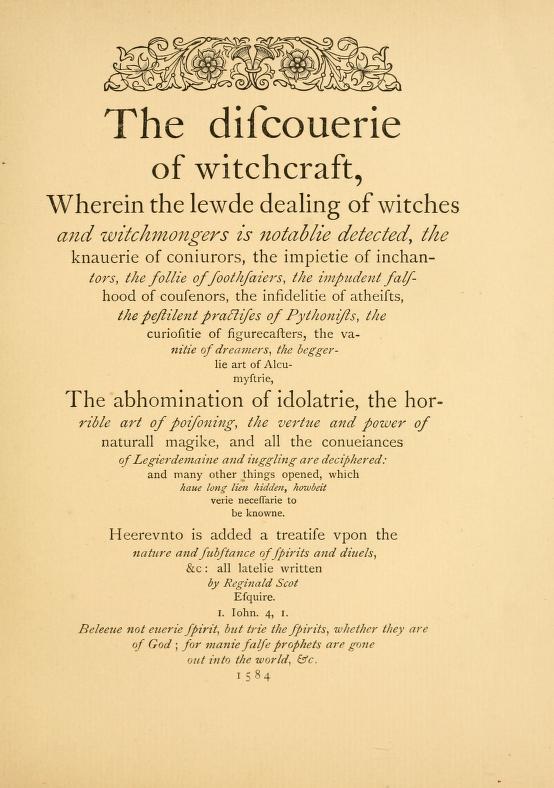

The Discoverie of Witchcraft

Published in 1584, this work by Reginald Scot is considered the first on the topic of magic. Scot believed the accusation of witchcraft was irrational and blamed the Roman Catholic Church. Scot shows the magical elements in medieval Catholicism and denies them. He writes about the power of exorcism, and how it has not been operational since the time of the Apostles, as it was a special gift of theirs. His goal was to protect those most susceptible to accusations, like the poor and the old, and to spread this disbelief of witchcraft to the public.

Scot, Reginald. The Discoverie of Witchcraft. New York: Dover Publications, 1972.

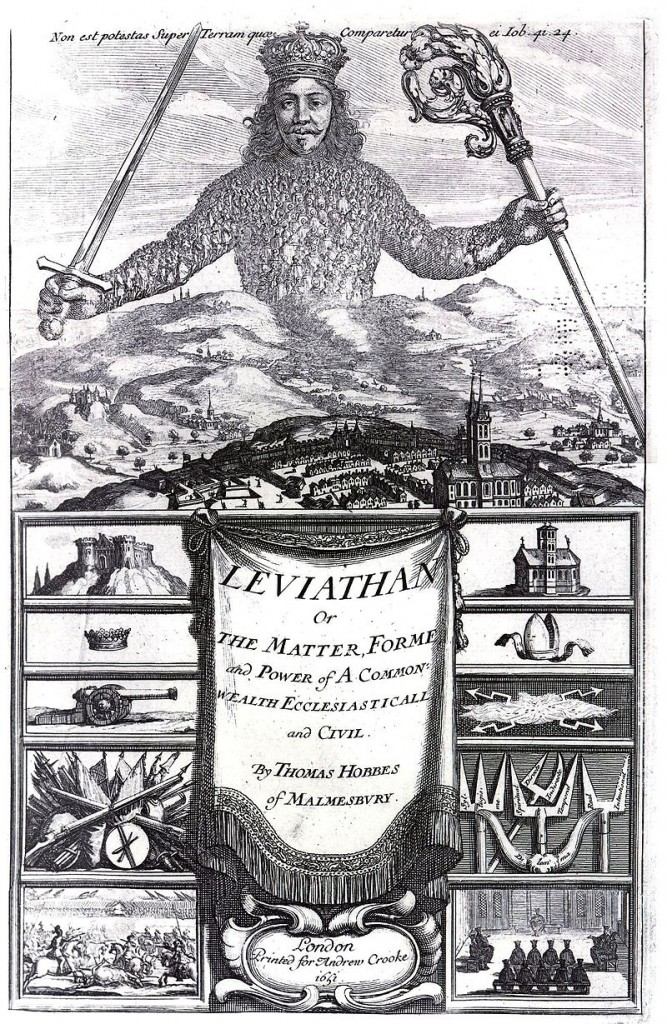

Leviathan

Thomas Hobbes’ Leviathan was written in 1651. Of particular importance to this guide is Part IV: Of the Kingdom of Darkness. By darkness he is not referring to Hell or Purgatory, but instead the darkness of ignorance. He finds that one main cause of ignorance in society is churches and that churches are also the ones who benefit from this ignorance. For example, he writes about consecration being turned into conjuration; he does not believe that by uttering an appropriate incantation that you change bread and wine. Hobbes believed that scriptures had been misinterpreted by the Church, and thus caused this public ignorance.

