UFOs over Colorado!!!

Hat tip and discussion:Bad Astronomy.

Nov

28

Nov

24

Scientific American has an important article on "How Drug Company Money Is Undermining Science: The pharmaceutical industry funnels money to prominent scientists who are doing research that affects its products--and nobody can stop it"

Nov

24

Science denial: a guide for scientists (pdf) by Josh Rosenau.

And, a bonus pie chart from Desmogblog

Nov

23

How much sea ice is there?

The most commonly discussed measure is the extent of sea ice in the arctic. This is used mostly because it is easier to measure precisely.

However, one downside of measuring extent is that it's not easy to get a feel for what's really happening with the loss of arctic sea ice.

Each winter the arctic freezes over, and the the extent returns more-or-less to "normal."

In the summer, the minimum extent gives a fairly good indication of how much ice we're losing, but even there, things bounce around quite a bit, as we can see on the following graph from the Arctic Sea-Ice Monitor page.

One gets a better sense of the fairly steady loss of ice over the past decades by looking instead at sea ice volume. This takes into account the thickness of the ice and the fact that even though the arctic refreezes each winter, the resulting ice is thin and will melt more quickly in the summer.

Here's a nice animated graph of the decrease in sea ice volume.

Nov

12

Nov

5

Who cares about Randi's $1 million for evidence of paranormal activity? Now you can get $10 million, just for flushing out Big Foot. See here.

Shouldn't be too hard. After all, someone bumped into one in Washington not long ago:

(Huffington Post has a helpful slideshow of Bigfoot pictures.)

Also, be careful with your Bigfoot hoaxing. It's a lot less amusing when it ends up with someone getting killed.

Update: Another story on big foot in Slate here.

Nov

4

Nov

2

Cherry picking is the fallacy of selecting a small subset of data that supports your thesis while ignoring other data that undermines it.

This is a fallacy because for just about any claim one can always find a small amount of data that can be viewed as supporting that claim. A reasonable assessment of the evidence requires us to look at all the data available, and to make sure that we are not biased in choosing which data we present.

As an example, consider the following claim from a 2009 paper by ex-senator Harrison Schmitt:

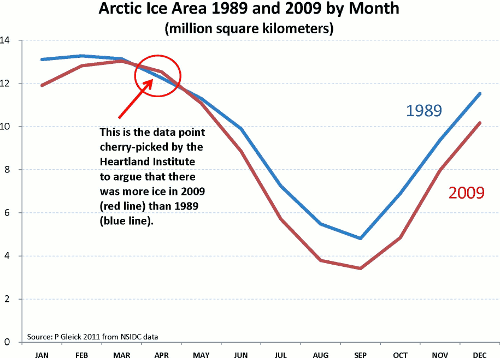

"Artic [sic] sea ice has returned to 1989 levels of coverage."

Now this claim (along with many others in the paper) was clearly wrong. Many experts (and non-experts) pointed out that sea ice levels in 1989 significantly exceeded those in 2009.

Joseph Bast, president of The Heartland Institute, wrote in and demanded an apology for this criticism:

"Boslough falsely accuses Harrison Schmitt of making a false statement in 2009 about Arctic sea ice having returned to 1989 levels, and then failing to correct the error. In fact, National Snow and Ice Data Center records show conclusively that in April 2009, Arctic sea ice extent had indeed returned to and surpassed 1989 levels."

This is our example of cherry picking. It is technically true that in April of 2009, ice extent exceeded the ice extent of the same date in 1989. But it is false to suggest that this implies that Schmitt was correct when he claimed in 2009 that "sea ice has returned to 1989 levels."

Peter Gleick explains why with the following graph:

Schmitt's claim was that the ice area in 2009 (the red line) was greater than in 1989 (the blue line). A glance at the graph shows that this is clearly false.

What Bast has done is pick out a single tiny bit of data (a "cherry") that, in isolation, could be viewed as supporting Schmitt's claim. But this obviously nothing but fallacious misdirection.

