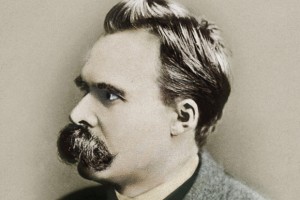

For several reasons, Philosophy departments in the United States have traditionally recommended a safe distance from Nietzsche.

One is the prose style, which shows a penchant less for analysis and more for Dionysus. Another is hygiene: the charge of anti-Semitism has stuck to him like a bad scent, despite the attempts by expositors, most notably Walter Kauffman, to scour his reputation. The latest attempt comes from Daniel Blues, in his detergent The Making of Friedrich Nietzsche, reviewed by Christopher Bray of The Spectator. Bray asks:

But does Blue offer as radically new a portrait of Nietzsche as he claims? On the whole, Im afraid, no. In essence, what this book does is translate into biographical terms the more analytical findings of Walter Kaufmann’s still groundbreaking studyNietzsche: Philosopher, Psychologist, Antichrist. Prior to the publication of that book in 1950, it was a critical commonplace that Nietzsche was a crazed Teutonic supremacist whose poetic ranting was of no philosophical worth. Kaufmann went back to the original texts to show how, far from being a proto-dictator, Nietzsche (who once called himself the lastanti-politicalGerman) was in fact a proto-existentialist a rationalist moralist who believed that the only thing worth conquering was the self.

But does Blue claim to offer a radically new portrait of Nietzsche? On the whole, I’m afraid, Bray does not quote Blue as telling us so. Where else does Blue go wrong?

Nietzsche isnt just the greatest stylist in the history of philosophy. Hes one of the greatest stylists in the history of the written word. As with Shakespeare, reading Nietzsche is like reading a dictionary of quotations: practically every line seems both familiar and startling.

Which means that the big drawback of Blues impressively researched book is its prose.

That is a familiar and startling leap. Cutting out the middleman may be cheap, but bad for ones argument. Does it follow that because Nietzsche writes glittering prose that Blue is obliged to use it as a standard for his own? I do not think he means to say so, but it does then impugn the “which means,” which means that it is not being used honorably but as a lubricant on which we must let the writer slip without doing so ourselves. Familiar and startling, these tactics: remember Petrarch, Rousseau, Montaigne…Nietzsche?