Since taking his first foray into seriousness with Annie Hall in 1977, Woody Allen has been nothing if not upsetting, morally and emotionally. His earliest films were one laugh riot after another—ingenious, cheeky, odd—but he really hit his stride when he embraced his inner Ingmar Bergman in the late 1970s and beyond, asking the Big Questions with an uncommon, mature solemnity. Manhattan surveyed the emotional wreckage of a man whose wife left him for another woman. Crimes and Misdemeanors implied that murder was an acceptable solution to a mistress problem. Match Point argued that morality is meaningless in a world dominated by luck and happenstance.

Since taking his first foray into seriousness with Annie Hall in 1977, Woody Allen has been nothing if not upsetting, morally and emotionally. His earliest films were one laugh riot after another—ingenious, cheeky, odd—but he really hit his stride when he embraced his inner Ingmar Bergman in the late 1970s and beyond, asking the Big Questions with an uncommon, mature solemnity. Manhattan surveyed the emotional wreckage of a man whose wife left him for another woman. Crimes and Misdemeanors implied that murder was an acceptable solution to a mistress problem. Match Point argued that morality is meaningless in a world dominated by luck and happenstance.

These one-line synopses are deceptive, however, because they suggest Allen’s serious projects are devoid of his legendary humor. They are not. To see a Woody Allen production is not to choose between comedy and tragedy, and his collected works are not so easily divided into categories as are, for example, William Shakespeare’s. Unlike Bergman, whose films have almost no humor at all—perhaps that’s the reason some are considered “dated” in today’s irony-strewn culture—Allen sees comedy and tragedy as the yin and yang of life. Film, which reflects life, should contain both.

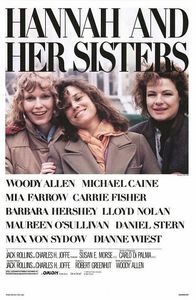

Accordingly, I offer 1986’s Hannah and Her Sisters as the best movie Woody Allen has ever made, due in large part to its understanding of that very fact. Amongst an enormous and distinguished cast, it is Allen himself who is involved in the film’s key scene.

As Mickey Sachs—a screen variation of Allen’s own persona, as ever—Allen plays a TV producer paralyzed with fear about his own mortality. Called simply, “The hypochondriac,” worried that the fact of death renders life meaningless, Mickey embarks on a hapless odyssey through New York to find an answer that might put his mind at ease. He tries religion—his own, Judaism, has long failed him—then calls upon the likes of Plato and Freud, but nothing lifts his spirits. He’s too clever and pessimistic.

Finally, Mickey has a breakthrough, and the way it comes about shows Allen’s knack for blending tragedy with comedy. Following a failed suicide attempt—the rifle slides off his forehead because he is sweating so much—Mickey escapes his apartment, takes a long walk and eventually wanders into an art house theater, which happens to be showing the great Marx Brothers farce Duck Soup. In voiceover narration, Mickey describes watching the film—“I had seen it many times as a kid and always loved it”—with new eyes. How dare he despair, he hears himself say, when life offers such treasures as Groucho Marx? Mickey’s life improves immeasurably from this point onward.

Is this a cop-out? Hannah and Her Sisters has been noted—and faulted, by some—as being Allen’s only “serious” film with a happy ending. In his New York Times review, Vincent Canby described the movie as “warmhearted,” which is indeed a characteristic that often eludes Allen’s work, even when successful. It is noteworthy that Allen’s two biggest idols and influences—Ingmar Bergman and Groucho Marx—are as far removed from each other, thematically, as can be. Bergman stands as a modern monument to tragedy, while Marx’s career was a zenith in American comedy.

Yet both men inhabited the same world—simultaneously, for 59 years—and were able to reach audiences who enjoyed them both. That the ideas and ideals of both men could be merged into one is a tribute to Hannah and Her Sisters as a film, to Woody Allen as a filmmaker and to the much larger truth that comedy and tragedy are two sides of the same coin.

-Dan Seliber