Per Magnus, a student in the College of Communication, has written a profile of me for one of his classes. I share it with you as it will give you an idea of my background and the circumstances that brought me to the arts.

To pick a single high point in Benjamin Juárez’s career in the arts is like singling out the brightest star on a clear winter night; there are too many to choose from. Yet one is incandescent for its perseverance.

The funny thing is that he hadn’t even planned to do it. When the director of the Gran Festival de la Ciudad de Mexico called him on a Friday night in 1990, Juárez was as surprised as anyone to hear what he had to say: The conductor of the Kremlin ballet orchestra had vanished, possibly fleeing to the U.S. in hope of a better life. Their iconic Macbeth concert was scheduled for next Thursday. Was there any chance Juárez could step in and do the job?

Juárez, then the musical director of the festival, wasn’t sure. To take on a completely new conducting job five days before the premiere would be extremely hard, if not impossible. He thought about it for a moment. Then agreed to do it. Virtually every hour of the following weekend he spent studying. He was assigned a driver so that he could work while on to go. He listened to the musical score even while he ate. “Once I am in this mode I’m nonstop,” Juárez says.

On Monday he had taught himself the score, and started rehearsing with the 90-strong orchestra. On Thursday they premiered the ballet together in front of 1,800 people. In the end both Juárez and the festival director could breathe a sigh of relief; the performance was a success and Juárez was eventually invited to conduct in Moscow.

“I somehow saved the day. I’m very proud that I wouldn’t crack under pressure,” he says of the episode today.

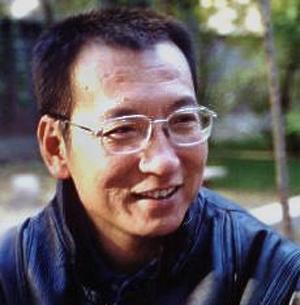

When Benjamin Juárez took office as dean of Boston University’s College of Fine Arts on August 1 this year, he carried a more humble approach. “I come here as a student,” he told BU Today. Such modesty was in stark contrast to the optimism that radiated from BU faculty following his appointment. They described the 59-year-old Mexican as a “remarkable man,” with a knowledge of the arts that was “international in scope.”

Benjamin Juárez has lived, studied, and worked in a handful of countries. He speaks five languages and has extensive leadership experience within the field of arts, among other things as director of Mexico’s national arts center.

But there’s also an unexpected side to BU’s latest dean. The calm eyes resting behind the square glasses combined with the gentle Mexican accent gives him an aura of a loving grandfather – not a digital enthusiast.

Yet, Benjamin Juárez has more than 1,000 friends on Facebook. His emails are more likely to be sent from an iPad or iPhone than from a computer. He has an iPod that will play you everything from Argentine rock bands to the Black Eyed Peas. And don’t be surprised if you find a post on his blog written at two in the morning about the connection between science and art, or about the flutist that discovered the stethoscope.

“Benjamin has a passion for learning new things, he is open to learning about everything and anything,” says his wife, Marisa Canales. “His curiosity is never-ending,” says one of his friends. “He has an intellectual curiosity, and is always talking about the latest book he’s read,” says another.

However, both Juárez and those who know him seem to agree on one thing. “Benjamin is first and foremost, I think, an orchestra conductor,” says Saul Bitran, a violinist who has been a close friend since 1977, when Juárez invited him to take part in a chamber orchestra he conducted.

Cast a glimpse at Benjamin Juárez’s roots and you will see few signs of a future world-class conductor. His father was a State of Mexico-based entrepreneur who owned his own drug store. His mother, a housewife, did her best to support her husband. Neither were professional artists.

But take a deeper look, and the picture starts making sense.

When Benjamin’s father grew up in rural Mexico in the 1920s and 1930s, music wasn’t the preferred entertainment. It was the only entertainment. Some people sang, some had an instrument, but everyone played some part in music. Even his aunt who could only write in capital letters knew several arias of La Traviata by heart.

It was a heritage he would not forget. Shortly after Benjamin was born on July 17, 1951, the Juárez family got a record player. And they didn’t mind their son using it, even though he admits he “ruined many records.”

“I spent hours and hours listening to music, mostly classical music. And when a guest came to the house I would not only offer them water or coffee but also ask them if they wanted to listen to some ballet, or to some opera, or some symphonic music.”

Benjamin’s mother did not practice music, but in the afternoons she would take her son to the theater, ballet or exhibitions. In the evenings Benjamin’s father would play him lullabies on his violin. Some nights the toddler would ask him to stop, other times he would simply pretend to have fallen asleep until he quit playing. But mostly he enjoyed his father’s evening repertoire.

