Introduction

When studying the inner workings of Soviet society and government, one cannot but notice the intricate weaving between ideology and reality. This phenomenon is not only observed during the course of the Soviet Union’s existence, but it became part of how the system worked. In the Soviet Union, science and technology served as an important part of national politics, practices, and identity. Soviet science was constructed by scientists who worked in Imperial Russia and where part of the intelligentsia, and who were allowed to continued their work in the USSR. While it was envisioned as pure science and innovation, Soviet science tended to fall short when it came to pragmatic terms. Nevertheless, biology, chemistry, materials science, mathematics, and physics were all fields in which the Soviet Union obtained individuals of high qualifications and critical acclaim. Although the sciences were less rigorously censored than other fields, suppression of ideas was still very present. The banning of modern theorems and use scientific ideas in the name of Marxism caused a gap in the exchange of ideas with outside world, bringing about isolation of the Soviet scientific community.

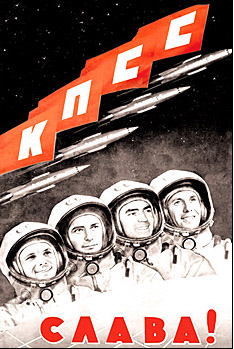

Soviet technology was most highly developed in the fields of nuclear physics, where policy makers set aside sufficient resources for research in order to compete with the West in an arms race. Thus, the Soviet Union was the second nation to develop an atomic bomb, in 1949, four years after the United States. In addition, the Soviet Union detonated a hydrogen bomb in 1953, a mere ten months after the United States. The space program was also part of Soviet pride. In October 1957 the Soviet Union launched the first artificial satellite, Sputnik 1, into orbit; and in April 1961, Yuri Gagarin became the first man in space. This research guide focuses on science and technology, and their development throughout the duration of the USSR. But more than that, it plans to show how politics and ideologies can mar the development of scientific research and empirical thinking.

On Science in the USSR and Its Scientific Culture

Science in Russia and the Soviet Union

- This book is an excellent as an introductory chapter into the scientific culture of Russia. It begins with the development of science before the 1800, under Imperial Russia, and it furthers the story on into the October Revolution and science under the Soviet Union. In addition, it provides an idea of how science and scientific discovery is affected by change in both politics and ideology of both the government and the governed. The book also includes two appendix chapters that delve into the strengths and weaknesses of Soviet science.

- Graham, Loren R.. Science in Russia and the Soviet Union: A Short History. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1993.

Soviet Science

- Soviet Science is a 1590s compilation of different topics in Russian and Soviet science presented in a symposium held in Philadelphia. It attempts to place emphasis on factual reporting of Soviet science, but recognizes that “Communist science” is more concerned with the effect on science of politics than with science itself. The disciplines the books goes over are genetics, physiology and pathology, psychology an psychiatry, the scientific method, social science, soil science, physics, chemistry, and mathematics. It also brings forth the question on intellectual freedom in the USSR.

- Christman, Ruth C., ed. Soviet Science. Baltimore: National Science Foundation, 1952.

The State of Soviet Science

- This book is a compilation of essay that discuss the different aspects of science disciplines in the USSR. While the majority of the topics is on natural sciences, Soviet philosophy and psychology studies are also discussed.

- The State of Soviet Science,. Cambridge, Mass.: M.I.T. Press, 1965.

Soviet Science and Technology

- Compiled from papers and discussions at a 1976 National Science Foundation Workshop, this book takes as main subjects the Soviet science policy and organization, the relationships with the economic and political systems, the dependence on Western technology, and prospects for cooperation between the USA and the USSR.

- Thomas, John R. (ed.), and Ursula M. Kruse-Vaucienne (ed.). Soviet Science and Technology: Domestic and Foreign Perspectives.. Washington: George Washington University for NSF, 1977.

Science and Philosophy in the Soviet Union

- In his book, Graham investigates the relation of science to what he calls “dialectical materialism” in the Soviet Union. In asuccessful attempt to cover nearly all modern science in order to explain the Soviet role, Graham starts with the origins of the Russian philosophy of dialectical materialism in the writings of Engels and Lenin. Graham goes on to explain the interweaving of scientific and philosophical issues in physics, chemistry, the origin of life, cybernetics, and psychology. Lysenkoism is discussed as well, and Graham brings the question of method and why in many fields Soviet scientists prove more sensitive to methodological and philosophical aspects than their Western colleagues.

