One of the few things even resembling a consensus that you will find among film fans is that Claire Denis is the best working female director. Whether she is the greatest female filmmaker of all time or the finest working director period are both up for debate (for the record, I’d say she’s pretty high up there in both categories). This consensus comes from a remarkable mixture of genre-bending narrative experiments, her ability to create profound beauty out of the smallest detail and intensely personal stories told in very personal ways. One of her recurring personal stories is that of the colonial experience in Africa. She was born in France, but spent her entire childhood moving around French colonial Africa with her family. Her first film, 1988’s Chocolate, was an autobiographical study of her own childhood experiences during the end of colonialism. She’s returned to the continent every few years during her career, with 1999’s masterful Beau Travail using Melville’s novella Billy Budd as a basis for a study of masculinity and the role of the post-colonial force. White Material is different. In those films, the relationship between the natives and the colonial/post-colonial forces was strained but reasonably peaceful. Now, nearly fifty years since the end of colonialism, it is time for the entitled to leave a place that they do not understand. Most of the white characters in the film claim to be African, and some go so far as to insult other French citizens, but they are not a part of the land. In her other films, the characters are a part of their environment—in Friday Night the young couple is as much a piece of the film’s central traffic jam as any of the cars and in Beau Travail the soldiers are as much a part of the desert as any natives—but in White Material the characters do not belong, despite their beliefs to the contrary, and this conflict is what carries the film.

One of the few things even resembling a consensus that you will find among film fans is that Claire Denis is the best working female director. Whether she is the greatest female filmmaker of all time or the finest working director period are both up for debate (for the record, I’d say she’s pretty high up there in both categories). This consensus comes from a remarkable mixture of genre-bending narrative experiments, her ability to create profound beauty out of the smallest detail and intensely personal stories told in very personal ways. One of her recurring personal stories is that of the colonial experience in Africa. She was born in France, but spent her entire childhood moving around French colonial Africa with her family. Her first film, 1988’s Chocolate, was an autobiographical study of her own childhood experiences during the end of colonialism. She’s returned to the continent every few years during her career, with 1999’s masterful Beau Travail using Melville’s novella Billy Budd as a basis for a study of masculinity and the role of the post-colonial force. White Material is different. In those films, the relationship between the natives and the colonial/post-colonial forces was strained but reasonably peaceful. Now, nearly fifty years since the end of colonialism, it is time for the entitled to leave a place that they do not understand. Most of the white characters in the film claim to be African, and some go so far as to insult other French citizens, but they are not a part of the land. In her other films, the characters are a part of their environment—in Friday Night the young couple is as much a piece of the film’s central traffic jam as any of the cars and in Beau Travail the soldiers are as much a part of the desert as any natives—but in White Material the characters do not belong, despite their beliefs to the contrary, and this conflict is what carries the film.

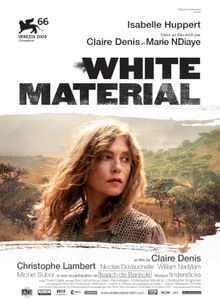

Maria Vial (Isabelle Huppert in a magnificent performance) co-owns a coffee plantation in an unnamed African nation with her ex-husband Andre (Christopher Lambert). His father formerly owned the place and still lives there, floating around as a symbol of a colonial past. Their idle adult son Manuel (Nicolas Duvauchelle) sits in his bed all day and rarely helps with the harvest while Andre’s second wife and son judge his laziness. The story is told in jumbled flashbacks (although it is still a very straightforward story, especially when compared to her L’Intrus), but it begins with soldiers from the army hunting down a rebel leader called “The Boxer” (Isaach De Bankole), who crawls to the plantation with a wound he knows will be mortal in order to die in peace and avoid the mass of child soldiers who try to follow him. As the conflict between the rebels and the army escalates, anyone with money is told to leave the country, but Maria does not listen. Her latest harvest is nearly complete and she does not believe that the fighting is close. Eventually, this disbelief devolves into a full psychosis as she ignores all evidence of the conflict because her sense of entitlement to the land will not allow her to leave, even as Manuel snaps after being attacked by two child soldiers and decides to join the rebels. Maria tries to rationalize her decision by forcing herself to believe that she is as much of an African as the common people who she hires to finish the harvest. In the hands of a lesser director, this could have easily become an action film about one woman trying to defend her way of life, but Denis’s films have always avoided an easily applicable genre. Friday Night could have been a simple love story and Beau Travail could have been a war movie, but in her able hand they could transcend the silly bonds of genre and become far more profound studies of humanity, which is exactly what happens in White Material.