I present this example because it's so egregious that it makes the nature of the fallacy plain. But in many cases it might not be immediately clear whether the data in question is cherry-picked or not.

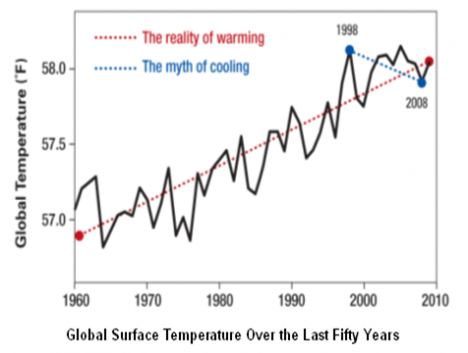

A few years ago it was popular for climate-change deniers to argue that global warming had stopped and that the world was now cooling. One would frequently encounter graphs like the one to the right.

A few years ago it was popular for climate-change deniers to argue that global warming had stopped and that the world was now cooling. One would frequently encounter graphs like the one to the right.

It certainly looks like temperatures are on the way down, doesn't it? Why, then, should we be concerned with increased CO2? It looks like the alarmism of the climate scientists has been debunked.

But these sort of arguments ignore two important facts:

1) Climate change is a long-term effect. In order to see global warming, you need to look at temperature trends over decades, not over single years.

There will be a good deal of year-to-year variation, but (according to the scientists) over the long run those fluctuations will get higher and higher. We'll have more high-temperature years, and we'll break records on the high end, and we'll have fewer low-temperature years. But nobody expects a steady march of each year being warmer than the last.

2) 1998 was an unusually warm year. This remarkable spike in temperatures was only partly due to the long-term global-warming trend however. Added to that general trend was an upward spike in the usual year-to-year variation in temperatures, due to a particularly strong El Nino event.

This means that if you you start your graph from this particularly hot year, it will seem that things are cooling down. But really the world is still steadily warming, and you've just cherry picked some data to make it seem otherwise. The following graph shows what's really going on:

---UPDATE----(4/16/13)----

It never gets old, aparently. Tamino catches Lawrence Solomon (author of a collection of biographies of deniers) engaging in another world-class case of cherry picking at the Financial Post.

Here's Tamino's graph of the two data points Solomon is comparing. The graph is of the anomaly of the sea-ice extent; which means it's a measure of how much the extent differs from the average extent for that time (I'm assuming, since I don't see pronounced seasonal periodicity).

Note too that Solomon, like Bast, is cherry picking a date in April for his comparison. A glance at the Arctic Sea Ice Monitor shows that sea ice extent varies very little at this period when the melting is just beginning. This is because things get covered with ice in the winter -- global warming isn't going to change that anytime soon.

The important question is what happens at the end of the melting season. And that's where we see the frightening drop in ice extent, and the prospect of facing an ice-free arctic some summer in the next couple decades.

No one is suggesting that ice won't still form in the winter; but that thin new ice is going to melt away in the summer, and that's going to lead to even more warming (because ice reflects heat, but open ocean absorbs it), and is going to lead to serious environmental problems for the arctic.

(Update 6/2/13: And here's Lawrence Solomon two months later still making the same argument. To be fair, we are into June now, so the extent is a bit more relevant. But do you think Solomon will be highlighting the extent in September, when it matters?)

Nov

1

It is natural to think that if a scientific theory (e.g., evolutionary biology or climate science) is indeed well-supported by evidence, then a public debate would be a great forum for the scientists to defend their views against creationists or climate-change deniers.

After all, isn't science all about presenting evidence and letting the people decide?

But in reality, science doesn't work that way.

1. Science is a deliberately slow and unamusing enterprise. What matters is long-term, careful, informed evaluation.

Debates are won using rhetoric and theatrics. Immediate, unreflective agreement is the goal.

2. Science evaluates claims based on the best evidence available.

Debates are won merely with the appearance of evidence.

3. Science needs to deal with counterarguments and contrary evidence.

In debates, one can pile up "evidence" for one side while ignoring all the evidence that undermines that side.

