It probably wasn’t the comment Justice Stone thought of as his magnum opus, but a buried footnote to his opinion in a 1938 economic regulation case has spurred law review article titles such as Judicial Protection for Powerless Minorities and The Origins of Judicial Activism in the Protection of Minorities for suggesting that the Supreme Court might have good reason to question laws referencing or separating out social minorities. He wrote:

“…prejudice against discrete and insular minorities may be a special condition, which tends seriously to curtail the operation of those political processes ordinarily to be relied upon to protect minorities, and which may call for a correspondingly more searching judicial inquiry.”

A common understanding of this comment is that the political process informing new laws breaks down with prejudicially skewed distribution of institutional attention, and the Supreme Court can step in on behalf of those shafted by the break down when it reviews laws in dispute. For example, I’m guessing no racial minorities participated in the crafting of a VA law that averted “a mongrel breed of citizens” by banning racial minorities from intermarrying with Whites, though racial minorities presumably could intermarry amongst themselves with abandon. Here, institutional attention went toward to White supremacy, but the Supreme Court noticed and called it out.

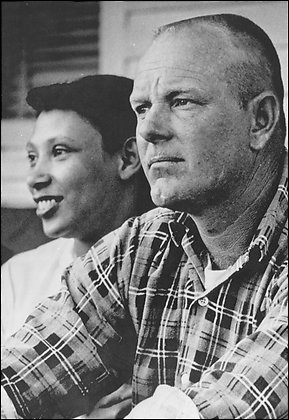

In 1967, Loving v. Virginia (what a case name!) debuted a Supreme Court willing to override such race-based legislation for not being necessary to a permissible government purpose—the law didn’t survive this early formulation of strict scrutiny. Thus, the intermarried Lovings could just be married instead of being felons guilty of “corruption of blood.” The ruling was ideologically traceable to Justice Stone’s famous footnote.

In 1967, Loving v. Virginia (what a case name!) debuted a Supreme Court willing to override such race-based legislation for not being necessary to a permissible government purpose—the law didn’t survive this early formulation of strict scrutiny. Thus, the intermarried Lovings could just be married instead of being felons guilty of “corruption of blood.” The ruling was ideologically traceable to Justice Stone’s famous footnote.

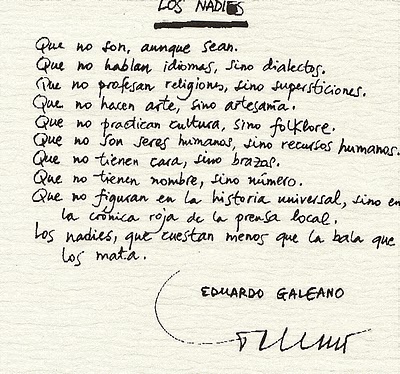

As a songwriter, I’ve tried to turn a few phrases in my day, chosen to go beyond carrying a tune to making a statement that might stick after the music stops. I’ve been charged by quotes from Dom Helder Camara’s “When I feed the poor, they call me a saint, but when I ask why the poor are hungry, they call me a communist” to Eduardo Galeano’s “Fleas dream of buying themselves a dog, and nobodies dream of escaping poverty…The nobodies: nobody’s children, owners of nothing…Who do not appear in the history of the world, but in the police blotter of the local paper.”

I’m now in a setting where words carry new weight—beyond a call to action, a lawyer’s words can frame decisions. Justices since Stone’s intimation of strict scrutiny have vied over what language should fine tune its application, from Justice Steven’s unfavored “govern impartially” to Justice Stewart’s up-and-coming “exceedingly persuasive justification.” Determining which terms are controlling—choosing to test for a “legitimate” or “important” or “compelling” government purpose—can make the difference between a law getting a thumbs up or down, meaning people on the ground live through different legal regimes based on…a few words. Here’s to finding the right words at the right time, even if by accident.

I’m now in a setting where words carry new weight—beyond a call to action, a lawyer’s words can frame decisions. Justices since Stone’s intimation of strict scrutiny have vied over what language should fine tune its application, from Justice Steven’s unfavored “govern impartially” to Justice Stewart’s up-and-coming “exceedingly persuasive justification.” Determining which terms are controlling—choosing to test for a “legitimate” or “important” or “compelling” government purpose—can make the difference between a law getting a thumbs up or down, meaning people on the ground live through different legal regimes based on…a few words. Here’s to finding the right words at the right time, even if by accident.

One Comment

Yaminette posted on April 2, 2010 at 3:16 pm

Yes, finding the right words at the right time…hopefully we can move beyond accidentality into saying things with purpose and letting those words turn into action. Great poem by Galeano and I enjoyed looking at the links, both new for me. I enjoyed reading your perspective.