http://archives.bu.edu/web/elie-wiesel/videos/video?id=424828

Tag Archives: Lecture

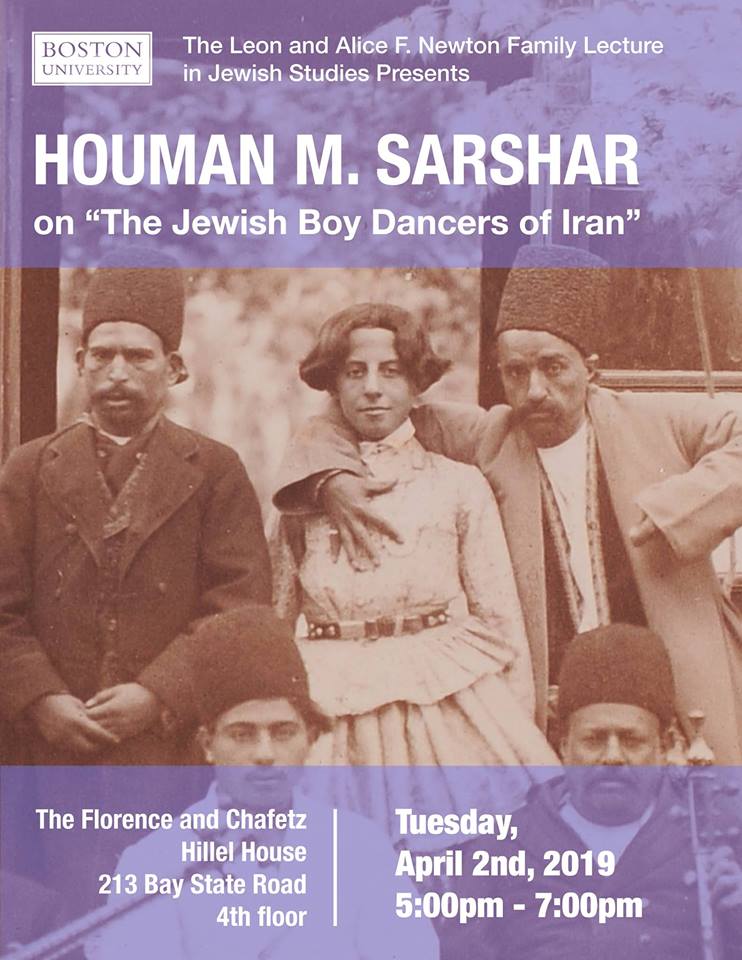

Where Did all the Dancers Go? Scholar Uncovers the World of Jewish Boy Dancers in Iran

By: Katherine Gianni

Dr. Houman Sarshar’s passion for promoting the art, culture, and history of Iran is well in evidence. It leaps off the pages of the books and articles he’s written, the volumes he’s co-edited, and it is embedded in the Kimia Foundation, an independent humanities organization that Dr. Sarshar founded and continues to oversee.

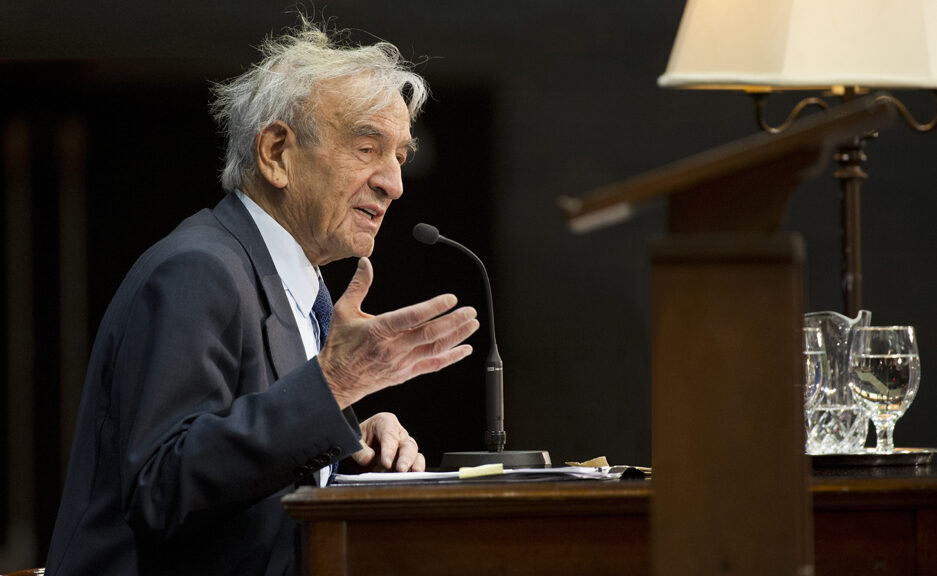

On Tuesday, April 2, Dr. Sarshar shared his zeal for the subject with the Boston University community in a lecture on The Jewish Boy Dancers of Iran. His presentation came as part of the Leon and Alice F. Newton Family Lecture in Jewish Studies, an event co-sponsored by The Elie Wiesel Center for Jewish Studies and the Boston University Center for the Humanities.

