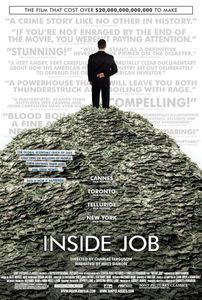

CDOs. AAA ratings. Derivatives. These are just a few financial phrases that Matt Damon simplifies for audiences of average Americans in Charles Ferguson’s documentary Inside Job. The film carefully walks the line between cinema and power point presentation as it attempts to explain the 2008 economic crisis and—more importantly—point the finger of blame. Ferguson (No End in Sight) is bold and ambitious, opening his film with the daring statement: “This is how it happened.” With such a claim, Inside Job opens itself to sharp criticism and debate, but this only comes from the Wall Street Wiseguys that the film blames for the current economic situation. The documentary proves to be a comprehensive, although essayistic, account of the financial crisis.

CDOs. AAA ratings. Derivatives. These are just a few financial phrases that Matt Damon simplifies for audiences of average Americans in Charles Ferguson’s documentary Inside Job. The film carefully walks the line between cinema and power point presentation as it attempts to explain the 2008 economic crisis and—more importantly—point the finger of blame. Ferguson (No End in Sight) is bold and ambitious, opening his film with the daring statement: “This is how it happened.” With such a claim, Inside Job opens itself to sharp criticism and debate, but this only comes from the Wall Street Wiseguys that the film blames for the current economic situation. The documentary proves to be a comprehensive, although essayistic, account of the financial crisis.

Ferguson neatly organizes his film into five parts, each presenting one aspect of the economic breakdown, as if writing a thesis paper. While this contributes to the film’s pedagogical tone (think college Economics 101 lecture), the film’s style is extremely practical when explaining complex financial terms to an audience who may have never had an economics course or (let’s be honest) probably slept through it in college. Damon’s narration makes the technical terms more easily digestible, and the graphics and flow charts give us something to look at as we pretend that Jason Bourne actually understands the phrases he is describing (it becomes clear early on that Damon is just a name to associate with the film, neither a character nor a commentator). The interviews with various figures from the worlds of Wall Street and financial consulting sufficiently introduce us to our cast of heroes and villains. The more expensive the suit, the more evil the man. Those who refuse to participate in an interview are the guiltiest of all.

Despite these clichés of the documentary conventions, Inside Job does an admirable and refreshing job of remaining politically neutral—Ferguson blames all presidential administrations for their passivity regarding the nation’s economy. Instead, the director faults a “Wall Street Government” for neglecting to hold America’s financial interests at heart, explaining that every administration from Reagan to Obama has appointed financial felons to high government positions. This move on Ferguson’s part allows us to look beyond anti-conservative or anti-liberal sentiments and focus on the larger issue: the corruption of Wall Street.

Ferguson seems to enjoy detailing the scandals of Wall Street bankers a bit too much, including montages of fraud and money laundering, as well as testimony from a New York prostitute who claims to have faked (wait for it) invoices for some of the top investment bankers in the industry. One of the more interesting interviews is with a therapist, who also claims to have high-ranking investment bankers as clients, which calls attention to the psychology of Wall Street bankers (so greed is a mental illness now?). But despite the shocking interviews and staggering figures, the documentary lacks one very important ingredient: a victim.

Arguably, Ferguson intended for us to see ourselves as the victims, losing our homes, pensions, and lunch money to the Wall Street bullies. However, the average American citizen receives hardly any screen time. Besides numerous shots of foreclosed homes and a brief interview with a Tent City resident, the film denies us a character to play the role of representative. In an interesting decision, Ferguson interviews a non-English-speaking immigrant to relate her own story of foreclosure and victimization. While we sympathize with her situation, she is not exactly the illustration of the typical American citizen, and the film carries our thoughts to other hot-button issues, which certainly is not the director’s intention. Instead, a more relatable “character” would have made the film more personal and emotional, a pleasant change from the informative, yet dull, facts and figures that dominate the documentary.

Ultimately, Inside Job does not motivate audiences to write their Congressmen or protest in Washington D.C. Moreover, the documentary does little in the way of offering resolutions; Ferguson is suddenly vague in this department, even though I doubt anyone truly expects him to singlehandedly solve the economic crisis. Ferguson’s decision to omit thoughtful suggestions for financial repair prevents the film from transcending from rant session to moving documentary cinema. Still, the pleasure (if one could call it that) in viewing Inside Job is in screening the documentary in a theater setting. There is something reassuring about tsking, nodding, and sighing as a collective that makes me feel as if debt and unemployment are not in my near future. But, as Misters Bernanke, Paulson, and Summers demonstrate, maybe I should get a job on Wall Street to avoid these economic threats instead.

Directed by Charles Ferguson; written by Chad Beck and Adam Bolt; director of photography, Svetlana Cyetko and Kalyanee Mam; edited by Chad Beck and Adam Bolt; original music by Alex Heffes; produced by Charles Ferguson, Jeffrey Lurie, Kalyanee Mam, Audrey Marrs, Anna Moot-Levin, and Christina Weiss Lurie; released by Sony Pictures Classics.

Review by Melissa Cleary