- Graham, Loren R.. Science and Philosophy in the Soviet Union. 1st ed. New York: Knopf, 1972.

Science, Philosophy, and Human Behavior in the Soviet Union

- Again, Graham presents his mature assessments and conclusions in this revised edition of Science and Philosophy in the Soviet Union (1972), which adds new chapters on human behavior and, as before, covers specific branches of science: genetics, psychology, chemistry, quantum mechanics, relativity physics and others.

- Graham, Loren R.. Science, Philosophy, and Human Behavior in the Soviet Union. New York: Columbia University Press, 1987.

Stalin and the Soviet Science Wars

- While the Soviet Union confronted postwar reconstruction and Cold War crises, Joseph Stalin began to study scientific disputes and dictate academic solutions. He sparked a discussion of what he called “scientific” Marxist-Leninist philosophy, edited reports on genetics and physiology, adjudicated controversies about modern physics, and wrote essays on linguistics and political economy. In his book, Pollock uses previously unexplored archival documents to demonstrate that Stalin was in fact determined to show how scientific truth and Party doctrine reinforced one another. Based on the premise that Socialism was supposed to be scientific, and science ideologically correct, Stalin embodied the perfect melange between power and knowledge, which can be understood only within the context of international tensions, institutional conflicts, and the growing tensions between science and Party-dictated truths.

- Pollock, Ethan. Stalin and the Soviet Science Wars. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 2006.

“‘Mathematical Machines’ of the Cold War”

- This paper examines how early Soviet computing was shaped by the interplay of military and ideological forces, and affected by the attempts to ‘de-ideologize’ computers from Marxism, a point where many scientist opted for separation of science and ideology. In addition, the paper compares the impact of the Cold War on science and technology, both in the Soviet Union and the United States.

- Gerovitch, Slava. “‘Mathematical Machines’ of the Cold War: Soviet Computing, American Cybernetics and Ideological Disputes in the Early 1950s.” Social Studies of Science 31, no. 2 (2001): 253-287.

“Celebrating Tomorrow Today”

- This paper introduces the history of a unique museum of nuclear energy, the Pavilion for Atomic Energy, at the ‘Exhibition of the Achievements of the People’sEconomy in Moscow, from its inception in 1956 to its closing in 1989. The paper proposes that the pavilion’s exhibitions on nuclear energy, staged as pivotal to technical progress, not only reinforced a vision of the country’s scientific and technological potential, but also contributed significantly to the Soviet political vision. Based on archival documentsand published material, the paper traces shifts in the pavilion’s tasks, and attempts toconvey how these shifts mirror changing concepts of the intended visitors. It addresses differences and similarities between Soviet and Western approaches to public displays of science and technology.

- Schmid, Sonja D. “Celebrating Tomorrow Today: The Peaceful Atom on Display in the Soviet Union,” Social Studies of Science 36, no. 3 (2006): 331-365.

- This is the official film released on the famous “severed dog head” experiment performed by Sergei S. Brukhonenko, a medical scientist during the Stalinist era. He was also critically acclaimed for his research as a large contribution to the development of open-heart surgery in Russia.

- “Experiments in the Revival of Organisms”, YouTube video, 10:00, posted by “happysmellyfish,” February 4, 2009, http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=KDqh-r8TQgs.

- This video presents an interview of Leonid Glebov, research professor at the University of Central Florida, CREOL School of Optics. Here, he describes Russian optic science (the field in which he worked in) as isolated from the rest of the world. In addition, he goes on to describe the benefits of being a scientist before the fall of the Soviet Union, and the hardships of loosing all his funding and privileges after the fall of the government. Glebov emphasizes the idea that science should be pure and away from politics, for a scientist should not be a politician.

- “Leonid Glebov: Hard Lessons Learned in Soviet Science,” YouTube video, 6:36, posted by “SPIETV,” June 27, 2011, http://www.youtube.com/watch?feature=player_embedded&v=MTBiXZFuPpo

Space, the Final Fronteir: The Soviet Space Program

- An hour-long video, this documentary narrates the story of the rise and fall of the Soviet Space Program. Among many aspects, it touches on American-Soviet relations, NASA’s involvement, and the successes (and failures) of the Soviets in space.

