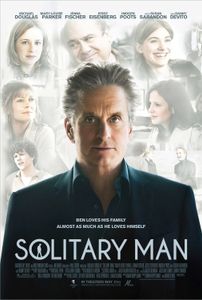

The title “Solitary Man” sounds a bit like “A Serious Man,” but the two movies are polar opposites. Whereas the Coen brothers’ film is about a good man struggling to keep his life in balance, the 2009 film by Brian Koppelman and David Levien concerns a bad man resolutely tearing his life apart. More importantly, A Serious Man is odd, scary, and philosophically ambitious; Solitary Man seeks nothing better than to titillate people who find Michael Douglas totally fascinating. If this sounds like an exaggeration, go see the film and count how many monologues the script spoon-feeds its star. Consider the midfilm monologue, delivered to the unfortunate Jesse Eisenberg, that begins something like “Lemme tell you a story” and then continues for a good two minutes without a single cutaway for relief. Eisenberg may have been grateful for the lack of a reaction shot, which would have forced him to feign interest. In that sense, he’s luckier than Susan Sarandon, Danny Devito and all the other co-stars crammed into the film just to ask Douglas helpful questions.

The title “Solitary Man” sounds a bit like “A Serious Man,” but the two movies are polar opposites. Whereas the Coen brothers’ film is about a good man struggling to keep his life in balance, the 2009 film by Brian Koppelman and David Levien concerns a bad man resolutely tearing his life apart. More importantly, A Serious Man is odd, scary, and philosophically ambitious; Solitary Man seeks nothing better than to titillate people who find Michael Douglas totally fascinating. If this sounds like an exaggeration, go see the film and count how many monologues the script spoon-feeds its star. Consider the midfilm monologue, delivered to the unfortunate Jesse Eisenberg, that begins something like “Lemme tell you a story” and then continues for a good two minutes without a single cutaway for relief. Eisenberg may have been grateful for the lack of a reaction shot, which would have forced him to feign interest. In that sense, he’s luckier than Susan Sarandon, Danny Devito and all the other co-stars crammed into the film just to ask Douglas helpful questions.

The solitary man is Ben Kalmen, a disgraced former auto dealership CEO addicted to sex, sometimes with girls hardly out of high school (though to be fair, he’s not too picky for a one-night stand with a woman just over half his age). We don’t see Ben in his big shot years or during the scandal that ruined him. Instead we get a brief prologue set six years before the start of the film that shows a still-successful Ben receiving iffy results on his EKG, and then we skip all the interesting stuff to catch up with him as a completely mediocre sexagenarian trying to restart his career. Ben is clearly meant to be a ruthless old lion, able to ensnare brassy young women thanks to a life of sexual fine-tuning. Instead, he’s more reminiscent of a good-natured but slightly dim uncle whose feelings you don’t want to hurt.

This is a problem for the plot, which requires Ben to bed Allyson, his girlfriend’s snotty daughter, while he takes her to meet the dean of his old college in Boston. Lecturing her on how get a man to give her pleasure, he has all the tantalizing allure of a high school sex ed instructor. I didn’t actually realize I was watching a seduction scene until the jump cut to Imogen Poots and Douglas frantically slurping each others’ faces–a transition that provoked howls of “What??!” from the audience. Poots had more chemistry with pretty much every other actor who shared a scene with her. Watching her get steamy with Danny Devito would have been less shocking.

While on campus, the old lion also gets his claws into college boy Cheston (Eisenberg) as a way of reliving his own youth. Having won the young man’s affection by barking at him, “You don’t get laid much, do you?”, Ben tutors him in matters of the heart. Naturally, Cheston worships his failed-car-salesman mentor and takes him to hip college parties where background extras drink beer and pump their fists for no reason and nothing happens–except for monologues, of course.

Of course, Ben’s fling doesn’t stay a secret. Allyson herself declares it to her mother in a fit of pique. Suddenly, Ben’s new business venture tanks and everyone recognizes him for the aging sociopath Douglas is supposed to embody. I’m being harsh on the star, but the script is even crueler; it gives him no real chance to develop, only conflicts with characters who appear for one scene just to be nuisances. By the time Susan Sarandon reappears as his ex-wife and prompts him to explain his infidelity in detail (spoiler: it’s because he was afraid of death!), it’s clear that the screenwriters are in thrall to Ben. They don’t write interactions: they throw characters at Ben so that he can show what a sad jerk he is.

There is one exception: Ben’s relationship with his sweet daughter Susan, played by Jenna Fischer, who doesn’t even object when he forbids her to call him “Dad” in public. Fischer portrays Susan’s love and long-suppressed anger quite well, and Douglas is touching when he finally admits his loneliness to her. If the filmmakers had given more screen time to Susan and less to Ben, they would perhaps have avoided the impression of simply humoring the man’s egomania. Meanwhile, there are better films about midlife existential crisis. Not all of them treat their protagonists as “solitary men.”

-Julia Zelman