4. Science is difficult to explain and to understand. Years of study are often required.

Anti-science debaters do not need to get their audiences to understand difficult and subtle scientific points.

Following up on this last point, the deck is stacked in favor of the anti-science denialist for several reasons:

Then there's the fact that those debating on the denialist team are often experience showmen. They know how to entertain and persuade in a debate context. Scientists rarely have these skills, since they aren't taught or selected for in an academic context.

Even if there is a good pro-science debater, what will win the debate is usually not the science itself.

http://www.talkorigins.org/faqs/debating/globetrotters.html

Nov

1

"To suppose that the eye with all its inimitable contrivances for adjusting the focus to different distances, for admitting different amounts of light, and for the correction of spherical and chromatic aberration, could have been formed by natural selection, seems, I freely confess, absurd in the highest degree."

"To suppose that the eye with all its inimitable contrivances for adjusting the focus to different distances, for admitting different amounts of light, and for the correction of Spherical and chromatic aberration, could have been formed by natural selection, seems, I freely confess, absurd in the highest degree. When it was first said that the sun stood still and the world turned round, the common sense of mankind declared the doctrine false; but the old saying of Vox populi, vox Dei ["the voice of the people = the voice of God "], as every philosopher knows, cannot be trusted in science. Reason tells me, that if numerous gradations from a simple and imperfect eye to one complex and perfect can be shown to exist, each grade being useful to its possessor, as is certain the case; if further, the eye ever varies and the variations be inherited, as is likewise certainly the case; and if such variations should be useful to any animal under changing conditions of life, then the difficulty of believing that a perfect and complex eye could be formed by natural selection, should not be considered as subversive of the theory."

Darwin then went on to describe how some simple animals have only "aggregates of pigment-cells...without any nerves ... [which] serve only to distinguish light from darkness." Then, in animals a bit more complex, like "star-fish," there exist "small depressions in the layer of [light-sensitive cells] -- depressions which are "filled ... with transparent gelatinous matter and have a clear outer covering, "like the cornea in the higher animals." These eyes lack a lens, but the fact that the light sensitive pigment lies in a "depression" in the skin makes it possible for the animal to tell more precisely from what direction the light is coming. And the more cup-shaped the depression, the better it helps "focus" the image like a simple "box-camera" may do, even without a lens. Likewise in the human embryo, the eye is formed from a "sack-like fold in the skin."

George Gaylord Simpson in The Meaning of Evolution, points out that the different species of modern snail have every intermediate form of eye from a light-sensitive spot to a full lens-and-retina eye.

Creationist quotes geologist saying that "it appears these strata are out of order" and then omits the following line that explains that they were clearly pushed out of place (and when pressed, at, made the excuse that "one has to stop quoting somewhere")?

"Whitcomb and Morris do not quote that sentence. Perhaps this is because it conflicts with the point they are trying to defend. Or perhaps we should accept the explanation that Gish is reported to have offered at the Arkansas trial: 'After all, you have to stop quoting somewhere.'" (Kitcher 1982:182)

Here's a news story that includes the Romney ad: YouTube. (If you find the original ad up, send me the link and I'll post it.)

It should be obvious why quote mining is a dishonest fallacy. But here's a video that makes it clear:

When you quote mine, you can attribute anything to a speaker or author. It's a form of lying.

This is noteworthy because it's so egregious, but, of course, somewhat milder versions of this fallacy are commonplace in political "discourse," and sometimes some interpretation is required.

Mitt Romney: "Corporations are people, my friend." (He wasn't defending the Supreme Court's position that corporations are persons, he was claiming that any money that goes to corporations goes to people that make up -- or work for, or invest in -- the corporation. But this fits into his critics' claims that he is indifferent to workers and only cares about business owners.)

Obama: "You didn't build that." (He wasn't saying that owners didn't build their businesses, he was saying that they didn't build "roads and bridges" that allowed their businesses to thrive. But it fits into his critics' claim that he doesn't give sufficient credit and support to business owners and that he gives government too much credit.)