“Over the years, thanks to this series, we’ve been able to invite preeminent scholars in all areas of Jewish studies to BU,” said Associate Professor of Hebrew, German, and Comparative Literature Abigail Gillman in her welcoming remarks.

The lecture was established almost 30 years ago by the children of Leon and Alice F. Newton as a way to honor both their father, an alum of what was then called the BU School of Management, and their mother. Past speakers have included scholar Susannah Heschel, theologian Arthur Green, and philosopher Hilary Putnam, among others.

“Dr. Houman Sarshar did his undergraduate work in French and English literature at UCLA and his PhD in comparative literature at Columbia University. He’s a scholar, perhaps my favorite kind of scholar,” Associate Dean of the Faculty/Humanities Karl Kirchwey said, a grin spreading across his face. “One without a university affiliation.”

In his independent study of boy dancer entertainment in Iran, Dr. Sarshar has complied enough research to fill the pages of an entire encyclopedia. Through in-person interviews, thorough analysis of Qajar photography, and countless hours of fact-checking, he has laid the groundwork to learn more about the prevalence of such boy dancers in the past and their eventual disappearance from Iranian culture.

Prior to beginning his presentation, Dr. Sarshar issued a warning to the audience of students and community members gathered in the Florence and Chafetz Hillel House.

“The culture of dancing boy entertainment in Afghanistan has shed much necessary light on the despicable dynamics of enslavement, human trafficking, and sex slavery that today forms the backbone of this heart-wrenching hidden world,” he said. “While many of the features of the dancing boy entertainment of today’s Afghanistan are without doubt remnants of the same long tradition in neighboring Iran in particular, and the entire Persian world in general, there is at the very least one material distinction between what happens in twenty-first century Kabul and what occurred in pre-constitutional Iran. And that difference is time.”

Dr. Sarshar expressed that he was not referring to time in its chronological sense, but rather, “in the fullest sense of zeitgeist as the defining spirit or mood of a particular period of history as shown by the ideas and beliefs of the time.” By examining these dancers, he relayed that he did not wish to coat the realities of the boys’ humiliating position with a sense of nostalgia, but rather, use the images, texts, and testimonies as a means to broaden our understanding of the culture.

In telling the stories of the boy dancers, some of whom began their careers as early as six-years-old, Dr. Sarshar explained the ties between the profession and male homosexuality in Iran. While the dancers dressed in predominantly female clothing, he noted there was no mistaking the allure of their male gender identity. As various photographs and poems flashed across the screen, Dr. Sarshar argued that, despite legal strictures, Iranians widely engaged in homosexual relationships.

“Even occasional bans issued on male homosexual behavior throughout Iranian history had little impact on the love and desire of men over the years,” he said. “If anything, the fact that such bans had to be issued with any degree of frequency suggests that amorous and erotic relationships between men did not just occur in palaces, but throughout the general population.”

Dr. Sarshar concluded that the cultural norms surrounding homoeroticism, specifically when it came to dancing boy entertainment, shifted as Westerners categorized the practice as perverse, rather than something to be celebrated. The resulting shame led to the gradual disappearance of boy dancers. But, Dr. Sarshar, emphasized, there is still so much one can learn from this complicated history.

“The history of boy dancer entertainment in Iran is a rich one, not only in its scope and breadth, but more importantly in its unique capacity to provide a telescope with which to explore many dynamic nuances within Iranian society, culture, and even art history over the past 500 years,” Dr. Sarshar said. “My research therefore celebrates boy dancers and the culture of boy dancer entertainment precisely for the unprecedented analytic opportunities that the history of this tradition provides.”

To learn more about the Leon and Alice F. Newton Family Lecture in Jewish Studies visit https://www.bu.edu/jewishstudies/calendar/annual-lecture-series/.

The 2019 Yitzhak Rabin Memorial Lecture | US Jews and Israel: Are we headed for divorce?

Dear Friends of the Elie Wiesel Center:

The 2019 Yitzhak Rabin Memorial Lecture at Boston University, which will be held Thursday, April 11, is dedicated to an issue that is on the mind of many, namely, the culture of discourse, here in the US, on the issue of Israel and Palestine.