“From the beginning, for me, music making was not an option but a fact of life,” he says. Juárez’ playing, however, didn’t start out so well. When he was six he began taking piano lessons with a neighbor, and he concedes his playing was “very bad.”

His teacher agreed, and as soon as the Juárez family bought their own piano, little Benjamin quit the lessons and started playing at home. When he was ten he started teaching himself to read and write music.

“When I turned 15 I started buying tons of records. Tons and tons and tons. It was opera, classical, symphonic, renaissance music,” he says. Juárez started taking his passion even more seriously, studying piano, voice, and his father’s trademark instrument, the violin. He also found time to study drama for several years.

After finishing his bachelor’s degree in Mexico in 1969, he headed north to study in the U.S. At California Institute of the Arts (CalArts) he expanded his horizons in film, dance, design, animation, and visual arts, before graduating in 1973 with a MFA in music.

It was at CalArts that Juárez got to stand on the podium for the first time. He started conducting the practices of a string ensemble, and found the experience so much fun that he decided to study conducting techniques more thoroughly.

When he later went to Madrid for more studies, he got offered the job as a conductor of a choir in at the university. Benjamin Juárez was now a paid conductor.

In his twenties he also nurtured his passion from another angle – through a camera lens. After having started a weekly Sunday radio show with two friends in high school and writing for several newspapers in his teens, 25-year-old Juárez was hired to host televised opera and symphonic music concerts.

But it was on the podium he really excelled. As his career picked up speed he got invited to perform at a world festival in Shanghai, making him the first Latin American ever to conduct an orchestra in China. He has conducted some of Mexico’s most prestigious orchestras, and twenty years ago he became the hero of the day for a Russian ballet orchestra.

Through his career – be it as a student, performer, or teacher – music has sent the Mexican conductor to many a faraway place. In addition to shorter trips to countries like China and Russia, he has spent years and months living in Italy, England, Los Angeles, New York, San Francisco, Salzburg, Madrid and Paris. “I feel at home in several places,” he concludes.

The musical heritage is undoubtedly a great part of Benjamin Juárez’s career, but it is not the whole story. His parents would teach more than just love of music.

“They taught me a set of values,” he explains. Although an only child the first eight years of his life, Benjamin didn’t live alone with his mother and father. Like many middle-class households at the time, the family employed and housed a nanny and a woman working in the kitchen.

“We would always treat the house helpers with respect. If there were five of us and there were three pieces of bread, they would always be given first,” Juárez says.

He learned that when you receive a privilege in your life it is not for your own benefit – rather you have a responsibility to share it and to multiply it for the rest of society. He learned persistence and work ethic from his father, who started a soda company at the age of ten, and was the first to arrive and the last to leave at the drug store he later owned, even though he had 60 employees.

The persistence gene came in handy when Juárez met his second wife. “He was very obviously interested in me – very!” says Marisa Canales of the time the two were introduced twenty-one years ago.

She was a flutist, he a well-known figure in the Mexican cultural life. He asked her to dinner. Believing he was still married, she said no. “Then he told me that he had been divorced for a while,” she reminisces. She reconsidered the invitation, and one year later they were married.

Now they have left their home country, and they don’t plan on returning anytime soon. They leave behind Canales’ classical music record company and Benjamin’s two grown sons from his first marriage. One of them is a designer, the other is a pianist.

With a sister who works in the government, a brother who is doctor, and a second brother taking working in the family business, Benjamin is the only one to pursue a career in the arts tradition handed down to him by his father. His mother, now 86, doesn’t always think that was such a good idea.

“She is very excited about my new job and, shall I say, proud. But she is also a bit worried about my work as an artist. Had I been a lawyer or a doctor I would have a more stable job.”

But as for now, the dean has more than enough to do. With assistants constantly chasing him to give updates on a bursting schedule, you would think the baton will collect dust in the years to come.

That, however, is not going to happen.

“Just last week in Moscow I was invited to conduct the orchestra of the Central School of Music of the famous Tchaikovsky Conservatory, and if my work load at CFA allows it, I will conduct again every 4 months or so. It would be indeed very hard to quit that part of my life.”

It’s a part of his life that accounts for many of the highlights in a starlit career. Looking back at it, what does Benjamin Juárez himself consider the high point?

“After a concert I had done once, this gentleman came up to me and asked if I could sign a program for his daughter. He explained that she had terminal cancer and couldn’t be there. But she had listened to the same concert on the radio the day before, and for a few hours, by listening to the concert she had forgot about her illness. That’s music – without it life would be poor. That experience made me remember the value of music.