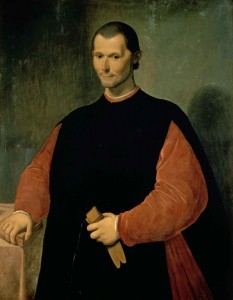

Portrait of Niccolo Machiavelli (1469-1527), Santi di Tito (1536-1603)/Palazzo Vecchio (Palazzo della Signoria) Florence, Italy/Bridgeman Art Library

Relating to CC201’s study of Niccolo Machiavelli’s the Prince, is an article discussing his ideas on whether law can supplant politics. Here is an extract:

One of the peculiarities of political thought at the present time is that it is fundamentally hostile to politics. Bismarck may have opined that laws are like sausages – it’s best not to inquire too closely into how they are made – but for many, the law has an austere authority that stands far above any grubby political compromise. In the view of most liberal thinkers today, basic liberties and equalities should be embedded in law, interpreted by judges and enforced as a matter of principle. A world in which little or nothing of importance is left to the contingencies of politics is the implicit ideal of the age.

The trouble is that politics can’t be swept to one side in this way. The law these liberals venerate isn’t a free-standing institution towering majestically above the chaos of human conflict. Instead – and this is where the Florentine diplomat and historian Niccolò Machiavelli (1469-1527) comes in – modern law is an artefact of state power. Probably nothing is more important for the protection of freedom than the independence of the judiciary from the executive; but this independence (which can never be complete) is possible only when the state is strong and secure. Western governments blunder around the world gibbering about human rights; but there can be no rights without the rule of law and no rule of law in a fractured or failed state, which is the usual result of westernsponsored regime change. In many cases geopolitical calculations may lie behind the decision to intervene; yet it is a fantasy about the nature of rights that is the public rationale, and there is every sign that our leaders take the fantasy for real. The grisly fiasco that has been staged in Afghanistan, Iraq and Libya – a larger and more dangerous version of which seems to be unfolding in Syria – testifies to the hold on western leaders of the delusion that law can supplant politics.

Machiavelli is commonly thought to be a realist, and up to a point it is an apt description. A victim of intrigue – after being falsely accused of conspiracy, he was arrested, tortured and exiled from Florence – he was not tempted by idealistic visions of human behaviour. He knew that fear was a more reliable guide to human action than sympathy or loyalty, and accepted that deception will always be part of politics.

That does not make Machiavelli a cynic, still less amoral…

For the full article, visit bit.ly/12NWSoJ.

One Trackback

[…] up on our previous posts, What Machiavelli Knew, Formichelli introducing Corgan on Machiavelli, and on a lighter note, Recipe for Bolognese […]