As February continues to barrage us with snow and ice, cold winds and cloudy skies, it can seem to many of us, especially those from warmer climes, that winter will never end, the snow will never melt, the days will never grow longer. At such a time, it can be nice to get a little perspective and think that, despite the cold and the damp and the gray, most of us will be spending these winter days inside where it’s warm (perhaps even too warm if you happen to be living in the overzealously heated dorms) and dry; we are all well fed and surrounded by hot chocolate and warm tea, and, oh yes, Hitler’s army isn’t laying siege to our walls.

Now many of us know more, already, than we want to about the harrowing 900 day siege that beset Leningrad in the early 1940’s. Death, despair, and famine all against the backdrop of Russia’s brutal weather and extreme winters. Russia has always been a country in opposition to the elements, carving cities out of ice it seems, even to those New Englanders who have been here in the chilly North winter after winter. It takes a tough breed to last those Russian winters, and this tough skin along with cold and hunger made them formidable foes to the Nazis, despite their own loss and suffering.

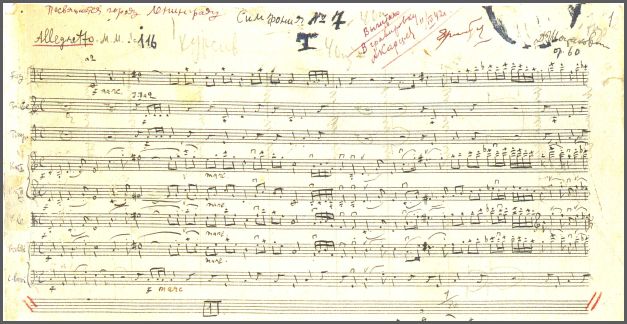

Of course many books, both fiction and nonfiction, have immortalized the story of Leningrad’s perseverance, but Brian Moynahan’s new book Leningrad: Siege and Symphony puts the siege in a different perspective by telling two tales simultaneously: the resistance against the Nazi’s and the creation and first Leningrad performance of Shostakovich’s Seventh Symphony, dedicated to the battered city and a symbol of opposition and the free world to the West in the days following the war. Yet, according to this review of the book by Stephen Walsh, even more moving than the symbol this symphony did and has become is the descriptions of the concert where music was created against unimaginable odds:

How else to explain the successful performance of the Seventh Symphony that following August? It was a full-blooded 70-minute work for an orchestra of more than 100, performed by a radio band reduced by death and infirmity to a mere handful of sickly regulars, augmented by military-band players from the battlefront and by whatever extra wind and string players could be drafted in from the city’s dilapidated musical substrata, and directed by a conductor — Karl Eliasberg — who could himself barely hold a baton or stand upright.

Even more moving is the realization of this concert:

Yet eventually, at the final rehearsal, it all suddenly comes together, and the performance is an incredible triumph, greeted by a packed Philharmonie with a standing ovation that begins even before the end of the work, as the players falter and the audience urges them on.

The human will is an amazing thing that can create beauty and music in such conditions. Every year, still, there is a performance of this over an hour long piece in the very same concert hall where the original performance happened. If you need more inspiration than that to get through the rest of winter, here it is, the complete symphony that inspired a city about to break.