It is apt that a man whose life mission was incomplete should have biographers . devoted to making it seem more wholesome. A recent review by Benjamin Kunkel at The Nation .tells us that the latest such attempt, Marx’s Revenge .by Gareth Stedman Jones, tries to have us seeMarx as a relic of the nineteenth century.

Stedman Jones has something like the opposite purpose in mind: He portrays a Marx who, as a creature of the public

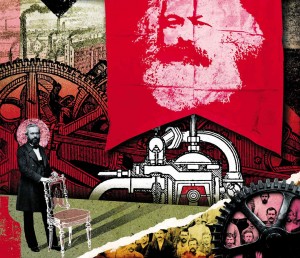

controversies and sectarian intrigues of his time, belongs to the past rather than the future, his thought a historical curiosity with little enduring explanatory power. Stedman Jones, a professor of history in England who was once a frequent contributor to the New Left Review but no longer identifies as a revolutionary socialist, dismisses the mythology surrounding Marx that had already begun to be constructed at the time of [his] death in 1883, especially in Germany and Russia. The mythology purveyed the image of a forbidding bearded patriarch and lawgiver, a thinker of merciless consistency with a commanding vision of the future. This was Marx as the twentieth century was-quite wrongly-to see him.

That is a major blow for those of us who are opening Das Kapital .to a random page forusing the first quote we see as oracular advice. But Jones does seem to be correct on the essential point–that much of the mythology not only surrounding but clouding and shrouding Marx is in need of being dispelled. One of the major ones that is still being purveyed as a fashionable trademark of American politics, left and right, is that the socialist experiment that went awry in the Soviet Union used Das Kapital, an unfinished work, as an instruction manual.

Read the full review at The Nation