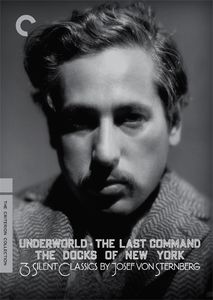

A few weeks ago, Criterion released an excellent box set–a collection of early Josef von Sternberg films. They are a must own for anyone interested in cinema, especially in this new incarnation. The set contains commentaries, documentaries, essays, and two brand new scores from the Alloy Orchestra. I had the opportunity to catch up with Ken Winokur about their contribution to the films, what they’ve been working on, and what’s next.

A few weeks ago, Criterion released an excellent box set–a collection of early Josef von Sternberg films. They are a must own for anyone interested in cinema, especially in this new incarnation. The set contains commentaries, documentaries, essays, and two brand new scores from the Alloy Orchestra. I had the opportunity to catch up with Ken Winokur about their contribution to the films, what they’ve been working on, and what’s next.

-Rob Ribera

1. How did the Alloy Orchestra get involved in the project?

I was talking to Barry Allen at Paramount about working with a different Paramount film Beggars of Life, and he mentioned that they had some other films, including Underworld and suggested that we might want to consider them. I was familiar with Underworld and immediately jumped on the idea. I called the NY Film Festival and set up a show within 20 minutes.

2. What was the process for restoring the print of the Last Command with Paramount? Why this film?

I don’t know anything about the restoration. They made a new print for us to use, but it was off an existing negative.

3. Were there any music cues already available for these two films (like for Man with a Movie Camera or Metropolis)?

Only the Russian national anthem which we used in Last Command. We did a little research to make sure we were using the correct one (there were many).

4. How to you incorporate these cues when they exist already into your own style?

We took that cue (which we found on the web) and translated it from an orchestral score to a piano score with percussion. Not a very big change, but since there was a piano player on screen, we needed to match the sound.

5. Do you try to make any references to previous material?

No, we start fresh with every film, and don’t reference original scores that might be available.

6. Your type of music is very unique, is it sometimes difficult to match up to certain films?

We adjust our style to the film. There’s almost no similarity between our Metropolis score and Underworld. Chang is mostly percussion and sounds like a traditional Thai music group. But, the really subtle films, which require a very quiet and melodic score, can be difficult for us. The two percussionists have to be extremely restrained, and more than not we end up playing our second instruments (accordion and clarinet) instead of percussion.

7. Where do you find the objects you use? What is the most unique “instrument” that you get to bang on or get to make noise during a concert?

I’ve been collecting objects for over 30 years. We have quite a storehouse of stuff at this point. We went to junkyards for a while and got a large amount of stuff. The horseshoes were sent to me by my wife from a trip to New Mexico. One of the bells we use, was sent to me by my Mom from a trip to Japan. The bedpan, which replaces an older one that got too smashed up, was liberated from a closet at Mass General Hospital. The pans we have on the tabletop were part of a plate storage table from a restaurant that Terry brought home when they were throwing them out. The bent metal sheet was found on the streets of NY during our dinner break before a show. The objects wait for us, we just bring them to their proper home.

8. How does it feel to add a new layer of experience to what is considered the first gangster film?

We love Underworld. It’s a film that I had earmarked a decade ago as one that would be nice to score. We were really excited when it became available through Paramount. It’s a style that comes quite naturally to us. We always seem to gravitate to the darker films, and especially ones that have a modern sense of the ambiguity of the difference between good and evil. Hitchcock’s Blackmail is another example of this. It’s funny, but audiences all seem to relate to the gangster myth, and Alloy is no different. The gangster is the ultimate outsider. In Underworld, he is a crook and ultimately a killer, but he’s also a Godfather figure – taking care of his community and acting as an alternate authority to the cops and government.

9. Emil Jannings has such an incredible screen presence. His acting clearly tries to compensate for the lack of dialogue–how did you adjust to that when creating the score?