For me, the most interesting story is Manuel’s. Denis uses him as a metaphor for two seemingly incompatible things. On the surface, he is the white man in Africa personified. At one point he goes so far as to cut off his blonde hair and shove it down the throat of a black friend. He is lazy and violent and he does not have anything even resembling an understanding of what it is to be poor and under the control of Europeans. He gives the rebels guns and food and medicine, but forces the young soldiers to use them incorrectly, to solve his problems. Conversely, his story also seems to model the western view of black Africa. For the first half of the film, he is constantly mentioned but never actually seen. The characters refer to him as a lazy child, but he is an adult with the potential to do more, but with no opportunity. When he finally leaves the house, his mother ignores his absence at first and then cries, but does not act, when it becomes clear how broken he has become. This seems to echo the relationship between the colonial powers and Africa very well, and is the closest thing to a real political statement that you will find in a Claire Denis film. She places most of the blame for Manuel’s action on his mother, and thus blames Europe for the demise of Africa.

This is the first film Denis has made without her longtime cinematographer Agnes Godard since 1990’s No Fear, No Sleep, and while replacement Yves Cape does an excellent job in his own right, White Material isn’t quite as gorgeous as Denis’ last few films. There is no moment with the aching beauty of the dance sequence in 35 Shots Of Rum, which topped more than a few lists of the best moments in film from last year. Denis’s signature has always been to frame the scene in a carefully composed long shot with few cuts before a quick close-up of a part of a character’s body, like a cheek or a hand, and there isn’t as much of that second part here, but the long shots are just as beautiful as ever. Unlike Hollywood message movies set on the continent, there is a great degree of reality in White Material. Her films are all about sensation, and she does a beautiful job of capturing the sensation of her Africa. The score, which moves between ambient post-rock and more traditional African music captures the mood of an outsider trying to get in, but most of the sensation is captured visually. Both the beauty of the land and the brutality of the situation are allowed enough screen time to make her point. There is a way for the wealthy to help, but they must stop old patterns of behavior. The most sensible person in the films seems to be The Boxer, who just wants to die in peace, but that peace brings hell onto every other character, and Denis know that the same result will come if Africa allows itself to die. It is difficult to imagine human beings living in the conditions shown in the film, but Denis wants to remind us of that part of the world, and she wants to show us that we must offer unconditional help, not control.

-Adam Burnstine

White Material is unrated, but it does feature violence and nudity.

It will play at the Boston museum of fine arts on Saturday July 17th at 8:20 as a part of the Boston French Film Festival.

Directed by Claire Denis; written by Claire Denis and Marie N’Diaye; director of photography, Yves Cape; edited by Guy Lecorne; original music by Stuart Staples; production designer, Abiassi Sainte-Pere; produced by Pascal Carcheteux, distributed by IFC. Running time 1 hour 46 minutes.

One Comment

Julia posted on July 19, 2010 at 10:53 pm

I saw this at the (completely packed!) screening at the MFA French film fest. The scenes with the child militia were incredibly disturbing in their unsensational way. I didn’t quite understand the very end, namely Maria’s final action. It seemed symbolically appropriate but not totally comprehensible in terms of the character. Still, the best film the three very good ones I’ve seen at the French Film Festival.