This culture of discourse, not the Israeli-Palestinian conflict as such, will be the focus of our event. Peter Beinart, our main speaker, believes–rightly, I think–that the current rise in the temperature of the debate here in the US, a debate that is perhaps not so much about Left and Right than it is about a difference between the generations, has more to do with developments in the American political and cultural landscape than with what is going on in Israel and across the Middle East. Today, the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, a foreign policy issue, provides a kind of lithmus test on who we are as Jews and Americans. This is the reason why we thought it might be time to have a conversation on Jewish Americans and the increasing polarization in how we think about Israel. For better or worse, Israel has become a touchstone in the American culture wars of the moment, or, as Mr. Beinart formulates, a proxy for American Jews to define themselves as Jews and as Americans.

I don’t believe that this is a very healthy situation, but it may be inevitable for Jews to think that way. It is inevitable because Jews cannot but be emotionally touched by Israel, a sovereign Jewish nation state founded by and for Jews, the first such state since biblical times.

Yet, how healthy can it be when American Jews feel compelled, or are expected, to define themselves, or be judged, by what goes on in a country of which they are not citizens, even if it is a Jewish nation state? And how healthy can it be for Israel when, what goes on in Israel for reasons grounded in the Israeli situation, becomes an echo chamber for a significant Jewish community in America, Israel’s most powerful ally, especially if that community is increasingly divided over Israeli politics and possibly frustrated with the entire Zionist project? Israeli attempts to influence American public opinion are legitimate, but charges of disloyalty, ethno-national betrayal, and Jewish self-hatred are not. Many young American Jews resent the lack of choice implied in these kinds of charges. Like other Americans they want to be able to decide for themselves what causes to support and what alliances to seek with others at home and abroad. They want to be able to decide whether or not they support Israel and for what reasons, precisely because they care and because their American Jewish identity is at stake.

This is a deeply emotional and divisive subject. A difficult conversation. But what better place than a university to try to model a difficult conversation across the political spectrum and give room to a variety of perspectives. Our goal is to move us out of the comfort zones of our respective “bubbles,” hear what moves others with whom we may disagree, and assume that people can disagree with one another without doubting one another’s good faith or humanity. This is called “dialogue.” It is also good political practice, a practice modeled for us by the ancient Athenians, as described by Hannah Arendt.

Impartiality (…) came into the world when Homer decided to sing the deeds of the Trojans no less than those of the Achaeans, and to praise the glory of Hector no less than the greatness of Achilles. This Homeric impartiality, as it is echoed by Herodotus, who set out to prevent “the great and wonderful actions of the Greeks and the barbarians from losing their due meed of glory,” is still the highest type of objectivity we know. Not only does it leave behind the common interest in one’s own side and one’s own people which, up to our own days, characterizes almost all national historiography, but it also discards the alternative of victory or defeat, which moderns have felt expresses the “objective” judgment of history itself, and does not permit it to interfere with what is judged to be worthy of immortalizing praise.

Somewhat later, and most magnificently expressed in Thucydides, there appears in Greek historiography still another powerful element that contributes to historical objectivity. It could come to fore ground only after long experience in polis-life, which to an incredibly large extent consisted of citizens talking with one another. In this incessant talk the Greeks discovered that the world we have in common is usually regarded from an infinite number of different standpoints, to which correspond the most diverse points of view. In a sheer inexhaustible flow of arguments, as the Sophists presented them to the citizenry of Athens, the Greek learned to exchange his own viewpoint, his own “opinion” – the way the world appeared and opened up to him (dokei moi, “it appears to me,” from which comes doxa, or “opinion”) – with those of his fellow citizens. Greeks learned to understand – not to understand one another as individual persons, but to look upon the same world from one another’s standpoint, to see the same in very different and frequently opposing aspects. The speeches in which Thucydides makes articulate the standpoints and interests of the warring parties are still a living testimony to the extraordinary degree of this objectivity.

(Hannah Arendt, Between Past and Future (1961), pp. 51-2.)

The academy is founded on the ideals of objectivity and impartiality, and it behooves us recall these ideals as we think about how we can move beyond the impasse of polarization. Let the other side be heard! Or, as the rabbis taught, the School of Hillel prevailed because it was in the habit of reporting not just the opinions of their own school but also the opinions of the opposing school.

I hope you will join us for “US Jews and Israel: Are we headed for divorce.”

Sincerely,

Michael Zank

Director, EWCJS