Via Library of Congress.

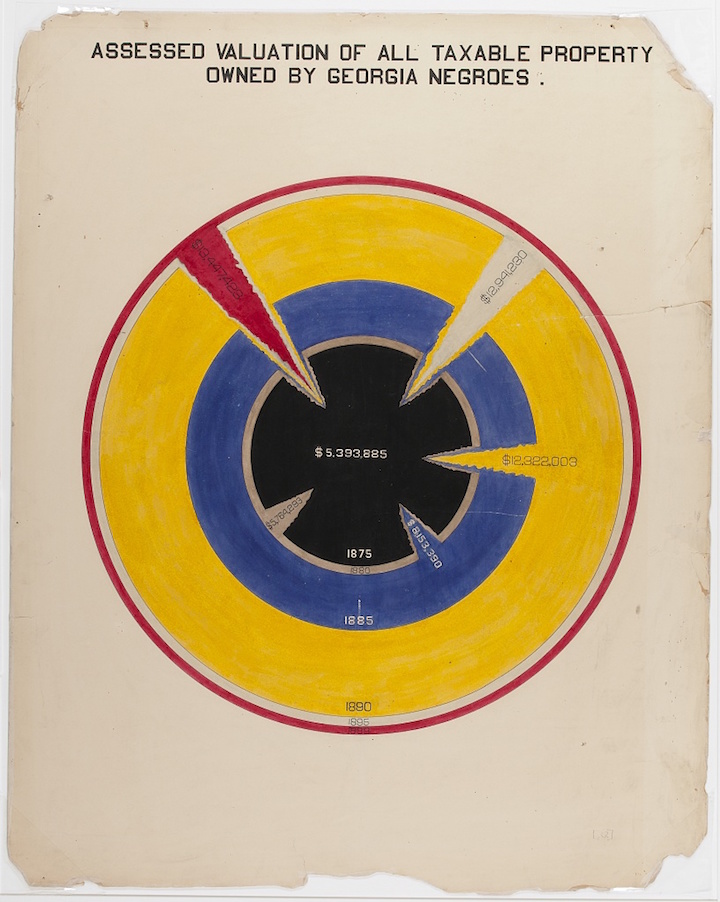

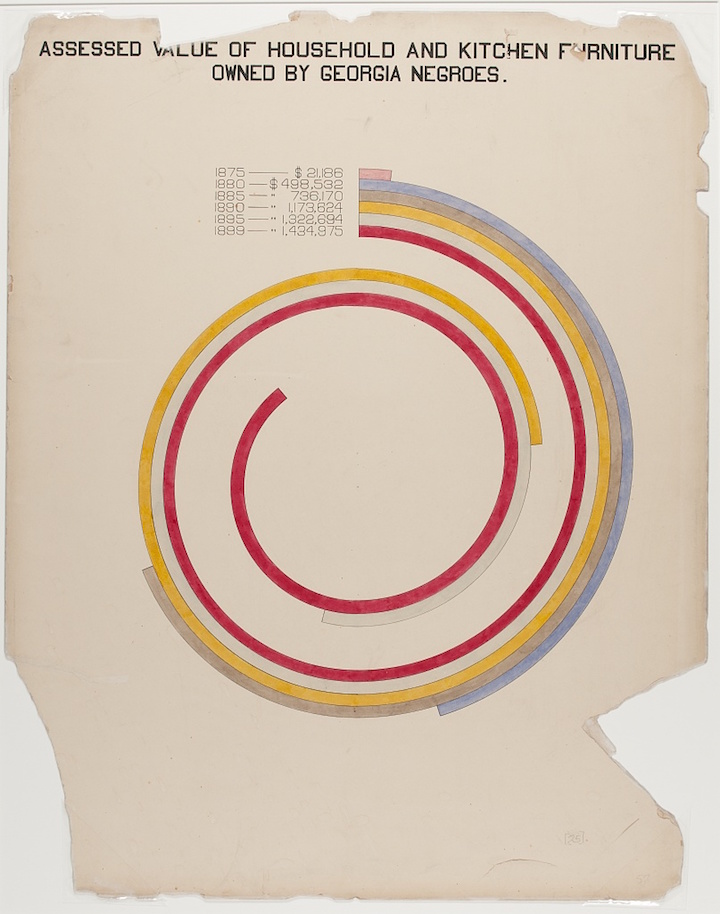

At the turn of the twentieth century, author, sociologist, and activist W.E.B. Du Bois traveled to Europe for the Paris Exposition alongside collaborators Thomas J. Calloway and Daniel Murray. There, numerous photographs, patents, books, and more would make up an exhibition entitled “The Exhibit of American Negroes,” which showcased African-American life. Among these glimpses of culture and achievement were 58 charts hand-drawn by the author and his students at Atlanta University in Georgia. (Sound familiar? You may recognize Du Bois’ infographics from Theaster Gates’s “But to Be a Poor Man,” an art show earlier this year.) These infographics, beautiful in their own right, condense various collections of data concerning African Americans in both the United States as a whole and in Georgia in particular. Thomas Calloway, who ran the exhibit, provided some insight into its purpose in a quotation noted by business reference specialist Ellen Terrell of the LOC:

It was decided in advance to try to show ten things concerning the negroes in America since their emancipation: (1) Something of the negros history; (2) education of the race; (3) effects of education upon illiteracy; (4) effects of education upon occupation; (5) effects of education upon property; (6) the negros mental development as shown by the books, high class pamphlets, newspapers, and other periodicals written or edited by members of the race; (7) his mechanical genius as shown by patents granted to American negroes; (8) business and industrial development in general; (9) what the negro is doing for himself though his own separate church organizations, particularly in the work of education; (10) a general sociological study of the racial conditions in the United States.

Via Library of Congress.

Despite the awards that the exhibit garnered those involved as well as the exposure to about 50 million people, the press in the United States, with the exception of African-American-based periodicals, ignored its success. Nonetheless, as is pointed out by the Public Domain Review, the exhibit was “very much a milestone in the fight for equal rights.” Du Bois, as we know, would have gone on to publish The Souls of Black Folk three years later, not to mention his championing of the cause for equal rights in the coming years.

Read more about the exhibit on the Public Domain Review and on Hyperallergic.