Suk-Young Kim

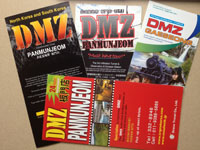

The Korean Demilitarized Zone (DMZ), a small strip of land only two miles wide

The Korean Demilitarized Zone (DMZ), a small strip of land only two miles wide

and 155 miles long, is surely one of the most paradoxical places on earth. Conceived as a buffer zone, the DMZ was intended to bring about a temporary ceasefire between the two Koreas in 1953. The result of a bloody civil war, the DMZ is still littered with active landmines and the ossified remains of war casualties. Paradoxically, however, since the ceasefire this silent “no man’s land” has had an aura of pacifism and environmentalism. The DMZ provides an ecological for many endangered natural species amidst the highly industrialized Korean peninsula.

This paper explores these contradictory impulses that make the Korean DMZ a unique tourist attraction. A perennial destination for separated families living in South Korea who see the place as the closest approximation of their lost hometown in the North, the DMZ is also a staple site in the itinerary of foreign visitors who seem to be primarily attracted by its significance as the last bitter outpost of the Cold War era. If one nation’s trauma is the primary force for attracting local and global visitors, how does it upset the conventional notion of mass tourism as a way to encourage pleasure and leisure? If the element of consumptive desire should be rectified in DMZ tourist discourse, then what alternative rhetoric fills that gap? I attempt to tease out the ways in which global and local tourists claim this unique geopolitical biosphere by taking a closer look at the much contested perspectives championing the ecological value of the DMZ and the local anxiety to remedy national trauma through its eventual abolition.