- “RISE and FALL of the Russian Space Program,” YouTube video, 51:05, posted by “NASA FLix,” September 16, 2012, http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=242XVAmccZ0.

- This is a briefing by the CIA in 1981. The presentation describes what they call the “Jekyll-and-Hyde” nature of the Soviet space program. In addition, it grants the viewer a contemporary perspective on Soviet scientific (and power) advancement, as seen from the USA point-of-view.

- “CIA Video Briefing: Soviet Space Program 1981,” YouTube video, 7:40, posted by “TheConquestofSpace,” November 14, 2011, http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kVGqpsmOClc.

Accomplishments

List of Noble Prize winners:

Physics

- 1958: Pavel Cherenkov, Ilya Frank and Igor Tamm — the Cherenkov effect

- 1962: Lev Landau — theories about condensed matter, superfluidity

- 1964: Nikolay Basov and Aleksandr Prokhorov — quantum electronics

- 1978: Pyotr Kapitsa — inventions and discoveries in cryophysics

Chemistry

- 1956: Nikolai Semenov — application of the chain theory to varied reactions (1934–1954) and to combustion processes; theory of degenerate branching

Science, Policy, and Politics

Science and Technology as an Instrument of Soviet Policy

- This book is based largely on pronouncements of Soviet political leaders, which are examined and quoted in order to demonstrate a number of features of the Soviet research and development establishment. From this, it is taken that, despite the cut-backs in the American defense system at the time, Soviet leaders continued to assign science and technology a central place in their strategy to obtain the upper hand. This strategy combines the elements of advanced economic development, international prestige, and, most importantly, military power.

- Harvey, Mose L., Leon Gouré, and Vladimir Prokofieff. Science and Technology as an Instrument of Soviet Policy. Coral Gables, Fla.: Center for Advanced International Studies, University of Miami, 1972.

Science Policy in the USSR

- This lengthy study discusses policies on science in the Soviet Union at the time of its publication. While not a historical narrative, this book provides a bulk of information for those interested on contemporary Soviet policy and hierarchy in relation to science and scientific research.

- Zaleski, Eugène, JP Kozlowski, H Wienert, RW Davies, MJ Berry, and R Amann.Science Policy in the USSR. Paris: Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development, 1969.

Science, Technology and Ecopolitics in the USSR

- Although enormous industrial advances were made in the USSR, the country still lagged behind the West in the post-industrial age. What the Soviets could not build or manufacture, they had to get from the West. The author traces the development of the Soviet malaise, while suggesting that a future authoritarian regime has the possibility to revive the technological race. In addition, he also replies to the academic debate on the excesses of modern technology in the West, with harsh criticism of feminist and post-modernist perspectives.

- Rezun, Miron. Science, Technology, and Ecopolitics in the USSR. Westport, Conn.: Praeger, 1996.

Lysenko and the Tragedy of Soviet Science

- In this book, Dr. Valery Soyfer, a former Soviet scientist who had met Lysenko, documents the destruction of science and scientists under the influence of Lysenko. Contrary to numerous opinions, Lysenko was an poorly educated agronomist who happened to have been in the right place at the right time. His peasant upbringing and miraculous findings–never empirically proven or duplicated–made him a star proletarian scientist, the kind needed to bring about true Communism. Along his way to the top, he was assisted by many people who thought him a sincere scientist; he later had many of these people purged after gaining the almost total support of Stalin and Khrushchev. Whether to propel himself upward, to bring down the academics he detested, or to protect himself, Lysenko nearly eliminated all serious work in genetics, agriculture, and biology from the 1930s into the 1960s, bringing repercussions all the way to the 1990s.

- Soyfer, Valery. Lysenko and the Tragedy of Soviet Science. New Brunswick, N.J.: Rutgers University Press, 1994.

Criticism and Dissidence in the Scientific Community

The Medvedev Papers

- This book includes two of the works of Zhores Medvedev, biologist and historia, which he wrote between 1968 and 1970. It includes Fruitful Meetings Between Scientists of the World and Secrecy of Correspondence is Guaranteed by Law. They were originally distributed through samizdat, and latter published in 1971 as The Medvedev Papers in London. His works criticize the inability of scientists to communicate with other scholars in the outside world, in addition to denouncing postal censorship in the Soviet Union. For this, he was arrested and forced detention in the Kaluga psychiatric hospital in May 1970. However, this action produced many protests from prominent scientists.