Hobbes, Thomas, and J. C. A. Gaskin. Leviathan. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1998.

Secondary Sources

A Tale of Ritual Murder in the Age of Louis XIV (Book)

This book by Pierre Birnbaum focuses on the ritual murder trial of Raphaël Lévy. Chapter 1 describes the context of the scene, which was seventeenth-century France, a supposedly rational time and place. Birnbaum writes about accusations of witchcraft and how after several misfortunes, these accusations seemed to cease. But with this decline, there was the opportunity to return to an old target of accusations, the Jews. The Church increasingly wouldn’t allow witches to become scapegoats, so they turned to another group that was different from them. There had been a long period without ritual murder accusations, so Birnbaum argues that this decline in the belief of witchcraft spurred this blood libel case. Birnbaum addresses the hypocrisy of the claims of Jewish magic, for all of medieval Europe had believed in and been involved with magic. Also of import is the transfer of Devil-inspired magic from witches to the Jews.

Birnbaum, Pierre. A Tale of Ritual Murder in the Age of Louis XIV: The Trial of Raphaël Lévy, 1669. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2012.

Warrant for Genocide (Book)

This book by Cohn mostly deals with more modern anti-Semitism, particularly the time leading up to World War II. However, there is a brief history on the traditional view that Jews were mystic beings who had their powers bestowed upon them by Satan. He also introduces ritual murder accusations, which started in the twelfth century. Cohn writes about demonological views of Jews; Jews were treated as enemies of the Catholic religion, as they were seen as agents of the Devil himself. Furthermore, this perspective held by Christian clerics then disseminated into popular belief, so Jews were not separated from the public by just religion, but by the fact that they were regarded as subhuman, demonic creatures.

Cohn, Norman. Warrant for Genocide: The myth of the Jewish world conspiracy and the ‘Protocols of the Elders of Zion.’ London: Serif, 2005.

The Myth of Ritual Murder (Book)

This book focuses on Jewish magic in Reformation Germany, particularly on how it was perceived by Christians. There are in-depth explanations of various uses of magic by all religions in the Middle Ages, not just Judaism. Hsia discusses the role of the Reformation in ritual murder cases, particularly regarding learned and popular views. Hsia also examines the recurring themes of child sacrifice and blood in these cases.

Hsia, R. Po-chia. The Myth of Ritual Murder: Jews and Magic in Reformation Germany. London: Yale University Press, 1988.

Popular Culture and Popular Movements in Reformation Germany (Book)