We always gravitate to dramatic (as I was saying about Underworld). It’s just the nature of the styles of music that we enjoy. Our music is bold, and it fits well to the bold acting of Emil Jannings

10. You’ve recently re-scored Metropolis after the discovery of even more lost material–what was it like to revisit the film? Did you need to come up with entirely new cues for some characters that have more prominence now?

My first response was, “Not again.” We had done something like 500 performances of the previous versions, and had stopped doing Metropolis. We hadn’t rewritten our score to go with the last version, and because of copyright issues, we couldn’t use the previous versions we already knew. But once it sunk in that this was going to be restored and put out, and after I found that we were going to be allowed to work with the new restoration, my response was, “Oh god, this is going to be miserably long and boring.”

It wasn’t until we had our first rehearsal that my attitude changed. The first run through was so much fun! Most of our scores are so restrained comparatively, that it was really a gas to be doing all that up tempo drumming again.

Although I got the sense from our rehearsals that the new cut of the film worked much better than the old ones, it wasn’t until the first performance, where I could see the audience response, that I could really tell that the new cut is so much more satisfying to the audience. The continuity is restored and the editing has dramatically improved the timing.

It’s also clear to me that our new arrangement of our score is vastly better than the old ones. Because the score was originally written very quickly, and contained lots of improvisations, there were lots of sections that weren’t finished or perfected. Taking the score back into the studio and really examining every cue, writing new material, and reworking the old ones really led to a much tighter and more suitable accompaniment.

We wrote a couple new themes (one for the Thin Man) that are quite nice. They are related to previous themes (like the mane theme) bit are new tunes. Mostly, though we just added bits and pieces to the previous themes. Every cue took a step forward in complexity and sophistication – making them more satisfying as compositions and helping the ebb and flow of the film.

11. How long does it usually take to finish a score–how long did these two take and what is the process?

We usually spend a year or so picking a film. Then I watch it a bunch of times and write up a storyboard of the scenes, along with the timings. We transfer the film to our computer. Then we go through the film scene by scene and improvise ideas, recording everything in sync on the computer. When we have an idea we like, we move on to the next scene. After that, it takes 2 – 3 months of composing and rehearsal. We continually refine the score throughout the rehearsal period, so there’s really no end of the composition period. When we get to the end, we back up and start over again, listening to what we’ve recorded and make improvements. We do that again and again until we’re satisfied with our score. We even continue to refine the score throughout the performances for years.

12. I’m also interested to know who you eventually would have to submit your music to, since there is no director to work with.

We are beholding to no one, and don’t need to get approval from anyone. We used to do test screenings, but didn’t ultimately find them very useful. Everybody had a different opinion about what worked best and what they would change. Since there are 3 of us, we find that we are our own best critics. I think that’s one of the strengths of composing collaboratively and not just relying one a single “genius” composer.

13. How would you compare your live shows and working in the studio for a DVD release?

There’s not much difference, except we can stop and do something over again. Sometimes we record the whole score in a single take or two (as we did with Underworld). Sometimes we do it scene by scene (like Last Command).

14. Who are the film composers you admire? Who do you think is doing the most interesting work today?

I can name some names (Danny Elfman, Bernard Herrmann, Nino Rota) but I really don’t listen that much to other film composers. Because of our odd instrumentation, there’s no real possibility to take much from other composers.

15. What are you working on next?

Don’t know.

16. What are some films that you’d like to write music for in the future?

Son of the Sheik, Variety, Ship of Lost Men, Beau Gest – there are many, but many have issues with copyright or access to the prints.

17. You’ll be performing at BU in November, what can the audience expect from your Nosferatu score?

Obviously, this one skews toward the creepy. There’s an interesting combination of seductive melodies and some of the most discordant “tunes” we do. There’s a lot of outright noise (particularly from the “column”—an air conditioning ductwork that makes a horrific screeching noise that we use for the ghoul himself.