- Medvedev, Zhores A., and Vera Rich, trans. The Medvedev Papers. London: Macmillan, 1971.

Manipulated Science

- In this book, Popovsky puts together microfilmed diaries and notes, interviews with scores of scientists, and accounts of life at the special science cities and the many Institutes, secret and otherwise, spread throughout the country. He stresses that the very idea of a “Soviet” science is parallel to the spirit of an independent, dispassionate, cooperative, and democratic search for truth. In addition, Popovsky becomes very critical of a government that rules a population largely made up of party members and bureaucrats, of barely literate ethnic groups in the republics, and of inferior technicians who were given favored placements because they represented peasants or workers or the party faithful. On the other hand, the scientists suffer death, exile, imprisonment. He also discusses an ever-rising anti-Semitism that hinders the scientific community.

- Popovsky, Mark Aleksandrovich.Manipulated Science: the Crisis of Science and Scientists in the Soviet Union Today. New York: Doubleday, 1979.

Marxism and Science

This section attempts to cover works that discuss Marxism and science as ideologies and ways of thinking and analyzing. A trend emerges: a scientific way of thinking is not necessarily a Marxist (or, much possibly, a State) way of thinking.

The Communist Party and Soviet Science

- In this book, Fortescue uses theoretical models of totalitarianism, pluralist and vanguardist models in an attempt to explain the inner workings of science in the USSR. It is a good book to introduce oneself into the world of State-controlled scientific research, social and party advancement, and publishing. He shows the disparity between Marxist philosophy and the “ethos of science”. In addition, the author portrays a Party that practically butchered scientific progress for decades.

- Fortescue, Stephen. The Communist Party and Soviet Science. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1986.

Marxism and Contemporary Science

- Lindsay shows the other side of the coin in this book. Here, one can find a piece of work that attempts to redefine Marxism and rescue its teachings from newer interpretations. For Lindsay, Marxism and science can coexist and work together to further progress.

- Lindsay, Jack. Marxism and Contemporary Science, or The Fullness of Life.. London: D. Dobson, 1949.

The Marxist Philosophy and the Sciences

- This books compiles Haldane’s reflections on natural and social sciences from his perspective as a recently “converted” Marxist. Like Lidnsay (above), the author mixes Marxism and Science, while discussing different disciplines –mathematics, quantum theory, biology, chemistry, psychology, sociology, and cosmology.

- Haldane, J. B. S.. The Marxist Philosophy and the Sciences. 1939. Reprint, New York: Random House, 1969.

Marxism and Science: Analysis of an Obsession

- This book is concerned with the idea of Marxism as a science. It performs a thorough analysis of the claim, first made by Marx and Engels themselves, that Marxism is some kind of “hard” natural science of society able to identify laws of social development and to provide a scientific guide to revolutionary activity. In addition, this book uses Wittgensteinian analysis of Marxist discourse to construct a totally different conception of Marxism appropriate to the postmodern world. In this conception, Marxism is a point of view that can be advanced, rationally defended, and made convincing and persuasive to others, but that is as partial in some respects as any other political point of view. Thus, to reconstruct Marxism requires not only understanding language in a different non-objectivist way but also adopting a new political practice and program, which the book proceeds to outline.

- Kitching, Gavin. Marxism and Science: Analysis of an Obsession. University Park, Pa.: Pennsylvania State University Press, 1994.

Soviet Science Fiction

Red Stars: Political Aspects of Soviet Science Fiction

- McGuire, Patrick L.. Red Stars: Political Aspects of Soviet Science Fiction. Ann Arbor, Mich.: UMI Research Press, 1985.

Three Tomorrows: American, British, and Soviet Science Fiction

- Griffiths, John Charles. Three Tomorrows: American, British, and Soviet Science Fiction. Totowa, N.J.: Barnes & Noble Books, 1980.

Further Reading

http://web.mit.edu/slava/guide/Biblio/5.htm

http://web.mit.edu/slava/guide/Biblio/6.htm#space

http://www.youtube.com/user/mosfilm?feature=watch