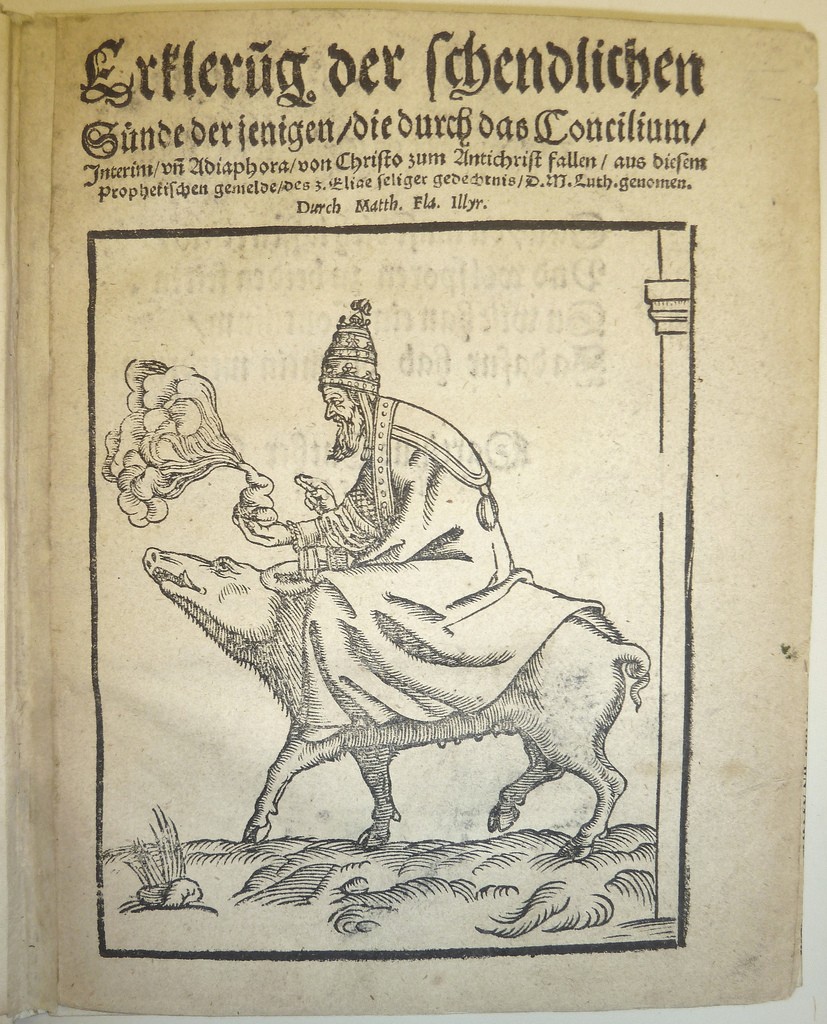

Scribner writes about the German Reformation and how it was the first great age of mass propaganda due to the printing press. He provides many images in his book to show this. Martin Luther attacked the papacy as being the Antichrist, and he produced propaganda to spread this belief. The image above illustrates Luther’s views. It is the pope riding a sow with steaming excrement in one hand, while he gives a blessing with the other. Luther thought of Germany as the sow, being led by the lies of the Roman Catholic Church. However, there is more to this image. There is an allusion to the anti-Semitic “Jewish sow”, in which Jews are portrayed in obscene contact with sows, usually by eating their excrement.

Scribner, Robert. Popular Culture and Popular Movements in Reformation Germany. London: The Hambledon Press, 1987.

Luther’s House of Learning (Book)

This book is about Reformers as educators, and the conflict between their secular and religious goals in education. Strauss briefly mentions magic, and the frustrations of Protestant clerics who had to sift through superstitions in their religious practices. The public believed in the effectiveness of magic, as did the leaders, but the latter knew it was irrational and the work of the Devil. With magic being such an ingrained part of religious rituals, the clerics had a hard time convincing the public of changing their customs.

Strauss, Gerald. Luther’s House of Learning: Indoctrination of the Young in the German Reformation. London: The John Hopkins University Press, 1978.

From Sorcery to Witchcraft (Journal Article)

In this article, Bailey writes about how early conceptions of magic were transformed into witchcraft in the later Middle Ages. For example, the idea of magic as coming from the Devil is transformed and illustrated through the supposed pact made between witches and the Devil. If we take into account the view in which Jews have demonic magic, then perhaps when witchcraft accusations are no longer tolerated in Europe, Jews are able to fulfill this role and thus the return and continuation of the ritual murder accusation. Bailey also addresses a possible connection between the Protestant Reformation and witchcraft accusations in which the reformation of the Church caused increased tensions concerning demonic corruption.

Bailey, Michael D. “From Sorcery to Witchcraft: Clerical Conceptions of Magic in the Later Middle Ages.” Speculum 76, no. 4 (2001): 960-90.

On Witches, Jews and Heretics (Thesis)

This thesis is about thirteenth and fourteenth-century Europe, with a particular focus on England. She writes about three major groups who were not members of the Roman Catholic Church, and therefore threatening to it: Jews, heretics, and witches. Some of the same accusations were made against all three groups, particularly charges of cannibalism and ritual murder. However, Dallmann-Jones also notes some differences, like how well poisoning was reserved for Jews and lepers, and how Jews were never fully accused of witchcraft. She gives a possible explanation of witchcraft being an inversion of Christianity, so it had to be applied to a Christian; nevertheless, Jews were believed to have harmful magic. Another connection between these three groups was their so-called connection to the Devil. There was also dehumanization of these outsiders in order to make their torture and execution easier.

Dallmann-Jones, Amy. “On Witches, Jews and Heretics: The Catholic Church and Its Enemies in Thirteenth and Fourteenth Century England.” PhD diss., California State University, 1996.

Rerooting the Faith (Journal Article)

This article is about the Protestant Reformation as a means to re-Christianize Europe. The reformers felt that the Catholic Church, in its then-current state, was idolatrous. They wanted a more “pure” form of Christianity, in which people had more genuine faith in God. This work also addresses Protestant opinions on Jews, in which not converting to Christianity led to hostile feelings. Therefore, the Protestant Reformation mission to re-Christianize Europe helped to create a climate of greater intolerance towards Jews.

Hendrix, Scott. “Rerooting the Faith: The Reformation as Re-Christianization.” Church History 69, no. 3 (2000): 558-77.